Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 3–4

December 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Enabling Team Resilience Against Calamities Through Sensemaking in Global Construction Engineering Projects

Sarath Gunathilaka

Department of Construction Management, School of Architecture, Design and the Built Environment, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Corresponding author: Sarath Gunathilaka, sarath_gunathilaka@yahoo.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9095

Article History: Received 31/03/2024; Revised 12/01/2025; Accepted 18/07/2025; Published 05/12/2025

Citation: Gunathilaka, S. 2025. Enabling Team Resilience Against Calamities Through Sensemaking in Global Construction Engineering Projects. Construction Economics and Building, 25:3/4, 163–185. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i3/4.9095

Abstract

The work teams in global construction engineering projects (GCEPs) tend to face various natural and man-made calamities that can catastrophically influence their performance; thus, enabling team resilience becomes vital. The literature shows noteworthy evidence identifying collective sensemaking as a key enabler to achieving team resilience, but this has still not been empirically confirmed and creates a knowledge gap. The global construction organizations also argue whether these teams actually need collective sensemaking for this purpose since team members will not have face-to-face interactions during times of calamities as they reside in different countries and work via virtual mode. With the results of a questionnaire survey among 52 GCEP teams, this paper concludes the positive and significant relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience, confirming that the teams need collective sensemaking to become resilient. This finding makes an original contribution to the theory and practice in the GCEP sector and highlights the importance of much-needed attention from these teams to create collective sensemaking to become resilient against calamities. A recommendation is made for revealing practical ways of achieving this in a future study.

Keywords

Collective Sensemaking; Global Construction Engineering Projects; Project Calamities; Project Teams; Team Resilience

Introduction

Enabling team resilience is vital for the teams in global construction engineering projects (GCEPs) because they face performance challenges from time to time due to calamities in their volatile project environments. Volatility is referred to as the difficulty in understanding the outcome of a complexity (Mack et al., 2016). The GCEP environment is always volatile due to many complexities and calamities such as climate change (Röser, 2024), terrorism (Aho and Lehtinen, 2024), economic fluctuations and political shifts (Alparslan, 2024), and rapid technological advancements (Alparslan, 2024; Röser, 2024). Such volatilities can disrupt the level of team performance, creating numerous risks (Röser, 2024). Among these volatilities, calamities become significant performance issues and challenges. A calamity is a serious accident or a bad event causing damage or suffering according to the online Cambridge Dictionary. For example, the recent COVID-19 pandemic was a calamity that created damage and suffering to all industries around the world (Nurizzati and Hartono, 2023). There are two categories of calamity as accepted by the United Nations (Green, 1993). The first category is natural calamities that are exogenous and non-human immediate causes, whereas the second category is man-made disasters such as war (Grenn, 1993). Some examples of natural calamities are blizzards (Cappucci, 2024; Halverson, 2024), cyclones (Forbis et al., 2024), earthquakes (Qiu et al., 2024; Zei et al., 2024), flood (Dharmarathne et al., 2024), hurricanes (Comola et al., 2024), landslides (Sharma et al., 2024; Svennevig et al., 2024), tornadoes (Forbis et al., 2024; Strader et al., 2024), tsunamis (Iwachido, Kaneko and Sasaki, 2024), volcanic eruptions (Bilbao et al., 2024; Lin and Su, 2024), and wildfires (Ferreira, Sotero and Relvas, 2024). Man-made calamities include disasters such as arson (Ribeiro et al., 2024), biological/chemical threat (Reddy, 2024), civil disorder (Braha, 2024), crime (Davies and Malik, 2024), cyber-attacks (Teichmann and Boticiu, 2024), terrorism (Kanwar and Sharma, 2024), and war (Wilson, 2024). Because a project environment can be volatile, GCEP teams can encounter both types of calamity that can influence their performance. Thus, they should have the ability to enable team resilience for the mitigation of risks regardless of calamities they encounter for them to operate smoothly within the expected level of performance (Júnior, Frederico and Costa, 2023).

Literature provides noteworthy evidence to identify collective sensemaking as an exclusive construct that can enable team resilience (e.g., Talat and Riaz, 2020). The meaning of collective sensemaking is the process of generating and evaluating a shared understanding among a group of people connected by a common environment, such as a construction project, in response to complex challenges like calamities. For example, when a calamity is identified across, a team should immediately detect the risk, and the message about the danger is to be communicated among all team members instantly. Generally, all team members in the GCEPs are not co-located and they work virtually and remotely, residing in different locations and countries. There are occasional remote and virtual-working situations for team members in any work team nowadays, but this situation is permanent in GCEP teams. Owing to their virtual team setup, these team members do not have face-to-face interactions in close proximity. Hence, making collective sense is practically difficult although this is needed for them to become resilient against calamities. Thus, there is a contemporary debate among global construction organizations over whether these teams actually need collective sensemaking to become resilient. This has still not been confirmed through research, and thus, creates a knowledge gap. There is no empirical evidence on deciding the relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in GCEP teams. In a recent study, Malla and Delhi (2022) highlighted the importance of identifying the crucial barriers in large infrastructure construction projects to interface best management practices. In most cases, GCEPs are large-scale infrastructure projects.

This paper aims to fill the knowledge gap by confirming the relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in GCEP settings through a quantitative study. The findings will help GCEP teams understand the importance of collective sensemaking to maintain performance resilience against calamities.

Literature review

Team resilience

As discussed in the Introduction, team resilience is needed for maintaining the existing level of team performance against calamities in a volatile business or project environment such as a GCEP (Hartmann et al., 2020). As team resilience is a key construct in this paper, it is important to derive its definition for the context of GCEPs. The teams in GCEPs face significant challenging situations to manage, for example, the recent calamity of COVID-19 pandemic. These challenging situations are called “perturbations” that are defined as the major external or internal spikes in the pressure beyond the normal range of variability (Gallopın, 2006). Therefore, withstanding or recovering from perturbations is part of team resilience. When the working situation in a project is changed and the performance is adversely affected beyond the normal level of control, the project teams need enabling resilience to reset the original or appropriate level of performance (Castka et al., 2001). Thus, setting back to the original or appropriate level of performance is part of team resilience. Anvuur (2008) viewed this as a quick recovery by lowering the sensitivity to shocks and stresses in the work environment. Alliger et al. (2015) defined team resilience as the capacity of a team to withstand and overcome stressors in a manner that could enable sustained performance. This asserts that team resilience helps the teams to handle and bounce back from challenges that can endanger their cohesiveness and performance. According to the view of Pavez et al. (2021), team resilience is the ability of a team to prosper despite adverse conditions such as high degrees of stress. Taken together, team resilience for the context of GCEPs is defined as the capacity of a team to withstand or recover from perturbations due to challenges and disasters such as shocks, pressure, stresses, and calamities by lowering their sensitivity to such occurrences and set back to the original or appropriate level of performance (Castka et al., 2001; Gallopın, 2006; Anvuur, 2008; Alliger et al., 2015; Pavez et al., 2021).

Literature shows that identifying the vulnerability of team members in the project environment is important before and when they become resilient teams (Ionescu et al., 2009; Alliger et al., 2015; Fisher, LeNoble and Vanhove, 2023). Being able to identify vulnerability in team members means being capable of keeping an eye on prevailing circumstances and being able to assess limitations that might affect performance (Alliger et al., 2015). Addressing vulnerabilities is important for the teams in GCEPs concerning both natural and man-made calamities, but most significant for resilience against natural calamities. Ionescu et al. (2009) highlighted the importance of accurate communication and elimination of misunderstanding to address vulnerabilities on natural calamities such as climate changes. Furthermore, Fisher, LeNoble and Vanhove (2023) viewed that the capacity to acknowledge vulnerability was needed for teams to become resilient. Moreover, Alliger et al. (2015) highlighted the importance of the application of “minimizing” strategy at the earliest stage to plan contingencies before the arrival of problems such as calamities for the project teams to become vulnerable. Another aspect that is needed for the project teams to become resilient is transformability (Alliger et al., 2015; Roy, 2022; Iao-Jörgensen, 2023). Transformability is the ability to recognize significant changes in one’s environment and respond to them successfully, often by creating a new system. It enables individuals, teams, companies, or societies to better cope with uncertainties by reshaping themselves in response to a changed environment. In GCEPs, transformability can help them become resilient, depending on prevailing circumstances. For example, Iao-Jörgensen (2023) highlighted the strategy of transformative resilience against external project disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The literature also shows that project teams need persistency to become resilient (Hamel and Valikangas, 2003; Alliger et al., 2015; Skalski et al., 2022). Generally, persistency refers to continuous attempts to manage challenging situations regardless of the prevailing strength of a team. This is needed for the teams in GCEPs to become resilient against both natural and man-made calamities. Persistency creates a positive association of mental resilience and well-being and, thus, this is helpful when dealing with calamities (Skalski et al., 2022). However, persistent thinking of team members does not always lead to team resilience, and it depends on the context of the calamity. For example, Skalski et al. (2022) argued that persistent thinking might be dysfunctional for mental health because it had inflated the anxiety and disrupted well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adaptability is also needed for the project teams to become resilient (Gallopin, 2006; Alliger et al., 2015; Prasetyo et al., 2022; Roy, 2022). Adaptability is applicable mostly toward achieving team resilience against man-made calamities that are encountered in GCEPs, but it depends on the nature of the calamities. For example, Roy (2022) viewed that adaptability to climate change would enable project resilience and, eventually, this idea could be extended toward team resilience due to the interchangeable nature of project and team contexts. Prasetyo et al. (2022) also empirically illustrated the positive relationship between adaptability and organizational resilience that could also be extended to team resilience due to the interchangeable nature of the two. The coping ability of team members is also an important aspect for them to achieve a resilient status (Groesbeck and Aken, 2001; Alliger et al., 2015). Coping ability is the strength of the teams to withstand project changes in a way that does not allow the creation of adverse performance issues. Groesbeck and Aken (2001) illustrated the aspect of strong team wellness for coping with changes to become resilient in team settings. Chai and Park (2022) highlighted the strategy of virtual and remote working to maintain team wellness and coping ability during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to this analysis, the variables of vulnerability, transformability, persistency, adaptability, and coping ability should be considered in developing team resilience.

Collective sensemaking

The concept and theory development relating to collective sensemaking were initiated at the end of the 20th century (e.g., Weick, 1993). However, this has been an evolving research theme over the last three decades (e.g., Bitencourt and Bonotto, 2010; Klein, Wiggins and Dominguez, 2010; Bietti, Tilston and Bangerter, 2019; Pham et al., 2023; Knight et al., 2024). As defined in the literature, collective sensemaking is the assignment of meanings to issues or events that cause the current state of the world to become different from the expected (Cristofaro, 2022). For example, when a calamity occurs in a GCEP, the entire team needs to make sense of its occurrence in advance or instantly in order to take precautions for it not to influence team performance. Some authors viewed collective sensemaking an intangible human characteristic (e.g., Klein, Wiggins and Dominguez, 2010). This is the reason for the difficulty in understanding and measuring collective sensemaking in team settings. Prior researchers in this area stated that sensemaking was an individual cognitive activity that was influenced by the position of an individual in a social system on the individual perspectives (e.g., Maitlis, Vogus and Lawrence, 2013; Zhang and Soergel, 2014). However, collective sensemaking in team settings is difficult to accomplish and more critical because it poses team coordination requirements that can easily break down (Klein, Wiggins and Dominguez, 2010). Generally, collective sensemaking in the team environment is a process created in the mind of every individual (Bitencourt and Bonotto, 2010). This is the reason for the difficulty in creating collective sensemaking in team settings when calamities are encountered in the GCEPs because team members are virtually dispersed across different locations and countries.

As collective sensemaking is also a key construct in this paper, it is necessary to establish its definition for the context of GCEP. Some authors identified collective sensemaking as a goal-oriented collective activity (e.g., Stensaker, Falkenberg and Grønhaug, 2008; Bietti, Tilston and Bangerter, 2019). Some other authors argued that collective sensemaking is made with the contribution of all individuals in a team by influencing each other (e.g., Weick, 1993; Frohm, 2002; Boreham, 2004; Gray, 2007). However, collective sensemaking is not an aggregation of individual sensemaking because if team members make individual sense of a prevailing situation, the team-role structure will be disintegrated and the ability to make sense will be lost (Frohm, 2002). According to Klein, Wiggins and Dominguez (2010), collective sensemaking is a macro-cognitive and collective team function that helps to understand the current situation and anticipate the future against uncertain and ambiguous conditions. Further research evidence shows that collective sensemaking does not always happen through every team member contribution; rather, it is the team’s capacity to integrate and build up shared mental models to create collective knowledge (Akgün et al., 2012). Further evidence indicates that communication, reflection, and social cognition are the elements of collective sensemaking to create such mental models (Talat and Riaz, 2020), and these are to be made at a particular point in time and space (Varanasi et al., 2023). The teams should have analytical capacity, synthesizing and interpreting the situation to share appropriate narratives to build up such social cognition to make sense collectively (Neill, McKee and Rose, 2007; Klein, Wiggins and Dominguez, 2010; Akgün et al., 2012). Taken together, collective sensemaking is defined as a goal-oriented ongoing process in a team that involves exchanging of provisional understanding or connecting of cues and trying to agree on consensual interpretations through information gathering and re-interpretation of narratives and/or a course of analytical actions that are developed through shared mental models for creating knowledge to identify what is going to occur at a particular point in time and space (Weick, 1993; Frohm, 2002; Boreham, 2004; Gray, 2007; Neill, McKee and Rose, 2007; Stensaker, Falkenberg and Grønhaug, 2008; Klein, Wiggins and Dominguez, 2010; Akgün et al., 2012; Bietti, Tilston and Bangerter, 2019; Talat and Riaz, 2020; Varanasi et al., 2023).

There is a view that collective sensemaking is needed for the teams to become resilient against calamities. Managing calamities appropriately is very important for the teams in GCEP settings and, thus, whether collective sensemaking can enable team resilience against calamities in such a virtual team setting is worth investigating. The rest of this paper focuses on exploring the relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in GCEP team settings.

Hypothesis

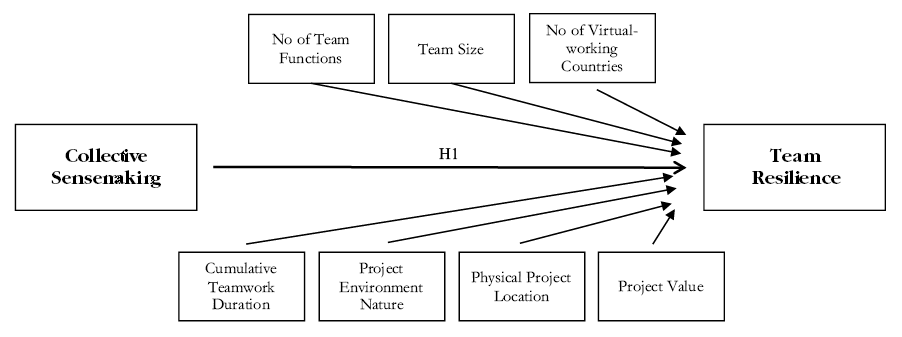

Literature shows noteworthy evidence to postulate the hypothesized relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in Figure 1 for the teams in GCEPs. For example, Boreham (2004) stated that collective sensemaking was needed for identifying and resolving problematic situations or events in a workplace. The workplace in the context of this paper is a GCEP. Applying the view of this author to the GCEP context, it can be stated that a team in a GCEP needs collective sensemaking to identify problematic situations or events such as calamities that they come across in their projects. Identifying problematic situations is the vulnerability reviewed earlier in this paper as part of team resilience (Ionescu et al., 2009; Alliger et al., 2015; Fisher, LeNoble and Vanhove, 2023). This means that collective sensemaking is needed for the teams in GECPs to become resilient. Then, they can show resilience by taking immediate actions to prevent the influence of such problems or adverse events and come back to the normal or appropriate level of performance (Castka et al., 2001). For the teams in GCEPs, making sense in this manner is very important due to the turbulent nature of the volatile global project environment that can cause simultaneous calamities. The literature shows evidence of disasters due to the failure of making collective sense to become resilient in team settings such as the Mann Gulch disaster reviewed by Weick (1993). This disaster happened due to the team’s failure to engage in collective sensemaking to become resilient in order to avoid the disaster. This analysis provides compelling evidence to predict the positive relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in GCEP team settings. In a recent study, Varanasi et al. (2023) also supported the positive relationship of collective sensemaking to team resilience during calamities such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this finding is not related to the GCEP sector, this view can be extended. Murphy and Devine (2023) also confirmed that sensemaking could help in adapting to the situations of crisis and changes such as the COVID-19 pandemic in a primary school environment. Although the focused environment by these authors is different from the GCEP environment, applying this finding to predict the positive and significant relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in GCEP team settings is valid in the same context. Moreover, Talat and Riaz (2020) also confirmed the direct impact of team sensemaking on team resilience for the work teams in the information and communication technology projects that can also be extended to the GCEPs, as above. Thus, for the GCEP team settings, the following can be expected.

Figure 1. Conceptual research framework

H1: Collective sensemaking will positively and significantly influence team resilience.

This paper tests this hypothesis using the primary data collected from the teams in GCEP settings through a quantitative questionnaire survey. The next section describes the research design and methodology adopted to test this hypothesis.

Method

Research design

The research design of a study depends on the research questions (Bryman, 2015; Bryman and Bell 2015; Saunders et al., 2016). The research study related to this paper investigated the research question of what the relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience is in the GCEPs. To answer this question, H1 is postulated with the help of the literature as shown in the conceptual research framework in Figure 1. The questions about the assumptions made for developing this conceptual research framework by the researcher regarding how GCEP teams work illustrate the ontological philosophical position of the research (Saunders et al., 2016). As the scope of the study was investigating the hypothesized relationship in the GCEP context, literature alone was insufficient due to limited available sources. Thus, a quantitative research approach was more appropriate to test the hypothesis (Creswell, 2014; Saunders et al., 2016). This means that, epistemologically, this study was of the belief that complex interactions among the various team members in GCEPs could be explored through a systematic and simplified approach adopting positivist perspectives of the acceptable knowledge on the GCEP teams that is constituted through direct observable variables that can be quantifiable (Bryman, 2015; Bryman and Bell, 2015). Hence, a questionnaire survey among team members in GCEPs was adopted. As the conceptual research framework was at the team level, only team-level data were necessary to test the hypothesis. Therefore, the respondents were asked to provide team-level data on the basis that the individuals were nested in teams and, thus, they could provide team-level information.

Measures

The first step of the questionnaire survey was developing the survey instrument. Generally, if the survey instruments are available in the literature, researchers will not need to develop new instruments. Accordingly, the existing survey instruments were used with slight minor modifications of the texts to suit with the GCEP context. Each item scale in the survey instruments utilized a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) in a way that matched with the data analyzing strategy discussed below. Extra care was taken to select item scales that had known and validated psychometric properties to minimize the risk of selecting incompatible survey instruments and to ensure that the research was free from bias. For this purpose, existing item scales were checked in terms of three theoretical methods used in quantitative research (Field, 2009). Data for applying these validity tests were taken from the results of papers that the item scales were adapted from as well as subsequent studies that the item scales were used. In the first method, the item scales with loading factors below 0.5 were reduced using the available exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results in the literature. Second, the item scales in components were reduced using the basis of composite reliability or Cronbach’s alpha below 0.7. In the third method, the group of items with negligible percentage of loading compared to the total item scale were reduced as this is a common method used in quantitative research.

Collective sensemaking was measured with the 31-item scale of Akgün et al. (2012). The original study was on team sensemaking and, thus, the survey instrument aligned with the context of the study. The item scale represents six dimensions with valid psychometric properties: internal communication (α = 0.84), external communication (α = 0.77), information gathering (α = 0.84), information classification (α = 0.89), building shared mental models (α = 0.89), and experimental action (α = 0.92). None of the items could be deduced according to the three methods described above using existing data analysis results in literature and, thus, all 31 items were used. Akgün et al. (2012) adapted seven-item scales for internal communication from Neill, McKee and Rose (2007) and Park, Lim and Philip (2009); four-item scales for external communication from Chang and Cho (2008); five-item scales for information gathering from Moorman (1995); five-item scales for information classification from Akgün et al. (2006); five-item scales for building shared mental models from Lynn, Reilly and Akgün (2000); and experimental action through five-item scales from Bogner and Barr (2000).

Team resilience was measured adapting the 40-item scales developed by Alliger et al. (2015) in their conceptual literature review paper. This survey instrument was matched with the context of team resilience in this paper. However, there was no evidence of data analysis results of this survey instrument in the literature and, thus, there was no psychometric evidence to reduce the item scales. Therefore, all 40-item scales were used for the survey.

Sample selection

After developing the questionnaire, the sample population was decided on. The survey was conducted among team members in GCEPs, and the teams were selected from anywhere in the world through international contacts, networking, and also with the input received from a few professional bodies and global collaborative organizations. Data were collected from randomly selected individuals in each team following the method of simple random sampling. A key contact person was appointed for each agreed participant team to select random respondents and to coordinate the communications. The first criterion for the sample selection was geographical dispersion of team members in two or more countries in order to make sure that the data were collected from global virtual teams. Generally, such global teams may have a combination of team members from different organizations. Therefore, in order to acquire a specific sample, selection was limited to the teams with team members from a single organization as the second criterion. No restrictions were imposed in terms of the nature, the sector, and the value of the projects as well as the functions and sizes of the teams because the research question does not depend on these factors.

The adopted data analyzing strategy consists of several methods as discussed in the next section and the sample size was decided accordingly because this is very important in quantitative research. The minimum threshold limit was set as 150 responses for the EFA (Field, 2009) and 50 teams for the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis (Maas and Hox, 2005). Satisfaction of the sample size for the Spearman correlation test was also checked using the equation given by Bonett and Wright (2000).

Data analyzing strategy

The data analyzing strategy consists of applying analyses in two stages. The first stage is the data preparation and the second stage tests H1. The purpose of carrying out the data analysis in two stages is to acquire strong and validated results for making research conclusions. The first step in the first stage of data analysis was conducting missing data analysis. This was conducted both manually and with the IBM SPSS software.

The second step in stage 1 was conducting the EFA. This analysis examines the underlying patterns and relationships for a large number of variables in a dataset and determines whether the information can be condensed or summarized in a smaller set of factors or components (Field, 2009). Although existing survey instruments in the literature have been used, the purpose of applying the EFA was to test the suitability of item scales for the GCEP context and also for the item reduction by examining the dimensionality and reliability of all measures. This test was performed with the help of IBM SPSS software using principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation. The PCA is a multivariate data analyzing technique that is used to extract important information from a large data table. This is carried out by means of a smaller set of new orthogonal variables called principal components that displays the pattern of similarity of observations and variables as points in maps (Abdi and Williams, 2010). This is a versatile statistical technique that can be used to reduce cases-by-variables in a data table into principal components (Greenacre et al., 2022). To apply PCA with appropriate rotation, most researchers employ factor loading using the Varimax rotation to adjust the components in a way that makes the loadings either high positive, negative, or zero while components are kept uncorrelated or orthogonal (Corner, 2009). Similarly, the PCA with Varimax rotation was selected as the appropriate method for this study. Statistical validation of the results was tested with the thresholds of the 0.5 Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (Field, 2009; Napitupulu, Kadar and Jati, 2017) and composite reliability of 0.7 Cronbach’s alpha. The PCA seeks to explain the total variance including specific and error variance in the correlation matrix. The communality in a factor matrix is referred to as the sum of the squared loadings for a particular item that indicates the proportion of variance for the given item that is explained by the factors (Tavakol and Wetzel, 2020). Communalities provide information on how much variance that the variables have in common or share, and sometimes indicate how highly predictable variables are form from one another (Pruzek, 2005). If the communality value is higher, the more the extracted factors will explain the variance of the item (Tavakol and Wetzel, 2020). Generally, most studies use either 0.3 or 0.4 but, due to the relatively small sample size, only the communalities that were greater than 0.5 were selected (Field, 2009).

The data aggregation test was conducted as the third step because team-level (higher level) data were collected from a few individuals selected from each team (lower level) as no directly available indices to measure the higher-level variables (LeBreton, Moeller and Wittmer, 2023). The purpose was to check whether the results represent the team level without deviations outside the accepted ranges. The precondition for the aggregation test is that the group mean provides an adequate representation of the individual values (Cohen et al., 2001). For the aggregation test, the Within Group Agreement Index of rWG(J) developed by James et al. (1984) was applied. The rule-of-thumb applied was that the values of these indices were greater than 0.70 for sufficient homogeneity to warrant aggregation (cf. Harvey and Hollander, 2004). In order to further test the validity of the data, bivariate correlations among the team-level variables were also tested as the fourth step in data preparation. The threshold range of 0.3 to 0.9 was adopted to decide the validity (Field, 2009).

Thereafter, the second stage of data analysis to test H1 was performed. Both OLS regression analysis (parametric test) and Spearman correlation analysis (non-parametric test) were performed because two methods could give strong results in terms of methodological triangulation. As the survey variables were measured on a Likert scale, their normalities were checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and a diagnostic check was also conducted as part of applying the OLS regression analysis.

The first method applied to test H1 was OLS regression analysis. Regression is a way of predicting an outcome variable (dependent variable) from one or several predictor variables (independent variables) in a relationship (Field, 2009). The relationship in H1 is a simple regression because it has only one predictor variable as well as one outcome variable (Field, 2009) as shown in Figure 1. The survey instrument includes seven team-level control variables relating to the demographic information of the responding teams and their working environment in GCEPs (see Figure 1). These variables represent the complexity and the nature of the work environment in GCEPs. Although there were no direct influences identified in the literature, these control variables were included in the analysis due to their possible confounding effects on the hypothesized relationship. This predictor model is fitted with data in the regression and the method of least square is used to establish the line that best describes the data collected; the regression coefficient is its gradient (Field, 2009). The regression coefficient is used to assess the relationship where zero means no relationship whereas a positive or negative relationship depends on the positive or negative regression coefficient (Field, 2009; Hair et al., 2010). The method of predictor selection is crucial in the regression analysis. The most common methods used in research are the hierarchical, forced entry, and stepwise methods in either forward or backward ways. As the relationship in H1 was at the single level, a combination of the hierarchical and forced-entry methods was employed. The control variables were forced-entered (en bloc) as the first step and then the second step involved forced entry of the predictor variable with the control variables (en bloc) to determine its independent effects on the outcome variable. In OLS regression analyses, assumptions are made to determine the regression model fit as well as generalizing to a specific population (Field, 2009). Accordingly, this study made four assumptions suggested by Hair et al. (2010). They were the linearity of the phenomenon measured, homoscedasticity, independence of the error terms, and normality of the error term distribution. To assess the violation of the assumptions, researchers carry out some diagnostic checks to test how well or badly the regression model fits with the data (Field, 2009). As suggested by Hair et al. (2010), this study ran several diagnostic checks. The first was the plot of the residuals that represents the difference between the predicted and observed values for the outcome variable. The second was the scatter plot. These plots could be used to assess the violation of the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity. The third diagnostic test was the Durbin–Watson test to test the correlation between errors; the test statistics could vary between 0 and 4, with a value of 2 meaning that the residuals were uncorrelated (Field, 2009). The fourth diagnostic test was the histogram plot of the residuals that were visually checked for normal distribution (Hair et al., 2010) because the data were collected using a five-point Likert scale. Moreover, the F-ratio is the ratio of the average variability in the data that a given model can use to explain the average variability unexplained by the same model, and a good model should have an F-ratio greater than at least 1 (Field, 2009). This rule was adopted as the fifth diagnostic test to assess the fit of the model considered to test the hypothesis. If all diagnostic checks are satisfactory, the goodness of the fit of the regression model will be ascertained.

The second method applied for testing H1 was Spearman correlation analysis. This is a non-parametric test commonly used in quantitative research and a distribution free test that does not require assumptions about the underlying population or the distribution of data. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient determines a simple linear relationship between two variables and measures without dimensions (Al-Hameed, 2022).

Results

Survey respondents

The survey was conducted among team members in GCEPs, and a total of 165 responses were received from 64 teams. However, the final sample after completing data preparation and validation checks (discussed below) included 163 respondents for the EFA and 52 teams for the OLS regression and Spearman correlation analyses. The final sample consisted of 79% males and 21% females; 87% in the age range of 30–60 years; 94% with the education of a degree or above; 33% from the UK, 18% from Europe, and 33% from Asian countries; 84% at managerial level or above; 78% with more than 5 years of global project experience; and 56% from projects over USD 50 million.

Stage 1 data analysis

As the first step in Stage 1 for data preparation, missing data analysis was conducted. Initially, the responses were checked manually and one response was dropped due to missing some key information. Thereafter, the Missing Value Analysis option in SPSS was conducted (cf. Hair et al., 2010). The purpose was to determine whether the remaining pattern of missing data after deleting the cases was missing completely at random (MCAR). It was confirmed that the missing data pattern was MCAR because Little’s overall test of missing data was not significant (Little’s MCAR test: chi-square = 8,351.938, DF = 9,296, Sig. = 1.000). The remaining sample after these data preparation actions was 163 responses.

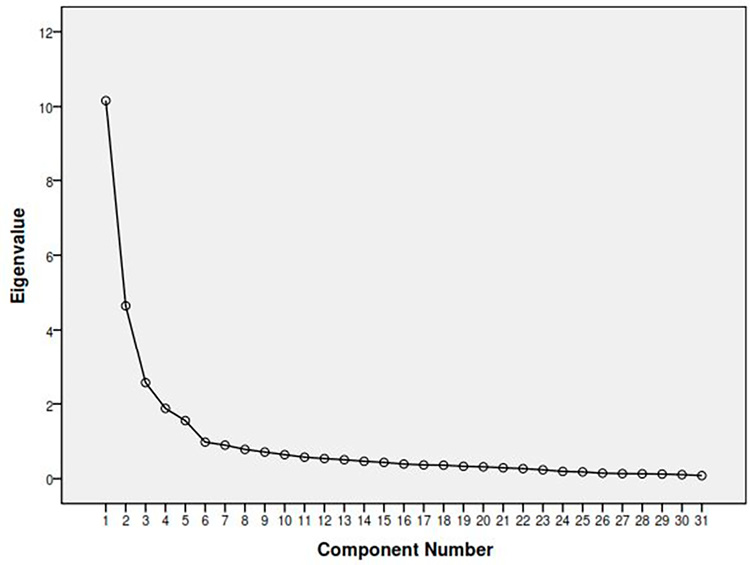

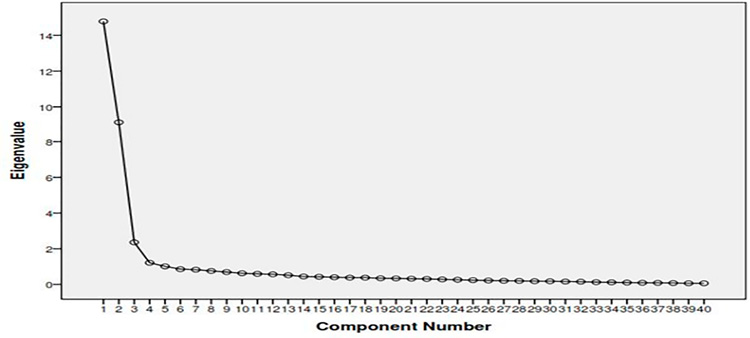

Thereafter, the EFA was conducted using PCA with Varimax rotation in the IBM SPSS software. The KMO measures of sampling adequacy for collective sensemaking and team resilience were 0.882 and 0.911, respectively, and, thus, the selected sample fulfilled the threshold of 0.5 (Field, 2009). Scree plots that show the fulfilled results of PCA for both collective sensemaking and team resilience are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. All item scales were loaded meaningfully and the variables/items that had not been loaded properly were dropped. The communalities of EFA results are shown in Tables 1 and 2 for collective sensemaking and team resilience, respectively. The final survey instruments used for testing H1 after dropping items according to threshold limits mentioned in the data analyzing strategy consisted of 19- and 36-item scales for collective sensemaking and team resilience, respectively; they show strong Cronbach’s alphas that are greater than the threshold limit of 0.7 (see Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 2. PCA scree plot of collective sensemaking

Figure 3. PCA scree plot of team resilience

Next, the aggregation test was conducted. The results indicated that both mean and median of team-level rWG(J) for the full sample were above 0.8 and satisfied the validation threshold limit of 0.7 (cf. Harvey and Hollander, 2004). However, responses from one team were dropped during this analysis because the results did not fulfill the validation check. In order to test the validity of data further, bivariate correlations among the team-level variables were also tested. None of the correlations among the variables was outside the adopted threshold range of 0.3 to 0.9 (Field, 2009). Overall, data from the sample fulfilled the requirement for testing the hypothesis.

Stage 2 data analysis

The first method applied to test the hypothesis in stage 2 was the OLS regression analysis in the IBM SPSS software. Before conducting the OLS regression, the normality was checked. Although the dependent variable was measured as non-parametric using a Likert scale, its normality check using the Shapiro–Wilk test had shown that the construct was normal, giving a p-value of 0.239 (>0.05). The construct was measured using an item scale of 40, and the calculated mean values with two decimal places were used for the analysis; thus, the normality check was fulfilled.

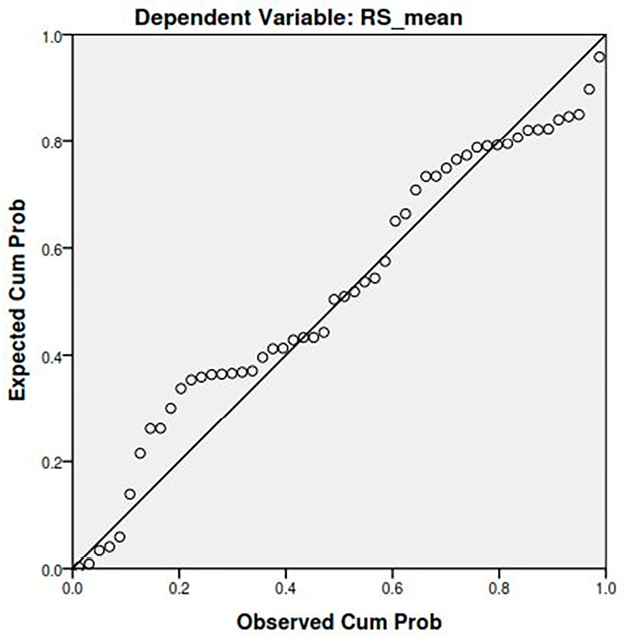

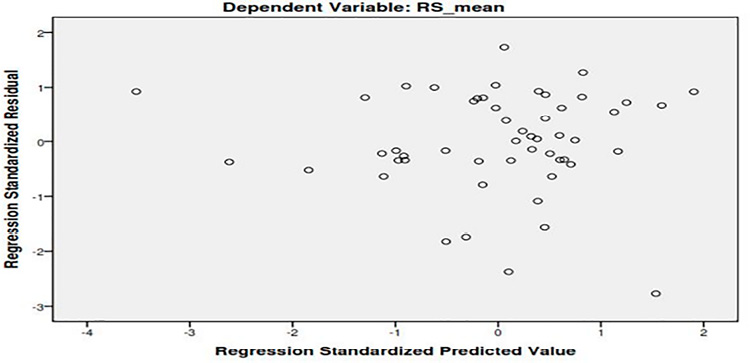

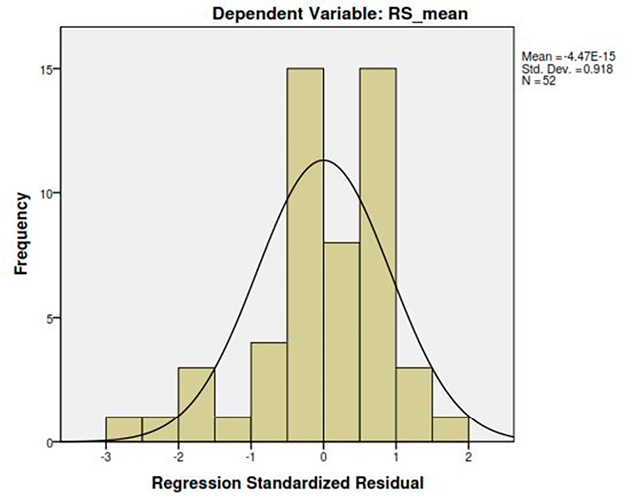

Thereafter, the OLS regression analysis in SPSS was performed. All control variables (en bloc) were run at the beginning (Model 1; Table 3). None of the control variables indicated either significant positive or negative relationships with team resilience (see Table 3). However, a reasonable positive relationship was shown between cumulative teamwork duration and team resilience (β = 0.21, p < 0.1), but it was not significant. Thereafter, at the second step, collective sensemaking and all control variables (en bloc) were run together (Model 2; Table 3). A positive and significant relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience was found (β = 0.59, p < 0.01). As diagnostic checks, Figures 4 and 5 show the satisfactory residual plot and the scatter plot. They were used to assess the violation of the assumptions relating to linearity and homoscedasticity. The Durbin–Watson test that was used to test the correlation between errors was also satisfactory, showing the value of 2.52 that is between the accepted levels of 0 to 4 (Field, 2009). Although the normality check was carried out before running OLS regression, the histogram plot was also checked (see Figure 6) and the normal distribution was re-confirmed (cf. Hair et al., 2010). The average variability check F-ratio had also shown a satisfactory result of 3.64 that was greater than the minimum threshold of 1 (Field, 2009). The regression coefficient and all diagnostic checks are satisfactory; thus, H1 is supported. The second test, Spearman correlation analysis, also supported this hypothesis, giving a positive and significant relationship at the 0.01 level (two-tailed), resulting in a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of 0.561 at <0.001 significance (two-tailed), as shown in Table 4. Thus, H1 is confirmed empirically.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; and †p < 0.10

Figure 4. Residual plot of regression analysis

Figure 5. Scatter plot of regression analysis

Figure 6. Histogram of team resilience

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Discussion of findings

The main finding in this study is the confirmation of the hypothesized relationship (H1) between collective sensemaking and team resilience for the GCEP team context, giving credibility to the authors who provided noteworthy evidence in the literature to postulate this hypothesis (e.g., Weick, 1993; Castka, et al. 2001; Boreham, 2004; Ionescu et al., 2009; Alliger et al., 2015; Talat and Riaz, 2020; Fisher, LeNoble and Vanhove, 2023; Murphy and Devine, 2023; Varanasi et al., 2023). This means that team resilience can be enabled through collective sensemaking in GCEP team settings regardless of whether team members are virtually dispersed across different locations and countries so that they do not have face-to-face interactions. This confirms that collective sensemaking is needed for them to know what is going on in their project environment and to take preventive or corrective actions immediately when they face or are going to face problematic situations such as calamities. The findings highlight the importance of creating collective sensemaking in GCEP settings to know what is going on to become vulnerable and resilient against calamities in order to prevent disasters like the Mann Gulch event described by Weick (1993).

The findings also confirm two survey instruments for the GCEP context. Collective sensemaking was confirmed with 19-item scales giving credibility to the authors who initially developed the survey instrument (Moorman, 1995; Bogner and Barr, 2000; Lynn, Reilly and Akgün, 2000; Akgün et al., 2006; Neill, McKee and Rose, 2007; Chang and Cho 2008; Park, Lim and Philip, 2009; Akgün et al., 2012). Similarly, acknowledging the original contribution of Alliger et al. (2015), the team resilience was confirmed with 36-item scales. Confirming these item scales will be helpful not only for future researchers to use in their studies but also for the teams in GCEPs to understand the important aspects to prioritize in their projects. Because of the volatile nature in the GECPs, knowing these aspects is helpful for them to apply appropriate preventive or corrective team-performance practices to face these challenges. For example, they may be able to use an integrated software to communicate instant warning messages on calamities to all virtually dispersed team members. However, revealing how these teams create collective sensemaking to manage calamities is not within the scope of this paper, and this is to be explored in a future study.

Conclusions

This paper concluded the positive and significant relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in the GCEP team settings, and achieved the aim and the objective. This conclusion was made empirically confirming H1 that was postulated drawing from the literature. This conclusion confirms that the teams in GCEP settings need to create collective sensemaking to enable team resilience against calamities regardless of the fact that team members work virtually and remotely, residing in different locations and countries without having face-to-face interactions. This conclusion was extended by confirming the survey instruments of collective sensemaking and team resilience with 19- and 36-item scales, respectively, for the GCEP context. This may help these teams to identify what aspects are to be prioritized for becoming resilient through collective sensemaking, but revealing these practices has not been addressed in this paper.

Concluding this relationship represents a significant contribution because the findings provide several crucial implications to the GCEP sector. Although a holistic approach focusing on every construct to enable team resilience in this context was not the focus of this paper, the empirically validated and confirmed relationship highlights an important aspect to be focused on (i.e., collective sensemaking). This finding provides clear evidence and much needed clarity on the importance of applying best practice in creating collective sensemaking in these project settings to become resilient against calamities. This is important because these team members work permanently in virtual team settings.

The originality of this finding is noteworthy and is one of the first research attempts to confirm the relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in GCEP team setting. This finding is a significant theoretical contribution as well as an original contribution to the body of knowledge in the construction management research domain; therefore, evidence for the confirmed relationship is no longer anecdotal. This paper also contributes to the knowledge in terms of methodological standpoint through the identification and validation of two item scales for measuring collective sensemaking and team resilience in GCEP team settings. Future studies can employ these survey instruments. This paper, thus, advocates coherent theories in the construction management research domain.

This research had two limitations. The first was due to the difficulty in the sampling of GCEPs because no information was available in a single place. Therefore, extra care was taken to distribute the survey among teams in GECPs across the world, although teams were found with the help of international contacts, professional bodies, and global collaborative organizations. The second limitation was the scope of this paper, which only revealed the relationship between collective sensemaking and team resilience in the GCEP team settings. Therefore, a recommendation is made to reveal how collective sensemaking is created to become resilient against calamities in the GCEP team settings in a future study.

References

Abdi, H. and Williams, L.J. 2010. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 2(4), pp.433-459. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.101

Aho, A.M. and Lehtinen, S. 2024. Global professionals in the turbulent world: a multi-case study on self-initiated expatriates in the interconnected external environment.

Akgün, A.E., Keskin, H., Lynn, G. and Dogan, D. 2012. Antecedents and consequences of team sensemaking capability in product development projects. R&D Management, 42(5), pp.473-493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2012.00696.x

Akgün, A.E., Lynn, G.S., and Yılmaz, C. 2006. Learning process in new product development teams and effects on product success. Industrial Marketing Management, 35, pp.210-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.02.005

Al-Hameed, K.A.A. 2022. Spearman’s correlation coefficient in statistical analysis. International Journal of Nonlinear Analysis and Applications, 13(1), pp.3249-3255.

Alliger, G.M., Cerasoli, C.P., Tannenbaum, S.I. and Vessey, W.B. 2015. Team resilience. Organizational Dynamics, 44, pp.176-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.05.003

Alparslan, F.F. 2024. Adapting strategies and operations: how Mnes navigate a volatile international business environment. Available at SSRN 4851180. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4851180

Anvuur, A.M. 2008. Cooperation in construction projects, PhD Thesis, The University of Hong Kong.

Bietti, L.M., Tilston, O. and Bangerter, A. 2019. Storytelling as adaptive collective sensemaking. Topics in Cognitive Science, 11(4), pp.710-732. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12358

Bilbao, R., Ortega, P., Swingedouw, D., Hermanson, L., Athanasiadis, P., Eade, R., Devilliers, M., Doblas-Reyes, F., Dunstone, N., Ho, A.C. and Merryfield, W. 2024. Impact of volcanic eruptions on CMIP6 decadal predictions: a multi-model analysis. Earth System Dynamics, 15(2), pp.501-525. https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-15-501-2024

Bitencourt, C.C. and Bonotto, F. 2010. The emergence of collective competence in a Brazilian Petrochemical Company. Management Revue, 21(2), pp.174-192. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2010-2-174

Bogner, W.C. and Barr, P.S. 2000. Making sense in hypercompetitive environments. Organization Science, 11(2), pp.212-226. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.2.212.12511

Bonett, D.G. and Wright, T.A. 2000. Sample size requirements for estimating Pearson, Kendall and Spearman correlations. Psychometrika, 65, pp.23-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294183

Boreham, N. 2004. A theory of collective competence: challenging the neo‐liberal individualisation of performance at work. British Journal of Educational Studies, 52(1), pp.5-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2004.00251.x

Braha, D. 2024. Phase transitions of civil unrest across countries and time. npj Complexity, 1(1), p.1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44260-024-00001-3

Bryman, A. 2015. Social research methods. Oxford University Press, UK.

Bryman, A. and Bell, E. 2015. Business research methods. Oxford University Press, UK.

Cappucci, M. 2024. New storm to bring blizzard and more tornadoes: city-by-city forecasts. The Washington Post.

Castka, P., Bamber, C., Sharp, J. and Belohoubek, P. 2001. Factors affecting successful implementation of high performance teams. Team Performance Management, 7(7/8), pp.123-134. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527590110411037

Chai, D.S. and Park, S. 2022. The increased use of virtual teams during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Resource Development International, 25(2), pp.199-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2047250

Chang, D.R. and Cho, H. 2008. Organizational memory influences new product success, Journal of Business Research, 61 (1), pp.13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.05.005

Cohen, A., Doveh, E. and Eick, U. 2001. Statistical properties of the rWG(J) index of agreement, Psychological Methods, 6 (3), pp.297-310. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.6.3.297

Corner, S. 2009. Choosing the right type of rotation in PCA and EFA. JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter, 13(3), pp.20-25.

Comola, F., Märtl, B., Paul, H., Bruns, C. and Sapelza, K. 2024. Impacts of global warming on hurricane-driven insurance losses in the United States. https://doi.org/10.31223/X5GQ4H

Cristofaro, M. 2022. Organizational sensemaking: a systematic review and a co-evolutionary model, European Management Journal, 40(3), pp.393-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2021.07.003

Davies, J. and Malik, H. 2024. The organisation of crime and harm in the construction industry. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003167990

Dharmarathne, G., Waduge, A.O., Bogahawaththa, M., Rathnayake, U. and Meddage, D.P.P. 2024. Adapting cities to the surge: a comprehensive review of climate-induced urban flooding. Results in Engineering, p.102123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102123

Ferreira, V., Sotero, L. and Relvas, A.P. 2024. Facing the heat: a descriptive review of the literature on family and community resilience amidst wildfires and climate change. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 16(1), pp.53-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12551

Field, A. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 3rd ed. Sage publications.

Fisher, D.M., LeNoble, C.A. and Vanhove, A.J. 2023. An integrated perspective on individual and team resilience. Applied Psychology, 72(3), pp.1043-1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12419

Forbis, D.C., Patricola, C.M., Bercos-Hickey, E. and Gallus Jr, W.A. 2024. Mid-century climate change impacts on tornado-producing tropical cyclones. Weather and Climate Extremes, 44, p.100684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2024.100684

Frohm, C. 2002. Collective competence in an interdisciplinary project context, PhD Thesis. Linköpings University. Sweden.

Gallopın, G.C. 2006. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), pp.293-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004

Gray, S.L. 2007. A grounded theory study of the phenomenon of collective competence in distributed, interdependent virtual teams, PhD Thesis, University of Phoenix, USA.

Greenacre, M., Groenen, P.J., Hastie, T., d’Enza, A.I., Markos, A. and Tuzhilina, E. 2022. Principal component analysis. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2(1), p.100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00184-w

Green, R.H. 1993. Calamities and catastrophes: Extending the UN response. Third World Quarterly, 14(1), pp.31-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436599308420312

Groesbeck, R. and Van Aken, E.M. 2001. Enabling team wellness: monitoring and maintaining teams after start‐up. Team Performance Management: An International Journal. 7(1/2), pp.11-20. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527590110389556

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. Pearson. New Jersey.

Halverson, J.B. 2024. An introduction to severe storms and hazardous weather. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003344988

Hamel, G. and Välikangas, L. 2003. The quest for resilience. Harvard Business Review, 81(9), pp.52-63.

Hartmann, S., Weiss, M., Newman, A. and Hoegl, M. 2020. Resilience in the workplace: a multilevel review and synthesis, Applied psychology, 69(3), pp.913-959. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12191

Harvey, R.J. and Hollander, E. 2004. Benchmarking rWG interrater agreement indices: let’s drop the .70 rule-of-thumb, paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago. https://doi.org/10.1037/e518632013-233

Iao-Jörgensen, J. 2023. Antecedents to bounce forward: a case study tracing the resilience of inter-organisational projects in the face of disruptions. International Journal of Project Management, 41(2), p.102440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2023.102440

Ionescu, C., Klein, R.J.T., Hinkel, J., Kavi Kumar, K.S. and Klein, R. 2009. Towards a formal framework of vulnerability to climate change. Environmental Modelling and Assessment, 14(1), pp.1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-008-9179-x

Iwachido, Y., Kaneko, M. and Sasaki, T. 2024. Mixed coastal forests are less vulnerable to tsunami impacts than monoculture forests. Natural Hazards, 120(2), pp.1101-1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06248-8

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G. and Wolf, G. 1984. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without bias, Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), pp.85-98 https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.69.1.85

Júnior, L.C.R., Frederico, G.F. and Costa, M.L.N. 2023. Maturity and resilience in supply chains: a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 5(1), pp.1-25. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIEOM-08-2022-0035

Kanwar, S. and Sharma, P.K. 2024. Overall construction safety and terror management. In AIP Conference Proceedings, 2986(1), AIP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0195565

Klein, G., Wiggins, S. and Dominguez, C.O. 2010. Team sensemaking. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomic Science, 11(4), pp.304-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639221003729177

Knight, E., Lok, J., Jarzabkowski, P. and Wenzel, M. 2024. Sensing the room: the role of atmosphere in collective sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2021.1389

LeBreton, J.M., Moeller, A.N. and Wittmer, J.L. 2023. Data aggregation in multilevel research: best practice recommendations and tools for moving forward, Journal of Business and Psychology, 38(2), pp.239-258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09853-9

Lin, E.R. and Su, S. 2024. Causal inference and machine learning in climate studies. Predicting Carbon Emissions and Assessing, 7th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ICAIBD), pp.17-20. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAIBD62003.2024.10604636

Lynn, G.S., Reilly, R.R. and Akgün, A.E. 2000. Knowledge management in new product teams. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 47(2), pp.221-231. https://doi.org/10.1109/17.846789

Maas, C. J. and Hox, J. J. 2005. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modelling. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 1(3), p.86. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241.1.3.86

Mack, O., Khare, A., Krämer, A. and Burgartz, T. (Eds.) 2016. Managing in a VUCA world, Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16889-0

Maitlis, S., Vogus, T.J. and Lawrence, T.B. 2013. Sensemaking and emotion in organizations. Organizational Psychology Review, 3(3), pp.222-247. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386613489062

Malla, V., & Delhi, V. S. K. 2022. Determining Interconnectedness of Barriers to Interface Management in Large Construction Projects. Construction Economics and Building, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v22i2.7936

Moorman, C. 1995. Organizational market information processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 32, pp.318-335. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379503200307

Murphy, G. and Devine, D. 2023. Sensemaking in and for times of crisis and change: Irish primary school principals and the Covid-19 pandemic. School Leadership & Management, pp.1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2022.2164267

Napitupulu, D., Kadar, J.A. and Jati, R.K. 2017. Validity testing of technology acceptance model based on factor analysis approach. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 5(3), pp.697-704. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v5.i3.pp697-704

Neill, S., McKee, D. and Rose, G.M. 2007. Developing the organization’s sensemaking capability. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(6), pp.731-744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2006.05.008

Nurizzati, A. and Hartono, B. 2023. Team resilience of construction projects: a theoretical framework. In AIP conference proceedings, AIP Publishing LLC, 2654(1). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0118964

Park, M.H., Lim, J.V. and Philip, H.B. 2009. The effect of multi-knowledge individuals on performance in cross-functional new product development teams. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26, pp.86-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2009.00336.x

Pavez, I., Gómez, H., Laulié, L. and González, V.A. 2021. Project team resilience: the effect of group potency and interpersonal trust. International Journal of Project Management, 39(6), pp.697-708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2021.06.004

Pham, C.H., Nguyen, T.V., Bach, T.N., Le, C.Q. and Nguyen, H.V. 2023. Collective sensemaking within institutions: Control of the COVID‐19 epidemic in Vietnam. Public Administration and Development, 43(2), pp.150-162. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1996

Prasetyo, A., Mursitama, T.N., Simatupang, B. and Furinto, A. 2022. Enhancing mega project resilience through capability development in Indonesia. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies, 14(3), pp.1-21.

Pruzek, R. 2005. Factor analysis: exploratory. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013192.bsa211

Qiu, H., Su, L., Tang, B., Yang, D., Ullah, M., Zhu, Y. and Kamp, U. 2024. The effect of location and geometric properties of landslides caused by rainstorms and earthquakes. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 49(7), pp.2067-2079. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5816

Reddy, D.S. 2024. Progress and challenges in developing medical countermeasures for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threat agents. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 388(2), pp.260-267. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.123.002040

Ribeiro, R., Teles, D., Proença, L., Almeida, I. and Soeiro, C. 2024. A typology of rural arsonists: characterising patterns of criminal behaviour. Psychology, Crime & Law, pp.1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2025.2564365

Röser, M. 2024. More certainty in uncertainty: a special life-cycle approach for management decisions in volatile markets. Journal of Management Control, pp.1-33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-023-00364-z

Roy, S. 2022. Integrating resilience through adaptability and transformability. In Resilient and Responsible Smart Cities, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2, pp.31-41. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86499-6_3

Saunders, M.N., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. 2016. Research methods for business students, 7th ed. Pearson Education, Harlaw, England.

Sharma, A., Sajjad, H., Roshani and Rahaman, M.H. 2024. A systematic review for assessing the impact of climate change on landslides: research gaps and directions for future research. Spatial Information Research, 32(2), pp.165-185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-023-00551-z

Skalski, S.B., Konaszewski, K., Büssing, A. and Surzykiewicz, J. 2022. Resilience and mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, p.810274. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.810274

Stensaker, I., Falkenberg, J. and Grønhaug, K. 2008. Implementation activities and organizational sensemaking. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(2), pp.162-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886307313794

Strader, S.M., Gensini, V.A., Ashley, W.S. and Wagner, A.N. 2024. Changes in tornado risk and societal vulnerability leading to greater tornado impact potential. npj Natural Hazards, 1(1), p.20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-024-00019-6

Svennevig, K., Koch, J., Keiding, M. and Luetzenburg, G. 2024. Assessing the impact of climate change on landslides near Vejle, Denmark, using public data. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 24(6), pp.1897-1911. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-24-1897-2024

Talat, A. and Riaz, Z. 2020. An integrated model of team resilience: exploring the roles of team sensemaking, team bricolage and task interdependence. Personnel Review, 49(9), pp.2007-2033. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2018-0029

Tavakol, M. and Wetzel, A. 2020. Factor Analysis: a means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. International Journal of Medical Education, 11, p.245. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5f96.0f4a

Teichmann, F.M. and Boticiu, S.R. 2024. Adequate responses to cyber-attacks. International Cybersecurity Law Review, 5(2), pp.337-345. https://doi.org/10.1365/s43439-024-00116-2

Varanasi, U.S., Leinonen, T., Sawhney, N., Tikka, M. and Ahsanullah, R. 2023. Collaborative sensemaking in crisis, In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, pp.2537-2550. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596093

Weick, K.E. 1993. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: the Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, pp.628-652. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393339

Wilson, A. 2024. Ukraine at war: baseline identity and social construction. Nations and Nationalism, 30(1), pp.8-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12986

Zei, C., Tarabusi, G., Ciuccarelli, C., Burrato, P., Sgattoni, G., Taccone, R.C. and Mariotti, D. 2024. CFTI landslides, Italian database of historical earthquake-induced landslides. Scientific Data, 11(1), p.834. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03692-4

Zhang, P. and Soergel, D. 2014. Towards a comprehensive model of the cognitive process and mechanisms of individual sensemaking. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(9), pp.1733-1756. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23125