Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 1

March 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Interacting Possibilities Between Building Information Modelling and Off-Site Manufacturing for Performance Improvement

Pejman Sabet1,*, Emil Jonescu2, Heap-yih Chong3, Chamil Erik Ramanyaka4

1 Civil Construction Department, Acknowledge Education, Melbourne, Australia, Pejman.Sabet@ae.edu.au

2 Research and Development, Hames Sharley, Perth, Australia, e.jonescu@hamessharley.com.au

3 School of Design and Built Environment, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, heap-yih.chong@curtin.edu.au

4 School of Engineering and Technology, Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, Australia c.ramanayaka@cqu.edu.au

Corresponding author: Pejman Sabet, Civil Construction Department, Acknowledge Education, Melbourne, Australia, Pejman.Sabet@ae.edu.au

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i1.8928

Article History: Received 25/11/2023; Revised 04/03/2024; Accepted 22/08/2024; Published 31/03/2025

Citation: Sabet, P., Jonescu, E., Chong, H-Y., Ramanyaka, C. E. 2025. Interacting Possibilities Between Building Information Modelling and Off-Site Manufacturing for Performance Improvement. Construction Economics and Building, 25:1, 221–243. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i1.8928

Abstract

Many studies have examined building information modelling (BIM) and off-site manufacturing (OSM) as separate concepts, yet few have examined their applications in a hybrid approach. To fill this literature gap, this study investigates the innovative simultaneous interactions of BIM and OSM in the Australian construction industry. Another aspect motivating this study is that the application of this novel approach in the global construction industry environment is considered equally crucial for advancing research in this sector. Covariance-based structural equation modelling was applied to investigate complex relationships between dependent and independent variables. For this empirical study, 105 academic publications were reviewed to build a solid foundation for achieving the research aims. The findings show that OSM and BIM are not widely used in Australia. Individually, these capabilities have had no considerable impact on the overall project performance, but BIM and OSM have constructively interacted when applied concurrently. The study concludes that the systematic implementation of BIM–OSM interactions could improve key productivity indicators, and subsequently, overall project performance. This BIM–OSM hybrid approach that aligns with the diffusion of innovation theory is best implemented at the planning and managerial stages to ensure a practical project operating system in OSM-based projects supported by BIM.

Keywords

Hybrid Approach; Project Performance; Diffusion of Innovation; Interaction

Introduction

The continued demand for increased construction productivity has prompted management to investigate consistent approaches for achieving this goal. Consequently, the emergence of advanced approaches has provided construction industry authorities with opportunities to mitigate the productivity decline in this sector (Dolage and Chan, 2013). Many companies have found that inefficient information flows between project parties adversely affect project performance at both the design and construction stages. However, modern construction techniques may be used to remedy problematic systems to improve construction productivity (Rathnayake and Middleton, 2023). Further, improved monitoring and control measures over project progress are additional considerations that promise increased productivity on dynamic construction sites (Kenley, 2014). In addition, off-site manufacturing (OSM) has been identified as a potential technique for upgrading the construction industry (Oti-Sarpong, et al., 2022). The OSM approach was created to improve efficiency in the built environment (Ziwen, Bon-Gang and Minghan, 2023) by optimising resource usage, safety and quality control and accelerating project progress. Notably, fragmented stakeholders, design inefficiencies, and inconsistent details about prefabricated components have been flagged as the root causes of poor productivity in OSM-based projects (Shahpari, et al., 2020).

In this regard, the quality of communication between a project’s stakeholders is critical to its success (Hosseini, Maghrebi, et al., 2016). Constructive collaboration originates from the presence of a forum for reliable information sharing and the ongoing capacity to view the project status via building information modelling (BIM) (Hosseini, Maghrebi, et al., 2018). Therefore, BIM has been highlighted as a reinforcer for OSM in addressing issues. While neither of these techniques has been able to satisfy all performance criteria in isolation, when used concurrently, a variety of interactions between them can accomplish the aims of both approaches (Lee, J. and Kim, 2017). This hybrid BIM–OSM technique requires a hybrid team capable of recognising and practising any constructive opportunities (BIM–OSM interactions) from such integration that is intended to resolve various productivity-related challenges in construction. A hybrid team consists of the planner, designer, contractor and manufacturer as project stakeholders in a building project (Hosseini, Banihashemi, et al., 2018). Sabet and Chong (2019) discussed that both BIM and OSM have been highlighted as groundbreaking methodologies that can tackle challenges to construction productivity.

However, the adoption of OSM and BIM differs across geographies. In particular, Gelic, Neimann and Wallwork (2016) noted the slow adoption of BIM in Australia, and Hosseini, Pärn, et al. (2018) stated that BIM maturity must be accelerated in the country. Furthermore, given the limited success of OSM (Duc, Forsythe and Orr, 2014) and the lack of a planned transition from on-site building to OSM in Australia, its adoption rate of OSM lags behind that of other countries that have innovated and implemented OSM (Khalfan and Maqsood, 2014). These difficulties may limit the effectiveness of the individual implementation of the approaches, and they also prevent BIM application in OSM-based projects as a hybrid approach in Australia from progressing beyond its infancy.

In addition, Yin, et al. (2019) identified a range of research gaps regarding the application of BIM in OSM. Although Vernikos, et al. (2014) highlighted that BIM can improve OSM, its use in OSM has been minimal. Construction professionals and clients have long been cited as being unwilling to use BIM to its maximum potential in OSM owing to the lack of evidence on its possible benefits (Abanda, Tah and Cheung, 2017). According to Yin, et al. (2019, p. 84), “BIM-based generative design for prefabrication” is one of the topics on which more research is needed. This gap in current knowledge can be identified by the lack of a road map that systematically shows areas in which these interactions can be practised.

To fill this knowledge gap, this study evaluates the impact of BIM–OSM interactions on construction project performance. Accordingly, the objectives set against the aim of this study are (a) to evaluate the effects of the BIM and OSM capabilities separately on project performance via key productivity indicators (KPrIs), (b) to identify any BIM–OSM interactions that mediate between the two approaches and (c) to determine the degree of effectiveness of BIM capabilities that guarantee the promised benefits of OSM for project performance. To achieve these objectives, covariance-based structural equation modelling (CB-SEM) was used to analyse data.

Data were collected through a survey. The participants in this study were Australian construction professionals with experience in implementing or background knowledge of BIM and OSM. The results of this study demonstrate the practicality of BIM–OSM interactions that encourage construction professionals and clients to adopt BIM–OSM projects. The study also includes technical information applicable to the planning stages of a project to better implement the hybridisation of BIM–OSM project management processes.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review focused on project performance and the adoption of BIM and OSM techniques individually and concurrently. Section 3 develops the hypotheses, and Section 4 discusses the research methodology. Section 5 describes the data analyses and findings. Section 6 discusses the results and the contributions of this study. Last, Section 7 concludes the paper.

Literature review

The distinction between performance and productivity was delineated by Sabet and Chong (2018), who argued that performance goals may be reached through improved indicators of productivity. Improved control over activities is another means of eliminating likely inefficiencies in dynamic environments, such as complex construction sites (Kenley, 2014). The successful elimination of inefficiencies in a functioning system may be subject to innovation and its effective diffusion. Gambatese and Hallowell (2011) supported Rogers’s (1995) finding that the successful diffusion of innovation needs three critical aspects: idea development, opportunity creation and innovation practice. “Diffusion”, as described by Kale and Arditi (2010, p. 330), is “the process by which an invention is conveyed among and practised by the members of a society over time via certain routes”. Diffusion theory aims to explain the processes, reasons, and trends underlying the spread of new concepts and technologies. The diffusion of technological innovations is a slow process that requires tangible evidence of the actual beneficial application of these new approaches.

Implementation attempts for BIM and OSM have far fallen short of their aims because of a dearth of studies on their systematic adoption. The USA and the UK have adopted legislation and standards to encourage BIM implementation and have thus demonstrated its application (Lea, et al., 2015). Furthermore, the UK government has stipulated that all public sector projects apply a minimum Level 2 BIM (Ullah, Lill and Witt, 2019). In contrast, OSM still faces a lack of more regulatory standards for the work environment and requires greater uniformity across construction components. Many scholars have highlighted the capabilities of these techniques to encourage potential beneficiaries. For instance, Ezcan, Isikdag and Goulding (2013) created an enhanced BIM-based model to address shortcomings in OSM projects, such as insufficient connectivity across technology, processes and people. In addition, Nawari (2012) revealed that BIM connects the stages of design, manufacture, and construction, allowing all stakeholders to access pertinent data. These connections have altered traditional construction processes. Moreover, Abanda, Tah and Cheung (2017) emphasised that projects based on BIM–OSM have significant advantages over traditional building projects.

Project performance

Nassar (2009) developed a combined framework that includes the scope of performance in construction projects. The framework reflects cost, quality, time, safety, and shareholder satisfaction as the main considerations for performance assessment. Incorporating and measuring these dimensions are considered imperative to the operational monitoring of project performance. The ongoing demand for improved construction methods emerges from the need to ensure profitability for stakeholders, clients, and end users. However, the dynamic and agile nature of the construction sector tests the flexibility of these methods. It also raises questions about a technique’s ability to function within a system (Ferrada, Serpell and Skibniewski, 2013). Holton and Burnett (2005) asserted that constantly changing environments may also impede project execution by disrupting stakeholder communication and information flow. Consequently, cost, quality, time, and safety inefficiencies may be inevitable when new techniques are first implemented until their application is calibrated and optimised. The resulting dissatisfaction among project parties may give rise to disagreements during projects, which further obstruct the achievement of improved project performance. According to Walker and Daniels (2019), a cooperative environment is important for improving the performance levels of a project. Moreover, Jha and Iyer (2006) believed that shareholder satisfaction can also contribute to improving project performance. Dozzi and AbouRizk (1993) stated that the terms “performance” and “productivity” are used interchangeably in project performance literature and clarified that the two concepts are complementary.

Background on OSM

Off-site manufacturing has been recognised as a viable solution for meeting the demands of increased construction complexity (Hou, et al., 2020). The invention of OSM, through which standardised construction elements are manufactured, distributed and installed at construction sites, has been welcomed as a breakthrough in construction innovation (Arashpour, et al., 2020). This method could lead to construction efficiencies and increased productivity (Wasim, Serra and Ngo, 2020). For the betterment of the industry and its collective understanding of OSM, it is important to recognise and be cognisant of the further terms of reference used to describe this technique, such as “industrialised building” and “prefabrication” (Khalfan and Maqsood, 2014).

OSM products include volumetric and non-volumetric items, as well as organised concrete and steel structural components, wall panels, electrical and mechanical elements, and full units that are preassembled for various phases of construction (Elnaas, Gidado and Ashton, 2014). A wide range of joinery components are also available for assembly in construction projects (Blismas and Wakefield, 2009).

According to the Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre (2017), a regulated environment can help limit the possibility of negative consequences associated with inefficient material use or scheduling, as well as safety and quality concerns. Eliminating unfavourable influences that contribute to rework increases productivity (Hughes and Thorpe, 2014). OSM reduces not only waste but also the expenditure and time required because fewer resources are committed to waste management. The use of preassembled modules enhances quality, minimises resources, improves safety and risk outcomes, boosts collaboration among project parties, and reduces total project/product costs (Arif and Egbu, 2010).

According to Duc, Forsythe and Orr (2014), the restricted OSM market in Australia is due to a paucity of high-quality prefabricated items. Such challenges jeopardise the timeliness and cost-effectiveness of OSM-based developments. The UK, Malaysia, Hong Kong, China and Australia have all given significant attention to OSM (Li, et al., 2014). Numerous studies have been conducted on OSM over the past decade, but there is still potential for improvement in terms of operational, management, and strategic concerns in order to make OSM more useful to the construction sector (Hossieni, Martek, et al., 2018).

Background on BIM

BIM has been considered a management tool for fostering stakeholder collaboration (Liu, Van Nederveen and Hertogh, 2017). The integration of graphical and non-graphical information in a BIM approach allows project stakeholders to communicate more efficiently throughout the project life cycle (Pezeshki, Soleimani and Darabi, 2019). BIM is a significant innovation that has been widely adopted in architecture, engineering, and construction management (Issa and Olbina, 2015). It enables service time reduction across a variety of disciplines, including for facility managers, cost management consultants, building services designers, and principal contractors (Fox and Hietanen, 2007).

BIM has been identified and recommended by several governments as a viable method to counter poor construction productivity. The UK, as a BIM pioneer, has enforced the use of Level 2 BIM in government projects (Kassem, et al., 2015). Level 2 BIM creates a collaborative environment in which all project participants can share their three-dimensional (3D) models (e.g., models for architecture, structure, and services) (Edirisinghe and London, 2015). BIM capabilities include component specification identification, material quantification and project estimation, 3D visualisation, site accessibility, planning and scheduling, and progress monitoring, all of which contribute directly to the effective use of material, equipment and human resources (Jung and Joo, 2011). BIM adoption has accelerated and diversified the implementation of BIM in businesses in proportion to their expertise and customer demand (Jung and Lee, 2015). According to Aibinu and Papadonikolaki (2020, p. 1), “in order to obtain good results with BIM, adopters must choose the most effective implementation plan that is economically viable”.

The information management capabilities of BIM reinforce other creative approaches and construction processes (Ezcan, Isikdag and Goulding, 2013; Abanda, Tah and Cheung, 2017). When BIM is used in conjunction with another methodology, their capabilities may overlap and accordingly augment the functionality of both. The integration of BIM with other techniques is likely to accelerate its adoption and expand its operational and strategic reach in sustainable development (Manzoor, et al., 2021). For instance, BIM can be used in conjunction with lean building techniques to create a collaborative ecosystem (Sacks, et al., 2010). In addition, Ghalenoei, et al. (2022) emphasised BIM’s information flowing capability in OSM. However, Singh, Sawhney and Borrmann (2019) stated that rule-based scrips should be created to improve practitioners’ BIM integration with other methodologies.

Gelic, Neimann and Wallwork (2016) found that BIM adoption in Australia remains low despite its status as an influential technique. The high cost of hiring BIM-proficient teams and the limits of current software (Alwisy, et al., 2019) and contracting (Migilinskas, et al., 2013) may jeopardise project cost performance and justify BIM’s low adoption. From the perspective of BIM’s influencing qualities, its function and implementation are worthy of additional examination from the standpoint of the diffusion of innovation theory (Hosseini, Banihashemi, et al., 2016).

Interaction between BIM and OSM

Although the performance of OSM-based housing has been discussed to be superior to that of more traditional housing (Pervez, et al., 2022), several obstacles such as “lack of experience, poor communication, budgetary constraints, and stakeholder limits” (Hu, et al., 2019, p. 8) have remained impediments to OSM adoption. According to Mostafa, et al. (2020, p. 1), BIM can help eliminate “design flaws and discrepancies in final product models between designers and manufacturers”, as well as some other hurdles. A BIM element model offers designers many of the components’ necessary product details. These considerable benefits may contribute to the components’ constructability and usage on the building site (Khanzadi, Sheikhkhoshkar and Banihashemi, 2020). Gade, et al. (2019) discovered that BIM may play a mediating function through its collaborative sharing platform, therefore optimising functionality. According to Wynn, et al. (2013), the information technology-based characteristics of BIM can help improve the efficiency of OSM.

According to Ezcan, Isikdag and Goulding (2013, p. 7), the most useful features of BIM in OSM-based projects include “offering an enhanced design, promoting cooperation, and covering accurate and large amounts of information”. Sabet and Chong (2019) emphasised the possibility of integrating the two techniques, which would lead to faster construction; improved quality, cost and safety control; and minimisation of rework on site, or, more broadly, a more sustainable project from conception through to completion. These possibilities are referred to as BIM–OSM interactions, which comprise a road map that identifies the capabilities of OSM and BIM that could be paired to maximise the effectiveness of one another.

Nevertheless, given the lack of empirical research on the use of BIM in OSM, the link between the two techniques is questionable (Tang, Chon and Zhang, 2019). According to Nawari (2012), BIM standards and regulations built entirely for OSM can ensure productivity and efficiency in OSM-based projects. As OSM–BIM interactions have not been investigated in Australia, a road map to show how to practise these interactions is lacking, which has encouraged this research. Therefore, an in-depth literature review is performed in this research for four primary reasons. The first is to clarify project performance, the second is to depict the capabilities of BIM and OSM, the third is to highlight the extent of BIM in OSM, and the fourth is to define existing opportunities through the concurrent adoption of the two techniques.

Hypothesis development

The first stage of this study focused on identifying existing evidence to establish a foundation for this research. Relevant publications were collected by assessing their abstracts. Keywords in the searches included construction, productivity growth/improvement, construction performance, BIM capabilities, OSM capabilities, BIM in construction, OSM in construction, and BIM in OSM. The examination of the theoretical framework required an empirical study. To ensure a solid hypothetical model, the research team conducted a pilot study in which they approached several leading scholars and construction industry representatives, both in person and virtually. These individuals were project managers, supervisors, quantity surveyors, project and site engineers, and architects with professional and academic BIM and OSM backgrounds. The research team discussed the research aim with these participants and collected feedback on the research method. The hypotheses and the research model were narrowed down after a few rounds of pilot studies. The first and second rounds focused on collecting the basis of the hypotheses and construct validity, respectively. To ensure construct validity, the research team conferred with the industry and academic leaders of the first round and verified the measurement constructs. In the pilot studies, the team created statements that highlighted the possible relevance of the interactions and capabilities to ensure content validity. The pilot study participants confirmed that the claims were worded in an easily comprehensible manner, which made them more capable of precisely measuring the objectives. Then, the hypotheses were developed via the discussions about each, as explained in the following.

BIM and project performance

Ghaffarianhoseini, et al. (2017) examined the capabilities of BIM at various stages, including model explanation, on-site coordination, buildability assessment, quantification and estimation, model unification and clash detection, sequential clarification, and data collection and transmission, based on existing literature. Sabet and Chong (2019) argued that in addition to these benefits, BIM can regulate safety considerations, which can significantly boost project productivity. Consequently, extant literature suggests that an in-depth examination is warranted to gain a comprehensive picture of how well BIM capabilities align with the performance scope of projects. A section of this study highlights the implementation of BIM from the standpoint of productivity. To evaluate this assertion in conjunction with Hypothesis 6, the following hypothesis was developed:

H1: BIM has considerable influence on the overall project performance.

OSM and project performance

OSM has created significant opportunities for the construction sector to enhance project performance (Choi, Chen and Kim, 2019). By reviewing relevant literature, Sabet and Chong (2018) identified the major OSM capabilities as automation and serial manufacturing, improved working conditions, earlier return on investment, sustainability outcomes, and safer operations. The capabilities and potential advantages of OSM have raised demand for its application, which is expected to continue to grow internationally. It has been suggested that Australia expedited the deployment of OSM to boost its domestic property market (Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre, 2017). However, concerns about OSM application have hindered such deployment (Wynn, et al., 2013), and further study into ways to increase its applicability is necessary to confirm its advantages. Given that OSM appears capable of improving productivity indicators, research that quantifies the effectiveness of its capabilities in improving project performance may contribute to more complete knowledge of its applicability. To aid in the commercial acceptance of OSM, the following hypothesis was developed:

H2: OSM has considerable influence on the overall project performance.

BIM–OSM interactions and project performance

As aforementioned, Sabet and Chong (2019) evaluated prior literature on the integration of BIM in OSM, and they drew attention to 12 possible OSM–BIM interactions that can enhance KPrIs and lead to optimised performance. They called for further studies to improve the understanding of the viability of these interactions. Site allocation and accessibility, safety, planning and scheduling, procurement and contracts, sustainability, value engineering, information flow, interface management, sequencing, location management and concurrent engineering are all examples of possible interconnections. The following hypotheses were established for examination using the CB-SEM method to investigate the correlation between these two approaches that may positively affect these variables and the overall project performance:

H3: BIM has considerable influence on OSM.

H4: OSM has considerable influence on BIM–OSM interactions.

H5: BIM has considerable influence on BIM–OSM interactions.

H6: BIM–OSM interactions have considerable influence on the overall project performance.

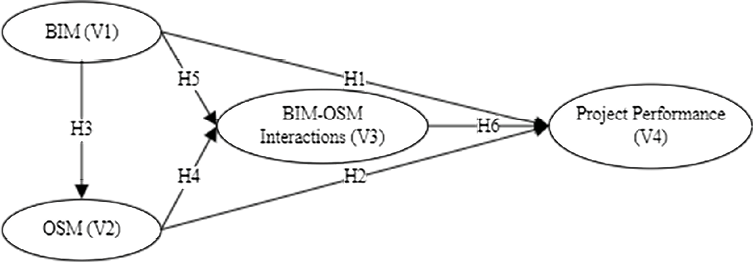

Given the scarcity of studies that measure the interactions between BIM, OSM and KPrIs, the present study built a hypothetical model encompassing four components (see Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1, the standalone capabilities of the two techniques, as well as their interactions, serve as independent factors in the research, while the overall project success (as measured by KPrIs, as already stated) serves as the dependent variable.

Figure 1. Hypothetical research model.

Research methodology

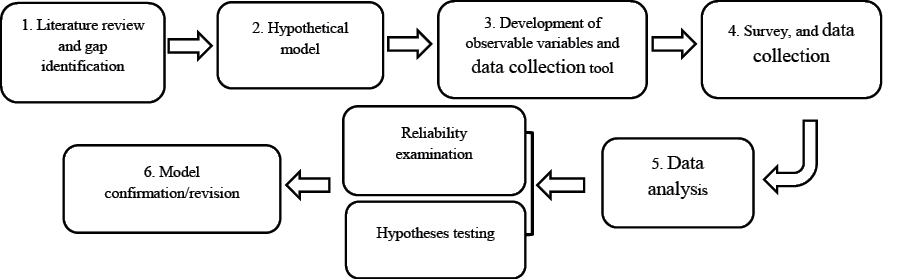

The steps of this investigation are depicted in Figure 2. This study had two main stages. The first was a comprehensive literature review to identify the research gap, which was found to be the lack of a road map on how to systematically apply BIM in OSM. This gap motivated the research team to develop a theoretical framework and then conduct an empirical study in the second stage to evaluate the relationships between the variables in the research model. A scoping review approach was implemented in the literature review. Pham, et al. (2014) stated that this type of review approach provides the basis of any potential synergies between research variables. Peters, et al. (2015) asserted that such an approach is supportive to new systems on which there is insufficient literature.

Figure 2. Flowchart of research stages.

The comprehensive literature review and the pilot studies revealed that quantitative research using a questionnaire would be most suitable for this research. Therefore, the need to conduct quantitative research was the basis for the selection and development of a questionnaire as the data collection instrument. The pilot study participants advised the research team to design a straightforward, effective questionnaire that could motivate respondents to complete and return it. Most of those participants suggested that a 5-point Likert scale be used.

In quantitative research, the identification of capable respondents is important in the design of a reliable research tool. In addition, the sampling strategy has a clear, direct relationship with the reliability and accuracy of outcomes in quantitative research (Holton and Burnett, 2005). The steps in the sampling strategy applied in this study included selecting the target population, ensuring the accessibility of the population, finalising the eligibility criteria, outlining the sampling plan and recruiting the sample. Morse (1991, p. 127) stated that “purposeful sampling” needs to be followed in the data collection stage, which involves selecting informants who are best able to meet the informational needs of the study.

As aforementioned, six hypotheses were developed to build a hypothetical model for quantifying the correlations between OSM, BIM, BIM–OSM interactions and the overall project performance. This model contains four variables. The individual capabilities of the two approaches, as well as their interactions, were independent variables, whereas the overall project success was the dependent variable. The capabilities of the two techniques were “observable criteria” for assessing the practicality of OSM and BIM. In addition, observable factors for evaluating the viability of BIM–OSM interactions included a variety of descriptions. Table 1 shows the various pathways and hypothesised effects between variables.

Table 2 lists the constructions and the observable variables that may be used to quantify the latent variables. The elements that influence the choice of an appropriate research technique include constraints such as financial and time constraints, research potential and the willingness of (human) participants (Brannen, 2005). A hypothetical model was developed using the hypotheses (H1–H6) and was assessed using the CB-SEM technique via the Amos software to analyse the relationships between variables in the research model. Data reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. In addition, regression tests were applied to detect potential associations and degrees of influence between the variables in this model. Last, the findings of the hypothesis testing revealed whether the model was valid or required revision.

Data analysis and findings

Data collection

First, a link to the questionnaire was sent via Qualtrics to construction professionals with relevant skills and experience, and an additional paper questionnaire was also circulated. Engineers Australia made a substantial contribution to this study. The survey was formally announced to its participants, who were encouraged to participate. Next, the research team contacted those practitioners via LinkedIn and informed them of the study. The team found LinkedIn to be the most useful site for learning about potential participants’ backgrounds. Based on their experience, the research team targeted practitioners who were skilled in implementing or had knowledge of OSM and BIM. The scope for this study was Australia, and the research team intended to generalise the outcome to the entire country. The data collection period was longer than initially anticipated because a limited number of responses were obtained. The main reason was that practitioners lacked sufficient experience in using either BIM or OSM. In all, 687 questionnaires were circulated.

Studies on the adoption of innovative techniques and the implementation of innovations in the construction sector frequently have a low response rate (Ahankoob, et al., 2018). For instance, the response rate for Ling’s (2003) survey on construction innovations was just 6%. Contacting a representative (i.e., one who represents a group of practitioners) of firms and organisations is an effective way of encouraging professionals to engage. Representatives were requested to answer the questionnaire based on the background of their knowledge, project experience and learnings through careful reviewing of project reports. The respondents rated the observable variables on a 5-point Likert scale. Their responses were analysed using SEM. A bootstrapping technique was also used to improve the accuracy of data analysis.

The response rate was low, and only 77 valid returned questionnaires out of the 687 circulated questionnaires were included in the data analysis.

Reliability and validity of constructs

Cronbach’s alpha (with a coefficient greater than 0.7) was used to assess the reliability of scales (Santos, 1999). The questionnaire’s reliability was confirmed using Cronbach’s alpha, which yielded a coefficient of 0.94. Thus, the dependability of the data was established. Given these arguments, the validity and reliability of the results produced from valid content and constructs followed by reliable surveys are acceptable.

Table 3 presents the factor loadings for each observed variable, which represent an appropriate correlation coefficient (>0.3). In other words, each variable contributed suitably to the questionnaire’s competence for measuring the construct intended to be measured.

Hypothesis assessment and interpretation

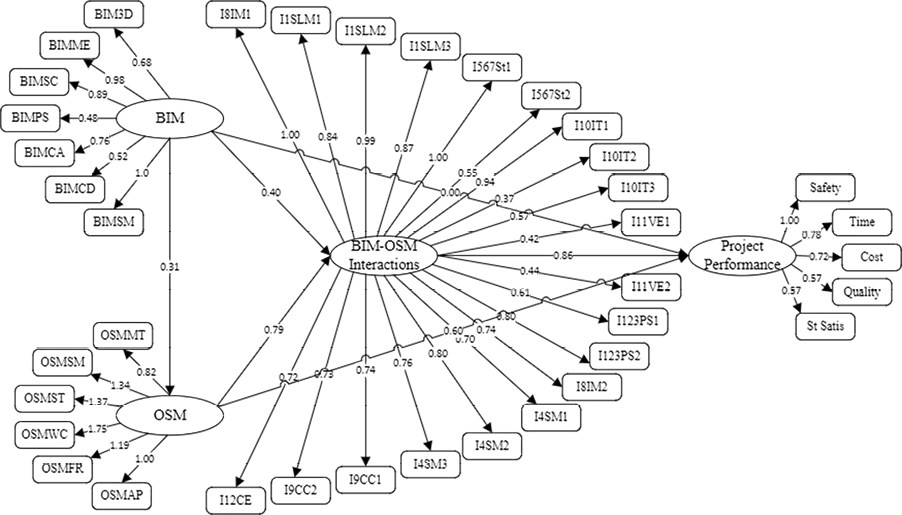

The hypotheses were tested using CB-SEM with bootstrapping. Using the Amos software, the standardised path coefficient (β) was determined via SEM. The p-values of the first two pathways were greater than 0.05, as shown in Table 4. This means that OSM and BIM did not have a major impact on the overall project performance. Therefore, H1 and H2 were not supported. The findings of this study on individual OSM and BIM applications in Australia are consistent with prior findings on the limited success of OSM (Duc, Forsythe and Orr, 2014) and immature BIM adoption (Gelic, Neimann and Wallwork, 2016). As can be observed from the results in the third row of Table 4, BIM had a substantial impact on OSM (β = 0.4, p = 0.05). These results supported H3. Furthermore, both OSM (β = 0.79, p = 0.05) and BIM (β = 0.40, p = 0.05) had a substantial impact on the OSM–BIM interactions. This means that each method can interact with the other. These results supported H4 and H5. Last, the interaction between BIM and OSM influenced the overall project performance considerably (β = 0.86, p = 0.05). In other words, the capabilities of each approach resulted in positive OSM–BIM interactions, which improved the KPrIs and contributed to the predicted performance of projects. Thus, H6 was supported.

The path coefficients (regression weights) of each approach’s capabilities, as well as the relationships between OSM and BIM, are shown in Figure 3. For example, the regression weight of 3D BIM was 0.68, that of OSM automation and series production was 1, and that of concurrent engineering (I12CE) was 0.72. The weight of the interface management, comprised I8IM1 (1.00) and I8IM2 (0.87). In terms of their direct influence on the overall project performance, the weights of OSM and BIM were 0.49 and 0.00, respectively. The BIM weight of 0.00 shows that the respondents were uncertain whether the individual application of BIM has a direct, positive impact at this point of practice in Australia. This ambiguous position of BIM may stem from its low adoption in Australia (Gelic, Neimann and Wallwork, 2016), which has resulted in its immaturity in the Australian market (Hosseini, Pärn, et al., 2018). Most interactions were given a weight of 0.70 or higher, but OSM and BIM were each given a weight of 0.40 for their direct influence on interaction formation. For their direct impact on the overall project performance, the BIM–OSM interactions received a weight of 0.89. The indirect effects of OSM and BIM on the overall project performance were 0.68 (0.79 * 0.86) and 0.35 (0.40 * 0.86), respectively.

Figure 3. Path coefficients (SEM model). SEM, structural equation modelling

Discussion and contributions

The feasibility of the individual capabilities of BIM and OSM approaches—and the feasibility of their combined capabilities, referred to as BIM–OSM interactions—were assessed in this study. Complicated correlations between the interrelated variables were tested to quantify the feasibility of combining the capabilities of these two approaches. This measurement allowed respondents in this study to assess the capabilities of the strategies in relation to their prospective interactions. The evaluation of the hypothetical model resulted in the rejection of two hypotheses out of the six tested. In other words, this study clarified that the individual application of OSM or BIM does not affect the overall project performance, but their concurrent application can significantly affect the project performance dimensions.

First, this study contributes to the literature by indicating that a range of theoretical collaborative opportunities, referred to as interactions between OSM and BIM, are mediators that improve KPrIs and thus the overall project performance. In addition to revealing the effects of these interactions, this study suggested how and when these should be used throughout a project. Thus, this study shows that the interactions found have practical consequences for planning and management. For instance, an expanded BIM model accurately specifies the needed technical parameters for building components. These requirements significantly reduce the possibility of construction errors. Meanwhile, OSM allows automation and series manufacturing, both of which contribute greatly to a more rapid flow of advancement and more rapid progress of construction projects. As a result, a BIM–OSM system may give precise technical requirements for a building project. This is critical to the project’s success in serial production since correcting manufacturing faults consumes time and money, which can undermine initiatives. These skills can aid in the management of interfaces and satisfy stakeholders in a BIM–OSM-based project.

To base this interactive approach, three critical aspects of innovation—idea development, opportunity creation, and diffusion—were defined. This hybrid system could be counted as a unique method for ensuring the entire project performance that may be extensively implemented in the industry. This study discussed that the implementation of innovation and the development of coordination between novel techniques in real-life situations are fundamental to accelerating the evolution of, and addressing future demand in, the construction industry. It emphasised that the success rate of innovation requires a systematic implementation of new techniques. Thus, second, this study satisfies the objective of the diffusion of innovation theory, as the research outcomes are consistent with the principle of this theory.

Conclusion

The links between BIM, OSM, BIM–OSM interactions, and the overall project performance were investigated in this study. CB-SEM was used to analyse the data and test the hypotheses, with bootstrapping added to improve the accuracy of the data analysis. The findings reveal that BIM and OSM capabilities have not been systematically implemented in Australia and that the capabilities of OSM and BIM as singular methods had no significant impact on the overall project performance when applied individually in a project. However, BIM was found to substantially influence OSM, which implies the presence of symbiotic capabilities, and to accordingly optimise each other’s effectiveness.

This study demonstrates the degree of influence of each method (regression weight) and the approach (direct and indirect effects) on the overall project performance (see Figure 3). The development of their interactions suggests a positive association in the systematic implementation of these approaches. By improving KPrIs, these interactions are capable of optimising the performance scopes of projects, such as time, cost, quality, safety, and stakeholder satisfaction, suggesting that productivity increase is followed by improved project performance in a BIM–OSM-based project. The implementation of OSM and BIM in a hybrid system could allow the identified interactions to fulfil the objectives of both techniques. The prominent output of this study is a road map, as the empirical contribution, which shows how effective BIM–OSM interactions can be applied in the planning and management of OSM-based projects. Therefore, this hybrid system represents an innovative process for overall project performance, which can be widely applied in the industry and added to the body of knowledge on the concurrent implementation of OSM and BIM.

The study findings may encourage clients and stakeholders to adopt hybrid BIM–OSM projects to improve the overall project performance. Nevertheless, the findings cannot be applied to other countries, as the research scope was limited to Australia. Moreover, the outputs of this study align with the diffusion of innovation theory, as this study illustrated idea development, opportunity creation, and practice of innovation.

Limitations of the study

This study has some limitations. The first is the lack of projects that fully applied BIM or OSM techniques or of case studies that reported the combined application of the two techniques. A report detailing a BIM–OSM-based project could serve as a theoretical benchmark and help evaluate the concept. The second limitation is the lack of professionals with experience in using both techniques. The third is that the contractors and clients approached for this study showed no interest in adopting new methods. Thus, practitioners should be educated on the benefits of a hybrid BIM–OSM system to foster more collaborative research.

Data availability statement

The corresponding author can make available data, models or codes that support the findings of this study upon reasonable request.

References

Abanda, F., Tah, J. and Cheung, F., 2017. BIM in off-site manufacturing for buildings. Journal of Building Engineering, [e-journal] 14, pp.89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2017.10.002

Ahankoob, A., Manley, K., Hon, C. and Drongemuller, R., 2018. The impact of building information modelling (BIM) maturity and experience on contractor absorptive capacity. Architectural Engineering and Design Management, [e-journal] 14(5), pp.363–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2018.1467828

Aibinu, A.A. and Papadonikolaki, E., 2020. Conceptualizing and operationalizing team task interdependences: BIM implementation assessment using effort distribution analytics. Construction Management and Economics, [e-journal] 38(5), pp.420–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2019.1623409

Alwisy, A., Hamdan, S.B., Barkokebas, B., Bouferguene, A. and Al-Hussein, M.A., 2019. BIM-based automation of design and drafting for manufacturing of wood panels for modular residential buildings. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 19(3), pp.187–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2017.1411458

Arashpour, M., Heidarpour, A., Nezhad, A.A., Hosseinifard, Z., Chileshe, N. and Hosseini, R., 2020. Performance-based control of variability and tolerance in off-site manufacture and assembly: optimization of penalty on poor production quality. Construction Management and Economics, [e-journal] 38(6), pp.502–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2019.1616789

Arif, M. and Egbu, C., 2010. Making a case for offsite construction in China. Engineering. Construction and Architectural Management, [e-journal] 17(6), pp. 536–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699981011090170

Azhar, S., 2011. Building information modeling (BIM): Trends, benefits, risks, and challenges for the AEC industry. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 11(3), pp. 241–52. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LM.1943-5630.0000127

Babič, N.Č., Podbreznik, P. and Rebolj, D., 2010. Integrating resource production and construction using BIM. Automation in Construction, 19(50), pp.539–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2009.11.005

Blismas, N. and Wakefield, R., 2009. Drivers, constraints and the future of offsite manufacture in Australia. Construction Innovation, 9(1), pp. 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/14714170910931552

Bortolini, R., Formoso, C.T. and Viana, D.D., 2019. Site logistics planning and control for engineer-to-order prefabricated building systems using BIM 4D modeling. Automation in Construction, 98, pp.248–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2018.11.031

Boyd, N., Khalfan, M. M. and Maqsood, T., 2013. Off-site construction of apartment buildings. Journal of Architectural Engineering, 19(1), pp.51–57. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)AE.1943-5568.0000091

Brannen, J., 2005. Mixing methods: the entry of qualitative and quantitative approaches into the research process. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(3), pp.173–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570500154642

Chao-Duivis, M., 2011. Some legal aspects of BIM in establishing a collaborative relationship. In: The management and innovation for a sustainable built environment, MISBE 2011, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 20–23 June 2011, Delft University of Technology.

Choi, J.O., Chen, X.B. and Kim, T.W., 2019. Opportunities and challenges of modular methods in dense urban environment. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 19(2), pp.93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2017.1382093

Dolage, D. and Chan, P., 2013. Productivity in construction-a critical review of research. Journal of the Institution of Engineers, 46(4), pp.31–42. https://doi.org/10.4038/engineer.v46i4.6808

Dozzi, S.P. and AbouRizk, S.M.,1993. Productivity in construction. Ottawa: Institute for Research in Construction, National Research Council Ottawa.

Duc, E., Forsythe, P. and Orr, K., 2014. Is there really a case for off-site manufacturing? In: The 31st international symposium on automation and robotics in construction and mining, ISARC 2014-proceedings. Sydney: Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building, University of Technology. pp.238–246. https://doi.org/10.22260/ISARC2014/0032

Eastman, C.M., and Sacks, R., 2008. Relative productivity in the AEC industries in the United States for on-site and off-site activities. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 134(7), pp.517–526. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2008)134:7(517)

Edirisinghe, R. and London K., 2015. Comparative analysis of international and national level BIM standardization efforts and BIM adoption. In: Proceedings of the 32nd CIB W78 conference. Eindhoven, The Netherlands: Eindhoven University of Technology. pp.149–158, CIB.

Elnaas, H., Ashton P. and Gidado, K., 2009. Decision making process for using off-site manufacturing systems for housing projects. In: The 25th annual ARCOM conference, Nottingham, UK, 7–9 September 2009. Reading, UK: Association of Researchers in Construction Management.

Elnaas, H., Gidado, K., and Ashton, P., 2014. Factors and drivers effecting the decision of using off-site manufacturing (OSM) systems in house building industry. Journal of Engineering, Project, and Production Management, 4(1), pp.51–58. https://doi.org/10.32738/JEPPM.201401.0006

Ezcan, V., Isikdag, U. and Goulding, J., 2013. BIM and off-site manufacturing: recent research and opportunities. In: Proceedings of the 19th CIB world building congress, Brisbane, Australia: Queensland University of Technology. Available at: https://wbc2013.apps.qut.edu.au/papers/cibwbc2013_submission_118.pdf.

Fadoul, A., Tizani, W. and Koch, C., 2017. Constructability assessment model for buildings design. In: C. Koch, W. Tizani and J. Ninic, eds. Proceedings of the 24th EG-ICE international workshop on intelligent computing in engineering 2017, Nottingham, UK: European Group for Intelligent Computing in Engineering. pp.86–95.

Fan, S.L., Chong, H.Y., Liao, P.C. and Lee, C.Y., 2019. Latent provisions for Building Information Modeling (BIM) contracts: a social network analysis approach. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 23(4), pp.1427–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-0064-8

Farnsworth, C.B., Beveridge, S., Miller, K.R., and Christofferson, J.P., 2015. Application, advantages, and methods associated with using BIM in commercial construction. International Journal of Construction Education and Research, 11(3), pp.218–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/15578771.2013.865683

Ferrada, X., Serpell, A. and Skibniewski, M., 2013. Selection of construction methods: a knowledge-based approach. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, p.938503. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/938503

Fox, S. and Hietanen, J., 2007. Interorganizational use of building information models: potential for automational, informational and transformational effects. Construction Management and Economics, [e-journal] 25(3), pp.289–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190600892995

Gade, P.N., Gade A.N., Otrel-Cass, K. and Svidt, K., 2019. A holistic analysis of a BIM-mediated building design process using activity theory. Construction Management and Economics, [e-journal] 37(6), pp.336–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2018.1533644

Gambatese, J.A., and Hallowell, M., 2011. Enabling and measuring innovation in the construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 29(6), pp.553–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2011.570357

Gelic, G., Neimann, R. and Wallwork, A., 2016. What you need to know about BIM in Australia. IPWEA Blogs, [blog], 2 August. Available at: https://www.ipwea.org/blogs/intouch/2016/08/01/what-you-need-to-know-about -bim-in-australia [Accessed 9 January 2018].

Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Tookey, J., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Naismith, N., Azhar, S., Efimova, O. and Raahemifar, K., 2017. Building Information Modelling (BIM) uptake: clear benefits, understanding its implementation, risks and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 75, pp.1046–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.083

Ghalenoei, K.N., Jelodar, B.M., Paes, D. and Sutrisna, M., 2022.Challenges of offsite construction and BIM implementation: providing a framework for integration in New Zealand. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, [e-journal], 13(4), pp.780–808. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-07-2022-0139

Holton, E.F. and Burnett, M.F., 2005. The basics of quantitative research. In: R.A. Swanson and E.F. Holton, eds. Research in organizations: foundations and methods of inquiry. San Fransico: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. pp.29–44.

Hosseini, M.R., Banihashemi, S., Chileshe, N., Namzadi, M. O., Udaeja, C., Rameezdeen, R., & McCuen, T., 2016. BIM adoption within Australian Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs): an innovation diffusion model. Construction Economics and Building, [e-journal] 16(3), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v16i3.5159

Hosseini, M.R., Banihashemi, S., Martek, I., Golizadeh, H. and Ghodoosi, F., 2018. Sustainable delivery of megaprojects in Iran: integrated model of contextual factors. Journal of Management in Engineering, [e-journal] 34(2), pp.1–12. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000587

Hosseini, M.R., Maghrebi, M., Akbarnezhad, A., Martek, I. and Arashpour, M., 2018. Analysis of citation networks in building information modeling research. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, [e-journal] 144(8). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001492

Hosseini, M.R., Maghrebi, M., Chileshe, N. and Waller, S.T., 2016. An investigation into the perceived quality of communications in dispersed construction project teams. In: J.L. Perdomo-Rivera, A. Gonzáles-Quevedo, C.L. del Puerto, F. Maldonado-Fortunet, O.I. Molina-Bas, eds. Construction Research Congress 2016. Reston, VA: ASCE. pp.1813–22. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784479827.181

Hosseini, M.R., Martek, I., Zavadskas, E.K., Aibinu, A.A., Arashpour, M. and Chileshe, N., 2018. Critical evaluation of off-site construction research: a scientometric analysis. Automation in Construction, 87, pp.235–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.12.002

Hosseini, M.R., Pärn, E., Edwards, D., Papadonikolaki, E., and Oraee, M., 2018. Roadmap to mature BIM use in Australian SMEs: competitive dynamics perspective. Journal of Management in Engineering, [e-journal] 34(5). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000636

Hou, L., Tan, Y., Luo, W., Xu, S., Mao, C. and Moon, S., 2020. Towards a more extensive application of off-site construction: a technological review. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 22(11), pp.2154–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1768463

Hu, X., Chong, H.Y., Wang, X. and London, K., 2019. Understanding stakeholders in off-site manufacturing: a literature review. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, [e-journal] 145(8). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001674

Hughes, R. and Thorpe, D., 2014. A review of enabling factors in construction industry productivity in an Australian environment. Construction Innovation, [e-journal] 14(2), pp.210–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-03-2013-0016

Issa, R.R. and Olbina, S. eds., 2015. Building information modeling: applications and practices. Reston, VA: ASCE. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784413982

Jha, K.N. and Iyer, K.C., 2006. Critical determinants of project coordination. International Journal of Project Management, 24(4), pp.314–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2005.11.005

Jrade, A. and Lessard, J., 2015. An integrated BIM system to track the time and cost of construction projects: a case study. Journal of Construction Engineering, [e-journal]. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/579486

Jung, W. and Lee, G., 2015. The status of BIM adoption on six continents. International Journal of Civil, Environmental, Structural, Construction and Architectural Engineering, 9(5), pp.444–48.

Jung, Y. and Joo, M., 2011. Building information modelling (BIM) framework for practical implementation. Automation in Construction, 20(2), pp.126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2010.09.010

Juszczyk, M., Výskala, M., and Zima, K., 2015. Prospects for the use of BIM in Poland and the Czech Republic: preliminary research results. Procedia Engineering, 123, 250–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.10.086

Kale, S. and Arditi, D., 2010. Innovation diffusion modeling in the construction industry. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 136(3), pp.329–40. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000134

Kassem, M., Kelly, G., Dawood, N., Serginson, M. and Lockley, S., 2015. BIM in facilities management applications: a case study of a large university complex. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, [e-journal] 5(3), pp.261–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-02-2014-0011

Kenley, R., 2014. Productivity improvement in the construction process. Construction Management and Economics, 32(6), pp.489–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2014.930500

Khalfan, M. and Maqsood, T., 2014. Current state of off-site manufacturing in Australian and Chinese residential construction. Journal of Construction Engineering, [e-journal]. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/164863

Khanzadi, M., Sheikhkhoshkar, M., Banihashemi, S., 2020. BIM applications toward key performance indicators of construction projects in Iran. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 20(4), pp.305–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2018.1484852

Kiani, I., Sadeghifam, A.N., Ghomi, S.K. and Marsono, A.K.B., 2015. Barriers to implementation of building information modeling in scheduling and planning phase in Iran. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 9(5), pp.91–7.

Lea, G., Ganah, A., Goulding, J. and Ainsworth, N., 2015.Identification and analysis of UK and US BIM standards to aid collaboration. WIT Transactions on the Built Environment, [e-journal] 149, pp.505–16. https://doi.org/10.2495/BIM150411

Lee, J. and Kim, J., 2017. BIM-based 4D simulation to improve module manufacturing productivity for sustainable building projects. Sustainability, [e-journal] 9(3), p.426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030426

Lee, W., Kang, S., Moh, R., Wu, R., Hsieh, H. and Shu, Z., 2015. Application of BIM coordination technology to HSR Changhua station. Visualization in Engineering, [e-journal] 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40327-014-0008-9

Li, Z., Shen, G.Q., and Xue, X., 2014. Critical review of the research on the management of prefabricated construction. Habitat International, [e-journal] 43, 240–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.04.001

Ling, F.Y.Y., 2003. Managing the implementation of construction innovations. Construction Management and Economics, [e-journal] 21(6), pp.635–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144619032000123725

Liu, Y., Van Nederveen, S. and Hertogh, M., 2017. Understanding effects of BIM on collaborative design and construction: an empirical study in China. International Journal of Project Management, 35(4), pp.686–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.06.007

Liu, Z., Osmani, M., Demian, P. and Baldwin, A.N., 2011. The potential use of BIM to aid construction waste minimalisation. In: The CIB W78-W102 2011: international conference. Sophia Antipolis, France, 26-28 October 2011, paper 53, Loughborough University.

Luth, G.P., Schorer, A. and Turkan, Y., 2014. Lessons from using BIM to increase design-construction integration. Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction, 19(1), pp.103–10. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)SC.1943-5576.0000200

Manzoor, B., Othman, I., Gardezi, S.S.S. and Harirchian, E., 2021. Strategies for Adopting building information modeling (BIM) in sustainable building projects: a case of Malaysia. Buildings, [e-journal] 11, p.249. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11060249

Martinez, P., Ahmad, R. and Al-Hussein, M., 2019. Automatic Selection tool of quality control specifications for off-site construction manufacturing products: a BIM-based ontology model approach. In: M. Al-Hussein, ed. Modular and offsite construction (MOC) summit proceedings. Alberta: University of Alberta. pp. 141–148. https://doi.org/10.29173/mocs87

Martinez-Aires, M.D., Lopez-Alonso, M. and Martinez-Rojas M., 2018. Building information modeling and safety management: a systematic review. Safety Science, [e-journal] 101, pp.11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.08.015

Migilinskas, D., Popov, V., Juocevicius, V. and Ustinovichius, L., 2013. The benefits, obstacles and problems of practical BIM implementation. Procedia Engineering, [e-journal] 57(1), pp.767–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2013.04.097

Morse, J.M.,1991. Strategies for sampling. In: J.M. Morse, ed. Qualitative nursing research: a contemporary dialogue. London: Sage. pp.127–45. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349015.n16

Mostafa, S., Kim, K.P., Tam, V.W. and Rahnamayie zekavat, P., 2020. Exploring the status, benefits, barriers and opportunities of using BIM for advancing prefabrication practice. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 20(2), pp.146–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2018.1484555

Nassar, N.K., 2009. An integrated framework for evaluation of performance of construction projects. In: PMI® global congress, North America, Orlando, Florida, 10–13 October 2009. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Nath, T., Attarzadeh, M., Tiong, R.L., Chidambaram, C. and Yu, Z., 2015. Productivity improvement of precast shop drawings generation through BIM-based process re-engineering. Automation in Construction, 54(6), pp.54–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2015.03.014

Nawari, N.O., 2012. BIM standard in off-site construction. Journal of Architectural Engineering, [e-journal] 18(2), pp.107–13. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)AE.1943-5568.0000056

Ocheoha, I.A. and Moselhi, O., 2018. A BIM-based supply chain integration for prefabrication and modularization. In: M. Al-Hussein, ed. Modular and offsite construction (MOC) summit proceedings. Alberta: University of Alberta. https://doi.org/10.29173/mocs35

Oti-Sarpong, K., Shojaei, R.S., Dakhli, Z., Burgess, G. and Zaki, M., 2022. How countries achieve greater use of offsite manufacturing to build new housing: identifying typologies through institutional theory. Sustainable Cities and Societies, [e-journal] 76. p.103493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103403

Pan, W., Gibb, A.G. and Dainty, A.R., 2012. Strategies for integrating the use of off-site production technologies in house building. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, [e-journal] 138(11), pp.1331–40. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000544

Pervez, H., Ali, Y., Pamucar, D., Garai-Fodor, M. and Csiszárik-Kocsir, Á., 2022. Evaluation of critical risk factors in the implementation of modular construction. PLoS One, [e-journal] 17(8), p.e0272448. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272448

Peters, M.D., Godfrey, C.M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C.B., 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Pezeshki, Z., Soleimani, A. and Darabi, A., 2019. Application of BEM and using BIM database for BEM: a review. Journal of Building Engineering, [e-journal] 23, pp.1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.01.021

Pham, M.T., Rajić, A., Greig, J.D., Sargeant, J.M., Papadopoulos, A. and McEwen, S.A., 2014. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, [e-journal] 5(4), pp.371–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

Rathnayake, A. and Middleton, C., 2023. Systematic review of the literature on construction productivity. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, [e-journal] 149(6). https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-13045

Rogers, E.M., 1995. Diffusion of innovation, 4th ed. New York: Free Press.

Sabet, P. and Chong, H.Y., 2018. A conceptual hybrid OSM-BIM framework to improve construction project performance. In: K. Do, M. Sutrisna, B. Cooper-Cooke and O. Olatuji, eds. Proceedings of the educating building professionals for the future in the globalised world. Perth: Curtin University. pp. 204–13.

Sabet, P. and Chong, H.Y., 2019. Interactions between building information modelling and off-site manufacturing for productivity improvement. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, [e-journal] 13(2), pp.233–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-08-2018-0168

Sacks, R., Koskela, L., Dave, B.A. and Owen, R., 2010. Interaction of lean and building information modeling in construction. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 136(9), pp.968–80 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000203

Santos, J.R.A., 1999. Cronbach’s alpha: A tool for assessing the reliability of scales. Journal of Extension, 37(2), pp.1–5.

Santos, R., Costa, A.A., Silvestre, J.D. and Pyl, L., 2019. Informetric analysis and review of literature on the role of BIM in sustainable construction. Automation in Construction, [e-journal] 103, pp.221–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.02.022

Shahpari, M., Mehdizadeh, F., Pishvaee, M.S. and Piri, S., 2020. Assessing the productivity of prefabricated and in-situ construction systems using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making method. Journal of Building Engineering, 27(6), p.100979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100979

Shang, Z. and Shen, Z., 2016. A framework for a site safety assessment model using statistical 4D BIM-based spatial-temporal collision detection. In: J.L. Perdomo-Rivera, A. Gonzáles-Quevedo, C.L. del Puerto, F. Maldonado-Fortunet, O.I. Molina-Bas, eds. Construction Research Congress 2016. Reston, VA: ASCE. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784479827.218

Singh, M.M., Sawhney, A. and Borrmann, A., 2019. Integrating rules of modular coordination to improve model authoring in BIM. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 19(1), pp.15–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2017.1358077

Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre, 2017. Accelerating the mainstreaming of building manufacture in Australia. Final industry report Project 1.42. Perth: Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre.

Tang, X., Chon, H.Y. and Zhang, W., 2019. Relationship between BIM implementation and performance of OSM projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, [e-journal] 35(5). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000704

Tibaut, A., Rebolj, D. and Perc, M.N., 2016. Interoperability requirements for automated manufacturing systems in construction. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, [e-journal] 27(1), pp.251–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-013-0862-7

Ullah, K., Lill, I. and Witt, E., 2019. An overview of BIM adoption in the construction industry: benefits and barriers. In: I. Lill and E. Witt, ed. 10th Nordic conference on construction economics and organization (Emerald Reach Proceedings Series, vol. 2), Leeds: Emerald. pp.297–303. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2516-285320190000002052

Utiome, E. and Drogemuller, R., 2013. An approach for extending Building Information Models (BIM) to specifications. In: Z. Ma, Z. Hu, H. Guo and J. Zhang, eds. Proceedings of the 30th CIB W78 international conference on applications of IT in the AEC industry. Tsinghua, China: Tsinghua University. pp.290–99.

Vernikos, V.K., Goodier, C.I., Broyd, T.W., Robery, P.C. and Gibb, A.G., 2014. Building information modelling and its effect on off-site construction in UK civil engineering. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineering-Management, Procurement and Law, 167(3), pp.152–59. https://doi.org/10.1680/mpal.13.00031

Walker, G.B. and Daniels, S.E., 2019. Collaboration in environmental conflict management and decision-making: comparing best practices with insights from collaborative learning work. Frontiers in Communication, [e-journal] 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00002

Wang, J., Wang, X., Shou, W., Chong, H.Y. and Guo, J., 2016. Building information modeling-based integration of MEP layout designs and constructability. Automation in Construction, [e-journal] 61, pp.134–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2015.10.003

Wasim, M., Serra, P.V. and Ngo, T.D., 2020. Design for manufacturing and assembly for sustainable, quick and cost-effective prefabricated construction–a review. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] 22(15), pp.3014–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1837720

Woo, J.H., 2006. Building information modeling and pedagogical challenges. In: T. Sulbaran and G. Cummings, eds. 2007. Proceedings of the 43rd ASC national annual conference: Loveland, CO: Associated Schools of Construction. pp.12–14.

Wu, S., Wood, G., Ginige, K. and Jong, S. W., 2014. A technical review of BIM based cost estimating in UK quantity surveying practice, standards and tools. Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon), 19: 534–62. Available at: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/22902.

Wynn, M.T., Ouyang, C., Low, W.Z., Kanjanabootra, S., Harfield, T. and Kenley, R., 2013. A process-oriented approach to supporting off-site manufacture in construction projects. In: K. Manley, K. Hampson, and S. Kajewski, eds. Proceedings organisation and management of construction: selected papers presented at the CIB world building congress – construction and society [CIB Publication 384]. Delft, The Netherlands: International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction, pp. 13-25.

Yeoh, J.K.W., Wong, J.H. and Peng, L., 2016. Integrating crane information models in BIM for checking the compliance of lifting plan requirements. In: ISARC. Proceedings of the international symposium on automation and robotics in construction, vol. 33, p.1. IAARC Publications. https://doi.org/10.22260/ISARC2016/0116

Yin, X., Liu, H., Chen, Y. and Al-Hussein, M., 2019. Building information modelling for off-site construction: review and future directions. Automation in Construction, [e-journal] 101, pp.72–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.01.010

Zhai, X., Reed, R. and Mills, A., 2014. Embracing off-site innovation in construction in China to enhance a sustainable built environment in urban housing. International Journal of Construction Management, 14(3), pp.123–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2014.922727

Zhang, S., Sulankivi, K., Kiviniemi, M., Romo, I., Eastman, C.M. and Teizer, J., 2015. BIM-based fall hazard identification and prevention in construction safety planning. Safety Science, [e-journal] 72, pp.31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.08.001

Ziwen, L., Bon-Gang, H. and Minghan, L., 2023. Prefabricated and prefinished volumetric construction: assessing implementation status, perceived benefits, and critical risk factors in the Singapore built environment sector. Journal of Management in Engineering, [e-journal] 39(6). https://doi.org/10.1061/JMENEA.MEENG-5455