Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 24, No. 4/5

December 2024

RESEARCH ARTICLE

State of Market Intelligence Development within Construction Companies: Evidence from Ghana

Joseph Asante1, *, Ernest Kissi2 , Alex Acheampong3 , Edward Badu4

1 Sunyani Technical University, Sunyani, Ghana, joseph.asante@stu.edu.gh

2 Kwame Nkrumah University of Science Technology/University of Johannesburg, Kumasi/Johannesburg, Ghana/South africa, ernestkissi@knust.edu.gh

3 Kwame Nkrumah University of Science Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, aacheampong.cap@knust.edu.gh

4 Kwame Nkrumah University of Science Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, ebadu.cap@knust.edu.gh

Corresponding author: Joseph Asante, Sunyani Technical University, Sunyani, Ghana,

joseph.asante@stu.edu.gh

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v24i4/5.8909

Article History: Received 14/12/2023; Revised 13/06/2024; Accepted 06/09/2024; Published 23/12/2024

Citation: Asante, J., Kissi, E., Acheampong, A., Badu, E. 2024. State of Market Intelligence Development within Construction Companies: Evidence from Ghana. Construction Economics and Building, 24:4/5, 98–113. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v24i4/5.8909

Abstract

Market intelligence (MI) forms the bedrock of the marketing concept, serving as a vital component in market-oriented strategic planning and execution. However, construction companies (CCs) have been criticized for not realizing the value of MI. Therefore, the objective of this study is to assess the current state of MI development within CCs in Ghana. Using a purposive sampling approach, the data was collected using a forced-choice answer interview guide with a sample of 56 CCs. The results of the interview were assessed against ‘The World Class MI Roadmap’ to determine the current state of MI development within CCs. The overall result deduced is that MI development within the CCs is largely limited, informal, and ad hoc in nature and lacks dedicated resources. It is recommended that CCs should work on nurturing MI culture to keep MI activities more active to derive advantages obtainable from the utilization of MI. Further research is needed to explore the development of an MI-based framework to guide the effective utilization of MI by CCs.

Introduction

The construction business environment is highly competitive and volatile. The industry tends to be among the first affected by economic downturns and the last to recover (Tummalapudi, et al., 2021). Unlike many other industries where marketing communication can effectively stimulate demand, CCs struggle to generate demand for their services, except in cases of speculative projects (Mokhtariani, Sebt and Davoudpour, 2017). As project-based entities, CCs rely on actual demand from clients for their business (Setiawan, Erdogana and Ogunlana, 2015). However, clients typically require CC services only once or twice in their lifetime (Drew, 2010), intensifying competition among CCs, compounded by numerous firms offering similar services (Bremer and Kok, 2000). Consequently, the incidence of business failure among CCs is remarkably high (Ogbu, 2018), making survival competition a constant reality and prompting firms to continuously seek innovative strategies to outperform competitors. To remain competitive, CCs must develop strategies aligned with the demands of the external business environment (Plaisance, 2023). Intelligence-gathering plays a crucial role in helping CCs better understand their business environment (Ameer and Othman, 2012). While there is no universally accepted definition for MI due to differing expert perspectives (Safa, et al., 2015), this study aligns with Kotler and Armstrong’s (2017) definition as the systematic gathering and analysis of publicly available information regarding customers, competitors, and market developments. As a result, MI enables CCs to identify business opportunities, optimize bid prices, minimize risks, and enhance client relationships (Mokhtariani, Sebt and Davoudpour, 2017; Asante, et al., 2023).

However, despite the intense competition, market orientation, of which MI is a cornerstone, remains notably low within CCs (Ojo, 2011). Many CCs lack a comprehensive understanding of various marketing strategies, and in some cases, a coherent marketing strategy is absent (Ganah, Pye and Walker, 2008). Consequently, dedicated marketing personnel for MI activities are notably absent within CCs (Jaafar, Aziz and Wai, 2008). Where marketing departments exist, they often focus more on the superficial aspects of marketing rather than substantial action (Cicmil and Nicholson, 1998). Task-oriented paradigm prevalent across the industry impedes the integration of MI into day-to-day operations (Dikmen, Birgonul and Ozcenk, 2005). CCs either do not understand or recognize the true value of MI (Erdis, Coskun and Demirci, 2015). Yet, to meet client expectations, CCs cannot be tardy in implementing intelligence-gathering initiatives (Harrington, Voehl and Wiggin, 2012). Thus, the significance attributed to the marketing concept, including MI, in the construction industry has been on the rise (Erdis, Coskun and Demirci, 2015). Whereas many studies have criticized the extent to which CCs utilize MI to their advantage, other studies (Nicolini, et al., 2000; Mochtar and Arditi, 2001; Dikmen, Birgonul and Ozcenk, 2005) have observed that CCs do utilize MI. Indicating contradictory evidence (Müller-Bloch and Kranz, 2014).

Considering the pivotal role of MI in shaping effective strategy formulation and sustaining a competitive edge within the industry (Stefanikova, Rypakova and Moravcikova, 2015), it becomes crucial to explore how CCs are presently harnessing MI to their benefit. Particularly, when organization-wide generation, dissemination and responsiveness to MI remains a persistent challenge (Gebhardt, Farrelly and Conduit, 2019). Therefore, a key question that arises is: what is the current state of MI development within CCs in Ghana? To the best of our knowledge, little or no study has explored this question particularly, in the context of a sub-Saharan country. Therefore, knowledge gaps persist concerning current MI activities, MI ethical awareness and attitudes toward MI culture development. The objective of this study is to assess the current state of MI development within CCs in Ghana. The significance of this study lies in establishing a baseline understanding of existing MI practices within these companies. This baseline will help identify areas where MI practices are lacking or inefficient. Additionally, it sets the stage for future investigations into developing an MI-based framework to guide the effective utilization of MI. The paper is structured as follows: literature review, research methodology, results, discussion and conclusions.

Theoretical background

MI concept

In business-related intelligence literature, Market Intelligence (MI) has been delineated variously, encompassing terms such as competitive intelligence, marketing intelligence, competitor intelligence, corporate intelligence, strategic intelligence, or customer intelligence (Köseoglu, et al., 2019). These terminological variations arise due to differing conceptualizations of MI by scholars (Calof and Wright, 2008). For instance, some scholars perceive intelligence as a process (Lutz and Bodendorf, 2020), a product (López-Robles, et al., 2019), a function (Maungwa and Fourie, 2018), a system (Cavallo, et al., 2021), a tool (du Toit, 2013), a program (Hedin, Hirvensalo and Vaarnas, 2014), a skill (Markovich, et al., 2019), or a discipline (Barnea, 2020). Furthermore, the terminology used for MI is influenced by the author’s country of origin (Lönnqvist and Pirttimäki, 2006). Additionally, the decision-making context with MI influences its description (Köseoglu Ross and Okumus, 2015). Recent studies (Søilen, 2016; Bisson and Dou, 2017) have revealed that MI and competitive intelligence are predominant terms within business-related intelligence literature due to their practical and substantive similarity (Søilen, 2016). Despite terminological and conceptual differences, there is a consensus that MI furnishes actionable information critical for informed decision-making (McGonagle and Vella, 2012). In this study, we adopt the term MI to encompass all other business-related intelligence concepts, as it is deeply entrenched in the theoretical framework of market orientation (Maltz and Kohli, 1996; Helm, Krinner and Schmalfuß, 2014). As posited by Kohli (2017), the extent of MI gathering by firms is dependent upon their market orientation. Market-oriented firms commonly harness MI, whereas non-market-oriented firms typically do not engage in similar information gathering (Kirca, Jayachandran and Bearden, 2005).

Importance and application of MI

MI plays a crucial role in helping firms understand their competitors’ strengths, weaknesses, strategies, objectives, market positioning and expected behaviours (Bose, 2008). It allows businesses to monitor market dynamics, develop effective marketing strategies, tackle specific marketing challenges and assess market performance (Mehmet, 2008). By leveraging MI, firms can better meet customer needs, foresee new business opportunities and exploit competitors’ weaknesses (Adidam, Banerjee and Shukla, 2012). MI aids in making informed decisions about the marketing mix, including what, why, where and how to market (Navarro-Garcia, Barrera-Barrera and Villarejo-Ramos, 2013). Beyond identifying market opportunities and threats, MI provides deeper insights into competitors, helps prevent competitors from gaining an advantage and supports effective marketing decisions (Li and Li, 2013). Integrating MI into executive information systems enhances customer responsiveness, fosters collaboration and identifies market trends (Yin, 2015). Essentially, MI enables businesses to identify and analyse competitors, mitigate unforeseen events and discover new growth opportunities (He, et al., 2015). According to Köseoglu, Ross and Okumus (2015), MI empowers firms to manage risks, convert knowledge into profit, reduce unnecessary information and secure data for strategic decision-making. It also benefits firms by enabling effective pricing and strategy differentiation (Jamil, Santos and Jamil., 2018). Insights from MI help firms offer desirable services to customers (Mandal, 2018). Recognizing the critical role of MI, the Global Intelligence Alliance has developed ‘The Roadmap for Developing World-class MI,’ (Appendix I) which outlines six key success factors (KSFs) and five stages of MI maturity, ranging from ‘firefighters’ to ‘futurists’ (Hedin, Hirvensalo and Vaarnas, 2014).

Market Intelligence in Construction

In the context of construction, the significance of MI utilization by CCs has long been underscored. For instance, it has been emphasized that a key to successful bidding lies in CCs’ knowledge of their competitors (Moctar and Arditi, 2001). Thus, Soh (2003) accentuated the potential of MI acquisition through interactions with market participants to uncover new opportunities. Langford and Male (2001) highlighted MI’s potential in assisting CCs to identify and capitalize on valuable business prospects. Morgan and Morgan (1991) underscored the importance of structured MI practices, indicating its centrality to CCs’ marketing success. Mochtar and Arditi (2001), in their study, examined the role of MI in CCs’ pricing strategies and found that most CCs gather information conducive to their daily business practices. Dikmen, Birgonul and Ozcenk (2005), in a similar vein, discovered in their study that selecting which international markets to enter necessitates CCs to conduct extensive intelligence-gathering to ascertain their strengths and weaknesses. In a study investigating how quantity surveying firms internationalize their services, Ling and Chan (2008) established that firms excelling in market penetration strategies heavily rely on MI gathering. They further noted that firms predominantly utilize internal sources rather than relying solely on published information. Vuori (2007) identified research institutes, consultancy firms, investment banks and client interactions as various reliable sources of MI in the construction industry. Segarra-Ona, Peiró-Signes and Cervelló-Royo (2015) found that CCs relying on information from suppliers, competitors and clients for innovation are more inclined to orient their innovation towards product or process enhancement, thereby enhancing their competitiveness. Hayes, Sourani and Sertyesilisik (2016) investigated issues of the private finance initiative tendering process and CCs’ bidding strategies, discovering that decisions to bid and the adoption of strategies are largely informed by MI. If confronted with excessive competition or intense competitive pressure, CCs have the option to withdraw from the competition. Such intelligence-gathering enables them to abstain from bidding for projects characterized by intense competition, thereby minimizing resources and time expended on bidding preparations. Demirdöğen and Işik (2019) affirmed that CCs engaging in MI comprehend opportunities and threats, consequently devising strategies accordingly, as they investigated the effects of environmental factors on CCs’ innovation and technology transfer performance. In a study aimed at ascertaining whether elements of MI impacting competitive advantage are pertinent to the construction industry, Somiah, Aigbavboa and Thwala (2020) found that gathering MI enables CCs to identify competitors, industry opportunities and clients’ bargaining power. Ng, et al. (2017) emphasized MI’s strategic value in identifying and evaluating overseas business opportunities. This collective insight underscores the critical importance of intelligence-gathering for effective strategy formulation and the cultivation of sustainable competitive advantage within the industry (Stefanikova, Rypakova and Moravcikova, 2015).

Methodology

Sample Frame

The study population was financial class-one registered members of the Ashanti Region branch of the Association of Building and Civil Engineering Contractors of Ghana (ABCEC), which serves as the umbrella body of indigenous CCs. The Ashanti region is the second largest administrative region in terms of population size and commercial activities is strategically positioned in the middle of the country and is also endowed with major transit and commercial activities after the national capital administrative region of Greater Accra. Regarding the suitability of respondents, the study followed the approach outlined by Calof (2017), where questionnaires are answered by respondents regardless of their familiarity or practice of MI, as the aim was to gain insight into current MI practices within CCs.

Sampling technique and size

Yin (1994) emphasizes the importance of interviewing key informants within an organization to obtain valuable insights and accurate data for research purposes. Purposive sampling techniques were employed to identify 87 CEOs/top managers representing CCs based on two main criteria: 1) the firm had to have been operating for more than ten years (Peters, Subar and Martin, 2019), and 2) they had to be working on a project at the time of the study. Out of the 87 identified CCs meeting the criteria, 56 agreed to participate in the study. This sample size was considered satisfactory based on earlier studies (Groom and David, 2001; Wright, Pickton and Callow, 2002; Priporas, Gatsoris and Zacharias, 2005; Munoz-Canavate and Alves-Albero, 2017), which used similar or smaller sample sizes.

Data collection

For data collection, a simple closed-ended interview was deemed appropriate following similar techniques used by Calof (2017) and Munoz-Canavate and Alves-Albero (2017). This method was efficient in terms of time, minimized subjectivity and bias and facilitated easier coding, comparison and analysis of data (Holloway and Wheeler, 2010). An interview guide, based on previous studies (Priporas, Gatsoris and Zacharias, 2005; Munoz-Canavate and Alves-Albero, 2017), was adapted and divided into four sections: demographics, current MI activities, MI ethical awareness and attitude toward the development of MI culture. The interviews were conducted via phone between May 2023 and December 2023. With prior consent from the interviewees, the interviews were audio-taped. The results were analysed with frequencies and the results were assessed against five KSFs of ‘The World Class MI Roadmap’ to determine the current state of MI development within CCs.

Results

Background of the respondents

Among the fifty-six respondents, 37.5% of the respondents were top management staff and 62.5% were senior management staff. Forty-two-point nine percent had a bachelor’s degree, and 57.1% had a master’s degree. 8.9% had less than ten years of working experience, 55.4% had between ten and twenty years, and 35.7% had more than twenty years. 25% of the respondent’s firms had been in business for between 10 and 20 years, and 75% had been operating for more than twenty years. 51.8% of them said that public entities make up their clientele, while 48.2% reported having both public and private entities in their customer base.

Current MI activities

To gain insight into the current MI practices of CCs, a series of questions were asked. These questions aimed to explore various aspects of MI utilization.

Firms’ experience in intelligence-gathering

Initially, respondents were asked if they had ever undertaken any form of intelligence-gathering. All the firms interviewed acknowledged having engaged in intelligence-gathering activities at some point in the past when asked about their firms’ experience in this area.

Current intelligence-gathering activities

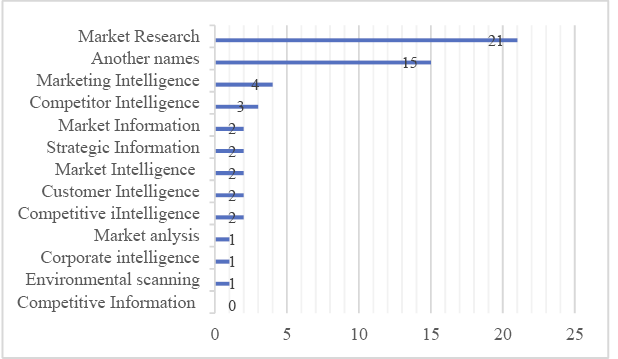

Subsequently, they were asked to specify the most common intelligence-gathering activities they undertook. 100% reported ‘studying project requirements,’ 12.5% mentioned ‘researching competitors,’ and 1.8% indicated ‘investigating client payment history.’ Figure 1 provides a concise overview of these responses.

Figure 1. Current intelligence-gathering activity

Frequency of intelligence-gathering

Regarding the frequency of intelligence-gathering by firms, 57.1% reported doing so sometimes, 33.9% often, and the remaining 9% always.

Focus of intelligence-gathering

In terms of the focus of their intelligence-gathering efforts, 12.5% reported focusing on the pre-project phase, with all respondents (100%) specifying the bidding phase, 7.1% focusing on the delivery phase, and 3.6% on the post-delivery phase.

Name given to intelligence-gathering

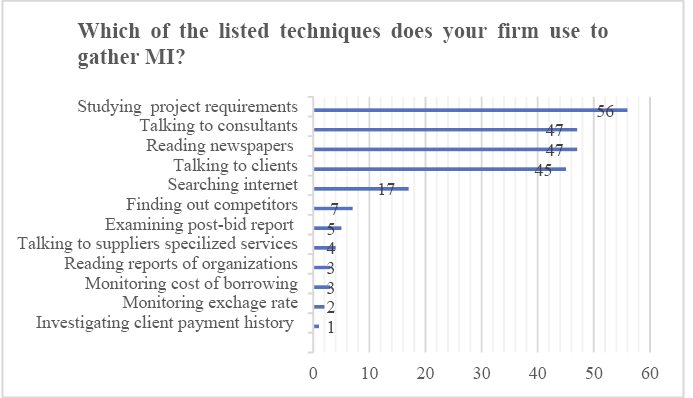

When asked about the terminology used for intelligence-gathering, 37.5% referred to it as ‘market research,’ 7% as ‘market intelligence,’ and 5% as ‘competitive intelligence,’ while 26.7% used other terms. Figure 2 illustrates the terminology preferences indicated by the respondents.

Figure 2. Terms used for intelligence-gathering.

Resource allocation for intelligence-gathering

Furthermore, respondents were questioned about whether their firms designated someone to oversee MI activities, with all respondents (100%) answering ‘NO.’ Similarly, when asked if their firms allocated a specific budget for this activity, again, all respondents (100%) replied ‘NO.’ In terms of the presence of requisite intelligence tools to support their intelligence-gathering efforts, 3.6% stated ‘YES’ and 96.4% responded ‘NO.’

MI ethical awareness

Two questions were posed on this matter. These questions aimed to determine the extent to which CCs are aware of and adhere to ethics in their intelligence-gathering activities.

Use of competitors’ employee

Initially, respondents were asked about the practice of utilizing competitors’ employees to gather information about said competitors. 85.7% did not perceive this approach as unethical, while 14.3% deemed it unethical.

Job interviews

Regarding the use of job interviews as a guise for intelligence-gathering, 71.4% expressed no ethical concerns, 12.5% considered it unethical, and 16.1% were uncertain about its ethical implications.

The Attitude of Contractors toward Improved MI Practices

These questions aimed to assess the firm’s awareness of the importance of a strong MI culture and its commitment to fostering such a culture.

Improving existing MI practices

Regarding the necessity of improving the existing MI practices, 100% of the CCs interviewed agreed with the suggestion for the need for that.

Continuous intelligence-gathering

But when quizzed about the need for continuous intelligence-gathering by their firms, 37.5% said ‘YES,’ 28,5% replied ‘NO,’ and 34% were unsure.

MI Personnel

Regarding the relevance of appointing someone to oversee MI activities, a significant majority, 87.5% expressed support, while a minority of 12.5% remained uncertain.

MI Budget

As for the requirement of allocating a dedicated budget for MI activities, 75.0% favoured the proposal, whereas 12.5% dissented, and 12.5% were undecided.

Discussion

Current MI activities

Currently, there exists some level of awareness of MI among CCs in Ghana, which is very reassuring. This finding confirms the earlier study by Polat and Donmez (2010), which shows that CCs do gather some form of intelligence but largely focus on traditional sources. For instance, most of their intelligence-gathering is concentrated on the bidding phase, indicating a primary focus on winning more bids (Smith, Wright and Pickton, 2010). This is logical, as bidding for construction projects is a strategic move that significantly impacts a CC’s business sustainability within the industry (Jarkas, Mubarak and Kadri, 2014).

It also appears that CCs recognize the limitations of relying solely on experience and intuition for bidding decisions. By emphasizing intelligence-gathering activities, they incorporate insights from market conditions, as argued by Soo and Oo (2014). This shift is reflected in the emphasis on studying project requirements, rated 100% by the CCs when asked about their MI activities. This emphasis is understandable given the well-established knowledge that risks in construction projects frequently lead to time and cost overruns (Thuyet, Ogunlana and Dey, 2007). Furthermore, by investigating project requirements (client needs), CCs can deliver superior service, enhancing customer satisfaction, which is crucial for customer retention in this industry (Othman, 2015).

Regarding the terminology for intelligence-gathering, the findings are consistent with Calof (2017), who noted that organizations brand their intelligence activities differently. Notably, among the thirteen names suggested, 37.5% of the CCs referred to ‘market research’ as the generic term for intelligence activities. As Köseoglu, Ross and Okumus (2015) indicated, the variance in terms is linked to the specific purposes for which intelligence is gathered. Consequently, the name chosen by the CCs may have influenced why only 9% consistently engage in intelligence-gathering. Market research focuses on a specific marketing strategy while MI has a broader focus on understanding market opportunities and threats, facilitating well-informed decision-making (Inha and Bohlin, 2018).

Insights into resource allocation for MI activities revealed a consistent pattern across all CCs. Admittedly, having someone responsible for MI activity is the first step toward establishing an intelligence-oriented organization (Hedin, Hirvensalo and Vaarnas, 2014). Firms with departments for MI are more likely to utilize it effectively (Hattula, et al., 2015). The number of marketing staff is an indicator of the importance CCs attach to marketing efforts (Polat and Donmez, 2010). MI cannot offer answers if the right personnel are not in place to manage these activities. Until the right person(s) is in place to lead MI activities, its full potential will not be reached (Priporas, Gatsoris and Zacharias, 2005). Yet, the results found that none of the firms had a designated person in charge of MI. This finding confirms Jaafar, Aziz and Wai’s (2008) observation of a lack of dedicated personnel for marketing activities within CCs, corroborating the argument that many CCs do not pay sufficient attention to marketing activities (Nobre and Faria, 2017).

Firms with dedicated budgets for MI activities are more effective in exploring different sources for MI collection and techniques (Cacciolatti and Fearne, 2013). Similarly, none of the firms have a budget for MI activities indicating a potential missed opportunity for optimizing their intelligence-gathering. While intelligence-gathering tools would help CCs easily search for necessary information and ensure successful intelligence-gathering activities (Hedin, Hirvensalo and Vaarnas, 2014), currently, the CCs do not have dedicated software to support organizing and managing the intelligence process as a searchable database of structured and relevant information. The results indicate a potential lack of recognition within CCs regarding the fundamental value of MI initiatives (Erdis, Coskun and Demirci, 2015). Another contributing factor could be a prevailing perception within CCs that MI capabilities do not constitute a substantial source of competitive advantage (Dikmen, Birgonul and Ozcenk, 2005). They may be unaware that consistent investment in marketing results in improved competitive advantage (Srinivasan, Rangaswamy and Lilien, 2005). This affirms the finding that intelligence-gathering activities within CCs are often conducted in an ad hoc manner without coordination (Morgan and Morgan, 1991). Earlier findings show that instead of the marketing function being seen as complementary, it is often relegated to the background (Cicmil and Nicholson, 1998).

MI ethical awareness

Despite repeated emphasis on the feasibility of ethical intelligence-gathering (Nasri, 2011), some firms still resort to unethical methods for collecting MI. Therefore, when asked whether it is ethical for a firm to use its competitor’s employees to obtain information about the competitors, the overwhelming majority (85.7) did not consider such practices unethical, while few deemed it unethical. On the use of job interviews as a pretext to gather MI about competitors, the majority of 71.4% did not see anything unethical about that, while the rest deemed either unethical or were unsure. The results confirm a recent study by Chan, Chan and Au (2020), that some firms persist in using questionable intelligence-gathering techniques, such as using competitors’ employees to obtain information about the competitors. These results are an indication that CCs might not be aware of the differences between MI and business espionage (Crane, 2005). They might be also unaware that 90% of the information they require to understand their markets and competitors and make critical decisions is already available to the public (Yin, 2015). In the context of construction, project pressures such as low profit and intense competition which lead to unethical contractor behaviour (Liu, Zhao and Li, 2017), could be accountable for resorting to such questionable intelligence-gathering techniques.

Attitudes Toward Improved MI Practices

Considering that for any firm to be successful in its MI activities, certain requirements must be fulfilled (Helm, Krinner and Schmalfuß, 2014), there was a need to understand how the CCs are willing to put measures in place to enable them to obtain the ultimate benefits of MI utilization. Therefore, four questions were asked concerning this issue. First, they all believed that current practices need to be improved. However, there was a split in the opinion on the need for regular intelligence-gathering. While 37.5% accepted the need for continuous intelligence-gathering, 28,5% did not see the reason for that, and 34% were unsure of continuous or ad hoc intelligence-gathering. Notably, none of the firms rejected the idea of having someone responsible for MI activities within their firms considering the many benefits of MI. So, about 88% believed that having someone in charge of MI activities would improve the current practices. This finding aligns with the literature that assigning specific staff to oversee MI activities can help the organization identify the right information and sources that are most relevant to decision-making (Cacciolatti and Fearne, 2013). As explained by Priporas, Gatsoris and Zacharias (2005), designating somebody to oversee the MI function is necessary for the effective implementation of an MI system, as the system itself does not provide answers. On the need for budgetary support for MI activities, the majority of 75.0% endorsed the idea, corroborating Cacciolatti and Fearne’s (2013) account that committing sufficient financial resources to the MI function empowers firms to better identify their information needs compared to companies without dedicated resources. The favourable attitude towards MI activities suggests that CCs may have realized they need for new and distinct skill set to set themselves apart from competitors. The findings are in line with the indications that the MI function is being recognized as an important function in organizations compared to other support functions (Hedin, Hirvensalo and Vaarnas, 2014).

Current State of Market Intelligence Development

To determine the current state of MI development within CCs, five KSFs drawn from ‘The World Class MI Roadmap’ were assessed: scope, process, tools, organization, and culture, based on the responses provided. Regarding the MI scope, which measures the focus of intelligence activities, 12.5% focused on the pre-project phase, 100% on the bidding phase, 7.1% on the delivery phase, and 3.6% on the post-delivery phase. This indicates that the current MI has a limited scope and is largely focused on the bidding phase. The MI process assesses the frequency at which firms gather intelligence; 57.1% reported doing so occasionally, 33.9% often, and the remaining 9% continually. This further indicates that the current MI tends to be a reactive, ad hoc process that addresses issues as they emerge. Regarding MI tools, which assess the availability of dedicated intelligence software, only 3.6% reported availability, while 96.4% indicated non-availability. This suggests that CCs are in the informal firefighting stage. In terms of MI organization, which evaluates how various resources are integrated to facilitate the intelligence process, currently, there are no resources specifically allocated to MI, indicating that CCs are conducting MI activities in a non-structured manner. Concerning MI culture, which analyses the mechanisms within CCs aimed at ensuring the sustained efficacy of intelligence-gathering, there is some awareness of MI, but the organizational culture overall is still neutral towards MI as there are no supporting structures in place.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study assessed the current state of MI development within CCs in Ghana against the recognition that MI forms the bedrock of the marketing concept, serving as a vital component in market-oriented strategic planning and execution. However, despite extensive research on MI in various industries and countries, there remains a notable scarcity of studies on MI within Ghana’s construction sector. The findings reveal that CCs do engage in MI activities, albeit with a significant reliance on traditional sources. Presently, their MI focus predominantly centers around securing bids, with comparatively less attention given to maintaining client relationships. Undesirably, CCs do not allocate sufficient resources to MI activities. The CCs are either unaware of unethical intelligence-gathering techniques, or they are not hesitant to employ such methods to acquire MI. Despite the absence of dedicated resources, CCs exhibit a positive attitude toward enhancing existing MI practices. The current MI development stage within Ghanaian CCs can be described as the ‘firefighters’ stage of MI maturity. The overall result deduced is that MI development within the CCs is largely limited, informal, and ad hoc in nature and lacks dedicated resources. This implies that current MI activities are conducted without dedicated resources, primarily on an extempore basis with minimal coordination. While the investigation primarily focused on CCs in a specific administrative region of Ghana, the insights gained serve as a reference point for CCs in other developing countries, or even developed countries. Given the myriad advantages associated with MI, it is recommended that CCs recognize MI as a strategic and complementary function to core activities of CCs like engineering and estimating, thereby investing in its development. They should transition from reactive intelligence-gathering to proactive intelligence-gathering, which aligns with the core of MI. Reactive intelligence-gathering typically involves responding to immediate needs or issues as they arise, which may limit the company’s ability to anticipate market shifts or capitalize on emerging opportunities. In contrast, proactive intelligence-gathering involves systematically collecting, analysing, and interpreting information to anticipate market trends, competitor actions, and customer preferences. This proactive approach empowers CCs to stay ahead of the curve, make informed decisions, and adapt their strategies accordingly.

Implications and future studies

The findings highlight the need for industry-wide standards and best practices for MI activities. Sharing best practices and benchmarking against more mature MI practices from other industries can help CCs in Ghana and similar contexts improve their MI capabilities and achieve better business outcomes. Future research should delve into the specific information monitored by CCs for MI analysis. Another study could explore the possibility of developing indicators to assess the effectiveness of MI utilization by CCs. Moreover, future studies could explore the development of an MI-based framework to guide the effective utilization of MI by CCs.

Acknowledgment

This paper forms part of a large research project entitled ‘Utilising Market Intelligence for Improving the Competitiveness of Construction Firms’ from which other papers have been produced with different objectives/scopes but share a similar background and methodology.

References

Adidam, P.T., Banerjee, M. and Shukla, P., 2012. Competitive intelligence and firm’s performance in emerging markets: an exploratory study in India. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 27(3), pp.242–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858621211207252

Ameer, R. and Othman, R., 2012. Sustainability practices and corporate financial performance: A study based on the top global corporations. Journal of Business Ethics, 108, pp.61-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1063-y

Asante, J., Badu, E., Kissi, E., Adjei-Kumi, T. and Abu, M.A.I., 2022. Establishing the need for utilizing market intelligence by local construction firms in developing countries. In: Aigbavboa, C., Thwala, W.D. and Aghimien, D.O., eds. Towards a Sustainable Construction Industry: The Role of Innovation and Digitalization. pp.589–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22434-8_57

Barnea, A., 2020. Strategic intelligence: a concentrated and diffused intelligence model. Intelligence and National Security, 35, pp.701-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2020.1747004

Bisson, C. and Dou, H., 2017. Une Intelligence Economique et Stratégique pour les PME, PMI et ETI en France. Vie and Sciences de l’Entreprise, 2(204), pp.164-79. https://doi.org/10.3917/vse.204.0164

Bose, R., 2008. Competitive intelligence process and tools for intelligence analysis. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 108(4), pp.510-28. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570810868362

Bremer, W. and Kok, K., 2000. The Dutch construction industry: a combination of competition and corporatism. Building Research and Information, 28(2), pp.98-108. https://doi.org/10.1080/096132100369000

Cacciolatti, L. and Fearne, A., 2013. Marketing intelligence in SMEs: implications for the industry and policymakers. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 31(1), pp.4-26. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501311292894

Calof, J., 2017. Canadian competitive intelligence practices – a study of practicing strategic and competitive intelligence professionals’ Canadian members. Foresight, 19(6), pp.577-89. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-07-2017-0024

Calof, J.L. and Wright, S., 2008. Competitive intelligence: A practitioner, academic and inter-disciplinary perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 42(7/8), pp.717–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560810877114

Cavallo, A., Sanasi, S., Ghezzi, A. and Rangone, A., 2021. Competitive intelligence and strategy formulation: connecting the dots. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 31(2), pp.250-72. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-01-2020-0009

Chan, P., Chan, J. and Au, A.K.M., 2020. Are hotel managers taught to be aggressive in intelligence-gathering? Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 9, pp.417–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-020-00117-4

Cicmil, S. and Nicholson, A., 1998. The role of the marketing function in operations of a construction enterprise: misconceptions and paradigms. Management Decision, 36(2), pp.96-101. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251749810204179

Crane, A., 2005. In the company of spies: When competitive intelligence-gathering becomes industrial espionage. Business Horizons, 48, pp.233-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2004.11.005

Demirdöğen, G. and Işik, Z., 2019. Environmental scanning approach to assess innovation and technology. Technology and Investment, 10, pp.1-21.

Dikmen, R., Birgonul, M.T. and Ozcenk, I., 2005. Marketing orientation in construction firms: evidence from Turkish contractors. Building and Environment, 40, pp.257-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.07.009

Drew, D.S., 2010. Competing in construction auctions: A theoretical perspective. In: Gerard de Valence, ed. Modern Construction Economics. 1st ed. UK: Routledge.

du Toit, A.S., 2013. Comparative study of competitive intelligence practices between two retail banks in Brazil and South Africa. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 3, pp.30-39. https://doi.org/10.37380/jisib.v3i2.67

Erdis, E., Coskun, H. and Demirci, M., 2015. Perceptions of Turkish construction firms about the marketing concepts. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 21(3), pp.423-40. https://doi.org/10.3846/20294913.2014.958878

Ganah, A., Pye, A. and Walker, C., 2008. Marketing in construction: Opportunities and challenges for SMEs. In: COBRA 2008, 4-5 September 2008, Dublin, Ireland.

Gebhardt, F.F., Farrelly, F.J. and Conduit, J., 2019. Market intelligence dissemination practices. Journal of Marketing, [e-journal] pp.1-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919830958

Groom, R.J. and David, R.F., 2001. Competitive intelligence activity among small firms. Advanced Management Journal, 66(1), pp.12-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/cir.1014

Harrington, H.J., Voehl, F. and Wiggin, H., 2012. Applying TQM to the construction industry. The TQM Journal, 24(4), pp.352-62. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731211247373

Hattula, J.D., Schmitz, C., Schmidt, M. and Reinecke, S., 2015. Is more always better? An investigation into the relationship between marketing influence and managers’ market intelligence dissemination. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 32(2), pp.179-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2015.02.001

Hayes, L., Sourani, A. and Sertyesilisik, B., 2016. An investigation into the improvement of tendering processes and the level of competition for PFI construction projects. The Journal of Modern Project Management, 4(1), pp.94-103.

He, W., Shen, J., Tian, X., Li, Y., Akula, V., Yan, G. and Tao, R., 2015. Gaining competitive intelligence from social media data: Evidence from two largest retail chains in the world. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 115(9), pp.1622-36. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-03-2015-0098

Hedin, H., Hirvensalo, I. and Vaarnas, M., 2014. The Handbook of Market Intelligence: Understand, Compete and Grow in Global Markets. 2nd ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Helm, R., Krinner, S. and Schmalfuß, M., 2014. Conceptualization and integration of marketing intelligence: The case of an industrial manufacturer. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 21(4), pp.237-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051712X.2014.979587

Holloway, I. and Wheeler, S., 2010. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Inha, E. and Bohlin, S., 2018. Market Intelligence: a Literature Review Dissertation [pdf]. Available at: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hh:diva-33419.

Jaafar, M., Aziz, A.R.A. and Wai, A.L.S., 2008. Marketing practices of professional engineering consulting firms: Implement or not to implement? Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 14(3), pp.199-206. https://doi.org/10.3846/1392-3730.2008.14.17

Jamil, G.L., Santos, L.R.D. and Jamil, C.C., 2018. Improving competitiveness through organizational market intelligence. In: Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, 4th ed., pp.961-70. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2255-3.ch083

Jarkas, A.M., Mubarak, S.A. and Kadri, C.Y., 2014. Critical factors determining bid/no bid decisions of contractors in Qatar. Journal of Management in Engineering, 30(4), pp.1-11. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000223

Kirca, H.A., Jayachandran, S. and Bearden, W.O., 2005. Market orientation: A meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), pp.24-41. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.2.24.60761

Kohli, A.J., 2017. Market orientation in a digital world. Global Business Review, 18(3), pp.1-3. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150917700769

Köseoglu, M.A., Morvillo, A., Altin, M., De Martino, M. and Okumus, F., 2019. Competitive intelligence in hospitality and tourism: A perspective article. Journal of Strategic and International Studies, 75(1), pp.239-42. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2019-0224

Köseoglu, M.A., Ross, G. and Okumus, F., 2015. Competitive intelligence practices in hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, pp.161-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.11.002

Kotler, P. and Armstrong, G., 2017. Principles of Marketing. 17th ed. London: Pearson.

Langford, D. and Male, S., 2001. Strategic Management in Construction. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470690291

Li, Y.M. and Li, T.Y., 2013. Deriving market intelligence from microblogs. Decision Support Systems, 55(1), pp.206-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2013.01.023

Ling, F.Y.Y. and Chan, A.H.M., 2008. Internationalizing quantity surveying services. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 15(5), pp.440-55. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699980810902730

Liu, J., Zhao, X. and Li, Y., 2017. Exploring the factors inducing contractors’ unethical behavior: Case of China. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 143(3), pp.1-10. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000316

Lönnqvist, A. and Pirttimäki, V., 2006. The measurement of business intelligence. Information Systems Management, 23(1), pp.32-40. https://doi.org/10.1201/1078.10580530/45769.23.1.20061201/91770.4

López-Robles, J.R., Otegi-Olasoa, J.R., Gómez, I.P. and Cobo, M.J., 2019. 30 years of intelligence models in management and business: A bibliometric review. International Journal of Information Management, 48, pp.22-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.013

Lutz, C.J. and Bodendorf, F., 2020. Analyzing industry stakeholders using open-source competitive intelligence – a case study in the automotive supply industry. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 33(3), pp.579-99. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-08-2019-0234

Maltz, E. and Kohli, A.K., 1996. Market intelligence dissemination across functional boundaries. Journal of Marketing Research, 33(1), pp.47-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379603300105

Mandal, P.C., 2018. Marketing information and marketing intelligence: Roles in generating customer insights. International Journal of Business Forecasting and Marketing Intelligence, 4(3), pp.311-21. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBFMI.2018.092786

Markovich, A., Efrat, K., Raban, D.R. and Souchon, A.L., 2019. Competitive intelligence embeddedness: Drivers and performance consequences. European Management Journal, 37, pp.708-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.04.003

Maungwa, T. and Fourie, I., 2018. Competitive intelligence failures: An information behavior lens to key intelligence and information needs. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 70(4), pp.367-89. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2018-0018

McGonagle, J.J. and Vella, C.M., 2012. Proactive Intelligence: The Successful Executive’s Guide to Intelligence. London: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2742-0

Mehmet, H.K., 2008. Determinants of export marketing research in Turkish companies. Journal of Euromarketing, 17(2), pp.95-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496480802134696

Mochtar, K. and Arditi, D., 2001. Role of marketing intelligence in making pricing policy in construction. Journal of Management in Engineering, 17(3), pp.140–48. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(2001)17:3(140)

Mokhtariani, M., Sebt, M.H. and Davoudpour, H., 2017. Construction marketing: Developing a reference framework. Advances in Civil Engineering. [e-journal] 2017(4), pp.1-14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7548905

Morgan, R.E. and Morgan, N.A., 1991. An appraisal of the marketing development in engineering consultancy firms. Construction Management and Economics, 9(4), pp.355-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446199100000028

Müller-Bloch, C. and Kranz, J., 2014. A framework for rigorously identifying research gaps in qualitative literature reviews. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Information Systems - Exploring the Information Frontier, ICIS 2015. December 13-16, 2015, Fort Worth, Texas, USA. https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2015/proceedings/ResearchMethods/2.

Muñoz-Cañavate, A. and Alves-Albero, P., 2017. Competitive intelligence in Spain: A study of a sample of firms. Business Information Review, 34(4), pp.194-204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266382117735982

Nasri, W., 2011. Competitive intelligence in Tunisian companies. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 24(1), pp.53-67. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410391111097429

Navarro-García, A., Barrera-Barrera, R. and Villarejo-Ramos, A.F., 2013. The importance of market intelligence in Spanish firms’ exporting activity. ESIC Market Economics and Business Journal, 44(3), pp.9-31. https://doi.org/10.7200/esicm.146.0443.1

Ng, T.N., Wong, J.M.W., Chiang, Y.H. and Lam, P.T., 2017. Improving the competitive advantages of construction firms in developed countries. ICE Proceedings Municipal Engineer, 171(4), pp.1-11. https://doi.org/10.1680/jmuen.17.00002

Nicolini, D., Tomkins, C., Holti, R., Oldman, A. and Smalley, M., 2000. Can target costing and whole life costing be applied in the construction industry? Evidence from two case studies. British Journal of Management, 11(4), pp.303–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00175

Nobre, H. and Faria, J., 2017. Exploring marketing strategies in architectural services: The case of the architecture firms in Portugal. International Journal of Business Excellence, 12(3), pp.275-87. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEX.2017.084438

Ogbu, P.C., 2018. Survival practices of indigenous construction firms in Nigeria. International Journal of Construction Management, 18(1), pp.78-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2016.1277056

Ojo, G.K., 2011. Effective marketing strategies and the Nigerian construction professionals. African Journal of Marketing Management, 3(12), pp.303-11.

Othman, A.E., 2015. An international index for customer satisfaction in the construction industry. International Journal of Construction Management, 15(1), pp.33–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2015.1012140

Peters, E., Subar, K. and Martin, H., 2019. Late payment and nonpayment within the construction industry: Causes, effects and solutions. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 11(3), pp.1-12. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000314

Plaisance, G., 2023. Which stakeholder matters: Overall performance and contingency in nonprofit organizations. International Studies of Management and Organization, 53(3), pp.125-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2023.2237388

Polat, G. and Donmez, U., 2010. Marketing management functions of construction companies: evidence from Turkish contractors. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 16(2), pp.267–77. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2010.31

Priporas, C.V., Gatsoris, L. and Zacharias, V., 2005. Competitive intelligence activity: evidence from Greece. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 23(7), pp.659-69. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500510630195

Safa, M., Shahi, A., Haas, C.T., Fiander-McCann, D., Safa, M., Hipel, K. and MacGillivray, S., 2015. Competitive intelligence (CI) for evaluation of construction contractors. Automation in Construction, 59, pp. 49-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2015.02.009

Segarra-Oña, M., Peiró-Signes, A. and Cervelló-Royo, R., 2015. A framework to move forward on the path to eco-innovation in the construction industry: implications to improve firms’ sustainable orientation. Science and Engineering Ethics, 21, pp.1469–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-014-9620-2

Setiawan, H., Erdogana, B.H. and Ogunlana, O.S., 2015. Competitive aggressiveness of contractors: A study of Indonesia. Procedia Engineering, 125, pp.68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.11.011

Smith, J.R., Wright, R. and Pickton, D., 2010. Competitive intelligence programs for SMEs in France: evidence of changing attitudes. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 18(7), pp.523-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2010.529154

Soh, P.H., 2003. The role of networking alliances in information acquisition and its implications for new product performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, pp.727–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00026-0

Søilen, K.S., 2016. A research agenda for intelligence studies in business. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 5(1), pp.21-36.

Somiah, M.K., Aigbavboa, C.O. and Thwala, W.D., 2020. Validating elements of competitive intelligence for competitive advantage of construction firms in Ghana: A Delphi study. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 13(3), pp.377–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2020.1762309

Soo, A. and Oo, B.L, 2014. The effect of construction demand on contract auctions: an experiment. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 21(3), pp.276-90. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-01-2013-0010

Srinivasan, R., Rangaswamy, A. and Lilien, G., 2005. Turning adversity into advantage: Does proactive marketing during a recession pay off? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 22(2), pp.109-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2004.05.002

Stefanikova, L., Rypakova, M. and Moravcikova, K., 2015. The impact of competitive intelligence on sustainable growth of the enterprises. Procedia Economics and Finance, 26, pp.209–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00816-3

Thuyet, N., Ogunlana, S. and Dey, P.K., 2007. Risk management in oil and gas construction projects in Vietnam. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 1(2), pp.175-94. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506220710761582

Tummalapudi, M., Killingsworth, J., Harper, C. and Mehaney, M., 2021. US construction industry managerial strategies for economic recession and recovery: A Delphi study. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 147(11), pp.04021146. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002175

Vuori, V., 2007. Business intelligence activities in construction companies in Finland – A series of case studies. In: 8th European Conference on Knowledge Management, 6-7 September 2007, Barcelona, Spain. pp.1086-92.

Wright, S., Pickton, W.D. and Callow, J., 2002. Competitive intelligence in UK firms: a typology. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 20(6), pp.349-60. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500210445400

Yin, C.H., 2015. Measuring organizational impacts by integrating competitive intelligence into an executive information system. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 29, pp.533–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-015-1135-4

Yin, R.K., 1994. Case Study Research, Design and Methods. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications.