Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 23, No. 3/4

December 2023

RESEARCH ARTICLE

A Constructive System to Assess the Performance-based Grading of Construction Labour through Work-Based Training Components and Applications

Kesavan Manoharan1,*, Pujitha Dissanayake2, Chintha Pathirana2, Dharsana Deegahawature3, Renuka Silva4

1 Department of Construction Technology, Faculty of Technology, Wayamba University of Sri Lanka, Kuliyapitiya, Sri Lanka

2 Department of Civil Engineering, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

3 Department of Industrial Management, Wayamba University of Sri Lanka, Kuliyapitiya, Sri Lanka

4 Centre for Quality Assurance, Wayamba University of Sri Lanka, Kuliyapitiya, Sri Lanka

Corresponding author: Kesavan Manoharan, Department of Construction Technology, Faculty of Technology, Wayamba University of Sri Lanka, Kuliyapitiya, Sri Lanka, kesavan@wyb.ac.lk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v23i3/4.8779

Article History: Received 01/10/2022; Revised 24/06/2023; Accepted 23/08/2023; Published 23/12/2023

Abstract

Various industry sectors of many developing countries have been facing various challenges associated with low performance of labour due to poor work-based training practices. This study aims to assess the performance of labour in construction by applying systematic work-based training components. A comprehensive study methodology was adopted through literature reviews and experts’ interviews/discussions, with problem-focused and action-oriented communication approaches to develop effective tools, systems and practices related to labour training elements and performance assessments within a framework. Through a new construction supervisory training programme, the developed practices were applied to 200-300 labourers working on 23 construction projects in Sri Lanka. The results show the detailed patterns of the significant changes in labour performance with the quantified values. Overall quantitative values indicate a nearly 60% increase in the performance of labour within six months of the training period compared to the starting point. A considerable level of performance improvement was reported in the soft skills (90%) and material handling abilities (70%) of labourers. A moderate level of performance improvement was identified in other competency elements related to the application of basic science/technology-related practices (55%), simple engineering/technology-related practices (44%), construction methods and technology (56%), green practices (36%) and fundamental management aspects (34%). The overall performance values of labourers employed in road/bridge projects were found to be noticeably lower compared to the labourers who worked on other types of projects. The results further describe the well-improved theoretical knowledge and operational skills of the trained labourers, which has uplifted their job standards from working under close supervision to working under general supervision with some autonomy. Moreover, the study findings contribute to controlling the excessive inclination of local firms toward foreign labour by unlocking the potential barriers to expanding the local labour supply with lifelong learning and career benefits/opportunities for labourers. The findings will have a significant impact on how other developing nations and industries must manage their labour to obtain higher work efficiency in the foreseeable future.

Keywords

Competence Development; Construction Supervision; Labour Training; Performance Evaluation; Worker Grading

Introduction

The construction industry is a labour-intensive industry that relies heavily on labour performance (Fernando, Fernando, and Gunarathna, 2016). Labour is the most valuable asset in the construction industry since it plays a central role in processing various operations connected with other resources (Ghate and Minde, 2016), where labour costs contribute between 30-50% of total project costs in a typical construction project (Shoar and Banaitis, 2019). Improvement in labour performance is the major component for successful completion of construction projects (Mistri, Patel and Pitroda, 2019). But the construction sector in many developing countries is confronted with difficulties related to labour performance (Dinh and Nguyen, 2019).

The performance of labour plays a major part in the efficiencies of construction firms (Murari and Joshi, 2019). It is a key element in the adaptation of industries to the opportunities and challenges of globalisation and the next industrial revolution (Mistri, Patel and Pitroda, 2019). Studies reveal that job-related labour skills are the major driver of labour performance (Mojahed and Aghazadeh, 2008; Manoharan, et al., 2021a). While Sangole and Ranit (2015) suggest that educational and cultural backgrounds of labour vary in a wide spectrum and influence labour performance in construction, Mistri, Patel and Pitroda (2019) state that the performance levels vary among labourers due to economic, social, physical and psychological factors.

Education and training play a key role in improving the performance and work qualities of labour (Sangole and Ranit, 2015; Manoharan, et al., 2020, 2021a). However, other studies report that the structural issues of the vocational education sector and the inadequate labour training facilities among construction firms have been the major reasons for the construction industry experiencing the low performance of construction operations in many countries (Onyekachi, 2018; Mistri, Patel and Pitroda, 2019; Manoharan, et al., 2020). Studies further highlight the need to act against the unavailability of proper labour performance evaluation systems in many developing countries (Onyekachi, 2018; Manoharan, et al., 2021a).

Sri Lankan Context

Considering the Sri Lankan context, the post-war era has attracted the government’s attention as well as the private sector on the infrastructure development of the country (TVEC, 2017). The construction industry expansion has created great opportunities and various challenges in the country (Manoharan, et al., 2020). But recent studies report the failure of many local construction firms in the Sri Lankan construction industry due to poor performance of Sri Lankan labour. The low performance of labour has led the construction industry to face various challenges related to cost overruns, time overruns and quality-related problems, affecting the overall performance of numerous construction projects in Sri Lanka, similar to the scenario in many other developing countries (Dinh and Nguyen, 2019; Manoharan, et al., 2020). This has resulted in the growth of foreign labour in the Sri Lankan construction sector, whereas unemployment has been on the rise among the local community, significantly influencing the country’s economy (TVEC, 2017; Silva, Warnakulasuriya and Arachchige, 2018). Studies highlight the significant differences in cognitive and self-management skills of Sri Lankan labour compared with the leading foreign labour who occupy job opportunities in Sri Lanka (Silva, Warnakulasuriya and Arachchige, 2018; Manoharan, et al., 2021a). The quality of trained people from Sri Lankan training institutions is not up to the industry’s expectations, and this has resulted in skill shortage as one of the notable factors that yield high impacts on the performance of labour (Fernando, Fernando, and Gunarathna, 2016; Silva, Warnakulasuriya and Arachchige, 2018; Manoharan, et al., 2021a). The industry’s requirements are not properly addressed in school curricula or vocational training programmes in the country (Fernando, Fernando, and Gunarathna, 2016; TVEC, 2017; Manoharan, et al., 2020). Recent studies further highlight the absence of systematic procedures/mechanisms among most Sri Lankan construction firms for the delivery of work-based labour training facilities, evaluation of labour skills and performance assessments and productivity measurements at worksites (TVEC, 2017; Silva, Warnakulasuriya and Arachchige, 2018; Manoharan, et al., 2020). Similar requirements also need to be addressed by the construction sector in many other developing countries (Onyekachi, 2018; Dinh and Nguyen, 2019; Mistri, Patel and Pitroda, 2019; Shoar and Banaitis, 2019). The current study has discovered a dearth of empirical studies that systematically addressed these needs and gaps.

Importance of the Study

The background investigation of this study highlights the importance of improving the labour competencies through effective training practices for achieving higher performance in labour operations. Based on the above-stated needs, this study aims to assess the performance of labour by applying effective training and performance evaluation practices at construction sites. Accordingly, the study objectives mainly focused on quantifying the labour performance in different competency element categories, applying performance-based grading approaches in planning labour resources as well as comparing the changes in the performance levels and grading considering different competency factors and types of project characteristics. This may provide proactive practices in construction planning and operational management systems associated with organisational policies to upgrade the job standards of labourers as well as to achieve organisational goals with higher productivity, profitability and other sustainability-related benefits.

Training Elements and Performance Evaluations for Construction Labourers

Ojha, et al. (2020) assessed the training delivery methods and evaluation techniques in health and safety training practices among construction workers. Their results indicate a lack of focus on work-based training methods among the firms, where most have been using traditional methods, which are usually lecture-based sessions and toolbox talks. Studies highlight that work-based training methods have a considerable advantage over traditional methods and result in a significant increase in the cognitive, transferable and self-management skills of construction workers (Siregar, 2017; Gao, Gonzalez and Yiu, 2019).

Siregar (2017) focused on assessing work-based learning activities in a training programme conducted on concrete works among 30 construction workers in Medan City, Indonesia. A gradual improvement in the competencies of trainees throughout the work-based training delivery was reported, even though the study observed poor involvement in work-based training tasks among the trainees at the beginning stage. Siregar (2017) recommends assessing the competencies of trainees considering the following learning domains in work-based training tasks.

• Noting explanation of instructor; Asking questions; Showing self-confidence; Communicating and participating in group tasks; Sharing ideas/opinions among others; Receiving the opinions/inputs of others; Responding to the opinions of others; Paying attention to fellow members of other groups; Making a summary of the learning contents.

Ojha, et al. (2020) show that the competencies of trainees are assessed by most firms using questionnaire surveys, which results in inadequate learning outcomes. With the focus on promoting the workers’ interaction and situational awareness in the competency assessments, digital environments were developed by a few studies using various technologies such as virtual reality gaming technology (Dickinson, et al., 2018), 360-degree panorama technology (Pham, et al., 2018). The effectiveness of using photography and videography techniques was emphasised by Dickinson, et al. (2018) to generate real surrounding views of the construction environment for training assessment purposes. But, Ojha, et al. (2020) highlight the requirements of technological advancement and high costs for the usage of these digital technologies, as the major reason for the training sectors in many developing countries not adapting their current practices to the digital environment.

Though a few studies recommend some practices for training delivery and assessing competencies, there has been a scarcity of systematic training guide models and performance evaluation systems for the construction industry. The literature review of this study highlights the significance of the construction labour training guide model presented by Manoharan, et al. (2021a) and the labour performance score and grading systems introduced by Manoharan, et al. (2022), which can be very useful tools for developing training elements for effective delivery of training components and performance evaluations for labourers in construction. With the direct scope of improving labour performance and productivity levels, the labour training guide model of Manoharan, et al. (2021a) consists of a set of well-developed labour training exercises (LBEXs) that can be systematically delivered to the construction labourers by construction supervisors. The application of the Manoharan, et al. (2021a) training guide model is limited to developing training practices for the construction labourers whose levels of competencies vary between the stages of unskilled and master craftsperson. Based on the aims of each LBEX, labour training elements of outcomes (LBEOs) were developed by Manoharan, et al. (2022), where the LBEOs allow the trainers to assess the competencies of labourers within a systematic framework. Importantly, these LBEXs and LBEOs cover the common elements that can be applied in all types of construction projects. The relative weights of LBEXs and LBEOs were also presented by Manoharan, et al. (2021a) and Manoharan, et al. (2022), respectively (as shown in Table 1). These allow the construction supervisors to understand how much importance needs to be considered for a specific labour task compared to other ones. Based on the relative weights of LBEXs and LBEOs and the competency assessments of labourers, a labour performance score (LBPS) system and a labour grading scheme (LGS) were comprehensively developed by Manoharan, et al. (2022) for evaluating the performance of labour within a systematic framework. Their proposed systems include a comprehensive procedure to undertake labour performance measurements and labour grading that allow the construction project team to effectively plan the crew mixes for different tasks. These can also be very helpful for employers to make rational decisions on job promotions, salary increments and layoff situations by considering the performance of each labourer.

| Exercise Code Nos. and Aims/Objectives [Relative Weights] (Manoharan, et al., 2021a) | Labour Training Elements of Outcomes (LBEOs) [Relative Weights] (Manoharan, et al., 2022) | |

|---|---|---|

| LBEX1: Improving the soft skills of labourers required in the construction works [0.23] | LBEO1.1: | Labourers perform activities with the required work-related transferable skills at construction sites (Learning; Reading, writing and listening; Leadership; Teamwork; Communication; Memorisation; Innovative thinking; Analytical skills and abilities) [0.4] |

| LBEO1.2: | Labourers perform activities with the required work-related self-management at construction sites (Adapting changes in new environments; Critical reasoning; Problem solving; Decision making; Psychology; Reduction of alcohol and drugs usage; Commitment; Self-motivation; Punctuality) [0.6] | |

| LBEX2: Improving the performance of labourers on understanding and application of basic science and technology related practices [0.10] | LBEO2.1: | Labourers assist with the tasks related to measurements and estimation in the construction [0.6] |

| LBEO2.2: | Labourers carry out labour works with a proper understanding of construction drawings [0.3] | |

| LBEO2.3: | Labourers use appropriate ICT applications for easy work operations [0.1] | |

| LBEX3: Improving the performance of labourers on an understanding of simple engineering and technology related practices [0.10] | LBEO3.1: | Labourers carry out labour works with the proper understanding of simple structural and architectural concepts [0.3] |

| LBEO3.2: | Labourers assist with the tasks related to flow measurements, soil testing and surveying procedures [0.4] | |

| LBEO3.3: | Labourers use electrical sources following safety regulations [0.3] | |

| LBEX4: Improving the performance of labourers on understanding and application of technologies used and methods followed in construction works [0.18] | LBEO4.1: | Labourers follow health and safety guidelines in all types of labour works at the construction site [0.3] |

| LBEO4.2: | Labourers carry out labour operations with the proper cognitive and manual skills in technologies used [0.5] | |

| LBEO4.3: | Labourers handle the equipment properly in machinery operations [0.2] | |

| LBEX5: Improving the material handling abilities of labourers [0.24] | LBEO5.1: | Labourers use construction materials in labour work with a basic understanding of the properties and behaviour of materials [0.4] |

| LBEO5.2: | Labourers handle tools to properly follow the procedures in material testing activities [0.6] | |

| LBEX6: Improving the performance of labourers on applying green practices in construction [0.10] | LBEO6.1: | Labourers follow the green practices in labour works (eg. water supply, waste disposal, material usage, etc.) with the understanding of the importance of environmental sustainability [0.6] |

| LBEO6.2: | Labourers explain the importance of the application of energy conservation methods and other green practices to co-workers [0.4] | |

| LBEX7: Improving the management related skills/abilities of labourers required in construction works [0.06] | LBEO7.1: | Labourers follow the guidelines/procedures related to quality assurance and control practices in labour operations [0.6] |

| LBEO7.2: | Labourers manage themselves to strengthen their financial background for personal life aspects [0.3] | |

| LBEO7.3: | Labourers follow the aspects of labour laws for career benefits [0.1] | |

Methodology

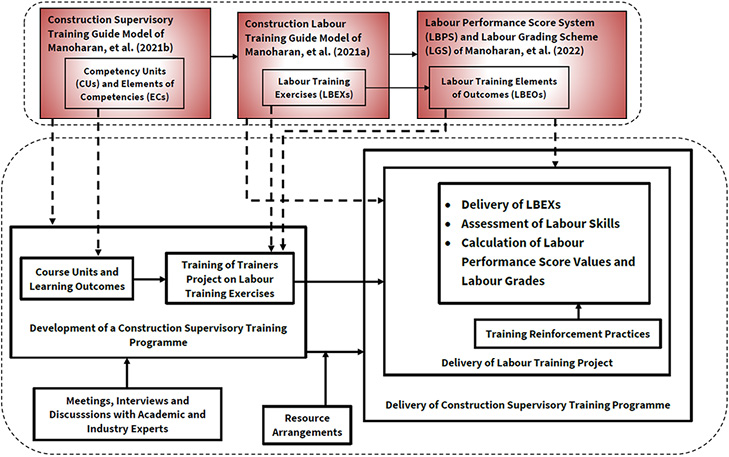

A comprehensive methodology was adopted for this study, as shown in Figure 1. The problem-focused and action-oriented communication approaches were used throughout the study processes with the consideration of emerging challenges and opportunities of the industry in new normal situations. Those approaches are very useful for understanding the issues, exchanging information, generating ideas and finding solutions in a process (Manoharan, et al., 2021a). Importantly, the generalised training guide models and systems highlighted in the literature review of this study were used as the basis for the development of the study methodology. The significance of the applications of these models and systems was verified by the experts’ reviews and discussions. This will be the first study that applied those models and systems in the industry practices by focusing on relevant units of analysis.

Development of a New Construction Supervisory Training Programme

Based on the construction supervisory training guide model of Manoharan, et al. (2021b), a new construction supervisory training programme was systematically designed through the following steps to achieve the diploma level of the National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) Framework of Sri Lanka. These diploma holders will be capable of applying good practices on labour skills to improve the performance and productivity of labour in construction projects. A series of meetings, interviews and discussions were held throughout the following processes with the involvement of academic and industry experts, including institutional directors, construction managers, engineers and technical officers.

• The structure of the training programme was designed based on the competency units proposed in the Manoharan, et al. (2021b) model. Each competency unit was named with a course unit. The aim of each course unit was developed based on the respective competency unit.

• The total number of credits of the training programme was decided according to the requirements of the qualification level to be achieved. The total credits were then distributed among the course units based on the industry requirements through experts’ interviews and discussions.

• Learning outcomes were then developed for each course unit based on the elements of competencies presented in the Manoharan, et al. (2021b) model.

• The detailed contents were developed for each course unit based on the elements of competencies and the mapping results presented in the Manoharan, et al. (2021b) model. The learning contents, teaching and learning activities, hourly breakdown and resource arrangements were designed accordingly. Assessment methods were designed based on the distributed weights of the elements of competencies presented in the model.

• Industry consultative workshops were conducted with the participation of more than 25 experts to revise the curriculum of the developed training programme. The detailed contents of each course unit were revised based on the comments and suggestions received from those experts.

• The developed training programme was reviewed by a panel consisting of six experts who had superabundant academic and industry experience in the construction field and training development.

Considering the need for the systematic training delivery with a long-term focus, the experts’ discussions further focused on the processes unbiasedly, which were the selection of the training institution through SWOT analysis, development of by-laws, obtaining necessary approvals on the training curriculum and by-laws, formation of the Board of Study and the arrangements of monetary, human and other resources. On the other hand, course promotion activities mainly focused to increase the awareness of the industry sector towards fulfilling the need of upgrading the current practices with the direct scope of improving the performance of construction operations. By following the required components of by-laws, a total of 70 construction supervisors were selected for the course registration based on their qualifications and performance in the selection interviews. Considering the selected candidates (construction supervisory workers), the majority of them were working on building (40%) and road/highway (38.6%) construction projects, while a notable portion of them (17.1%) was working on water supply projects. Notably, all of them had more than one year of work experience in the construction field, where the majority (30%) were in the range of 6 – 10 years.

Delivery of Labour Training Project

The most significant component of the developed construction supervisory training programme is the inclusion of the course unit ‘Training of Trainers Project on Labour Training Exercises,’ which was designed based on the construction labour training guide model presented by Manoharan, et al. (2021a). In this course unit, the elements of competencies required for construction supervisory workers to provide necessary training to labourers working at construction sites were designed based on the construction supervisory guide model of Manoharan, et al. (2021b).

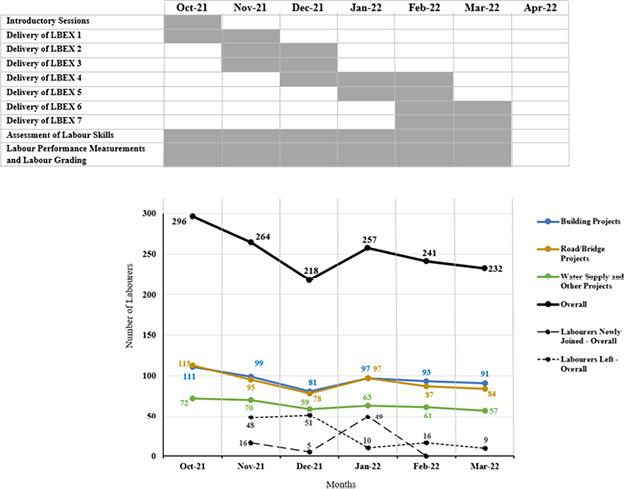

According to the planned steps, methods and procedures listed in the developed course unit ‘Training of Trainers Project on Labour Training Exercises,’ the labour training exercises were systematically delivered by the construction supervisory workers at their respective projects (23) for six months (October 2021 – March 2022) with the focus on labour performance measurements and labour grading as the major units of analysis, as shown in Figure 2.

Based on the LBEXs and LBEOs shown in Table 1, the learning materials were developed in a number of short handbooks, which included the relevant basic theories, instructions, methods, procedures and applications with simple explanations to achieve each LBEO. These handbooks were written in the mother language of labourers (Sinhala and Tamil) and reviewed by a panel of academic and industry experts. The handbook materials were shared among labourers to promote their self-learning abilities. The necessary demonstrations, guidelines and on-site training activities were continuously delivered for the labourers based on the developed learning materials. A number of video clips were also created and shared with the labourers to provide the necessary explanations of the learning contents included in each short handbook. In order to improve the awareness of some important topics among labourers, notices/posters were designed, including necessary figures, tables and flow diagrams for displaying at the necessary worksites locations. Furthermore, the necessary brainstorming sessions were conducted to make labourers perform independently for their lifelong learning to the next normal situations.

Assessment of Labour Skills

Based on the recommendation of Manoharan, et al. (2022), the assessment sheets were designed to assess the competencies of labourers considering the level of descriptors under the categories of process, learning demand and responsibilities mentioned in the NVQ Framework of Sri Lanka (See Table 2). The construction supervisors were trained to be familiar with these levels of descriptors to indicate the level of each category under each LBEO for a labourer based on the continuous observations on his/her work involvement, oral questions, short written tests and other suitable activities at construction sites. The assessment of labour skills was continuously and performed in parallel with the delivery of labour training components (as described in Figure 2).

| Level | Process (P) | Learning Demand (L) | Responsibilities (R) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carry out process that (P1): - are limited in range - are repetitive and familiar - are employed within closely defined contexts - are single processes | Employing (L1): recall - a narrow range of knowledge and cognitive skills - no development of new ideas | Applied (R1): - in directed activity - under close supervision - with no responsibility for the work or learning of others |

| 2 | Carry out process that (P2): - are moderate in range - are established and familiar - offer a clear choice of routine responses - involve some prioritising of tasks from known solutions | Employing (L2): - basic operational knowledge and skill - readily available information - known solutions to familiar problems - little generation of new ideas | Applied (R2): - in directed activity with some autonomy - under general supervision and quality control - with some responsibility for quantity and quality - with possible responsibility for guiding others |

| 3 | Carry out process that (P3): - require a range of well-developed skills - offer a significant choice of procedures requiring prioritisation - are employed within a range of familiar contexts | Employing (L3): - some relevant theoretical knowledge - interpretation of available information - discretion and judgement - a range of known responses to familiar problems | Applied (R3): - in directed activity with some autonomy - under general supervision and quality checking - with significant responsibility for the quantity and quality of output - with possible responsibility for the output of others |

| 4 | Carry out process that (P4): - require a wide range of technical or scholastic skills - offer a considerable choice of procedures requiring prioritisation to achieve optimum outcomes - are employed in a variety of familiar and unfamiliar contexts | Employing (L4): - a broad knowledge base incorporating some theoretical concepts - analytical interpretation of information - informed judgment - a range of innovative responses to concrete but often unfamiliar problems | Applied (R4): - in self-directed activity - under broad guidance and evaluation - with complete responsibility for quantity and quality of output - with possible responsibility for the quantity and quality of the output of others |

Calculation of Labour Performance Score Values (Lbps) And Labour Grades

As per the guidelines mentioned by Manoharan, et al. (2022), the following steps were taken for the calculation of LBPS values and labour grades.

• Through the process of labour skill assessments (mentioned above), the level descriptor was determined by construction supervisors for each LBEO under each category (process [P], learning demand [L] and responsibilities [R]) based on the NVQ framework of Sri Lanka (TVEC, 2009). The following scores were assigned for each level of descriptor under each category.

◦ Process (P) - P1: 25; P2: 50; P3: 75; P4: 100

◦ Learning Demand (L) - L1: 25; L2: 50; L3: 75; L4: 100

◦ Responsibilities (R) - R1: 25; R2: 50; R3: 75; R4: 100

Equal weights were assumed for each category (P, L and R), and the average score was then calculated for each labourer under each LBEO based on the scores mentioned above.

• The performance score of each labourer under each LBEX was calculated using the following formulas.

LBEX1 = 0.4 * LBEO1.1 + 0.6 * LBEO1.2

LBEX2 = 0.6 * LBEO2.1 + 0.3 * LBEO2.2 + 0.1 * LBEO2.3

LBEX3 = 0.3 * LBEO3.1 + 0.4 * LBEO3.2 + 0.3 * LBEO3.3

LBEX4 = 0.3 * LBEO4.1 + 0.5 * LBEO4.2 + 0.2 * LBEO4.3

LBEX5 = 0.4 * LBEO5.1 + 0.6 * LBEO5.2

LBEX6 = 0.6 * LBEO6.1 + 0.4 * LBEO6.2

LBEX7 = 0.6 * LBEO7.1 + 0.3 * LBEO7.2 + 0.1 * LBEO7.3

• The LBPS value was then calculated for each labourer using the following formula.

LBPS = 0.23 * LBEX1 + 0.10 * LBEX2 + 0.10 * LBEX3 + 0.18 * LBEX4

+ 0.24 * LBEX5 + 0.10 * LBEX6 + 0.06 * LBEX7

• The following criteria were used to grade labourers based on their LBPS values.

LBPS value range: 75–100; Grade: A; Colour code: Green

LBPS value range: 50–74; Grade: B; Colour code: Yellow

LBPS value range: 25–49; Grade: C; Colour code: Orange

LBPS value range: 0–24; Grade: D; Colour code: Red

Training Reinforcement Practices

In order to assess whether the training was undertaken as per the desired direction, a checklist was prepared to regularly focus on the fulfilment of the training objectives, supervisors’ performance, training contents, selection of training methods, support getting from the organisational management and follow-up actions throughout the labour training delivery at the selected sites.

Results and Discussions

Overall, the assessment of previous practices and needs in the selected 23 projects showed various problematic areas related to labour performance and highlighted the importance of the application of the labour training elements for those projects. Interviews with labourers working on those projects unveiled that the majority of them did not complete their school education. In some construction sites, though the labourers were categorised as skilled or unskilled labourers, no systematic mechanisms were found for this categorisation. Though the overall work experience varied in a range of 0 – 40 years among the labourers, the majority of them did not have proper NVQ qualifications/certifications. It was spotlighted that the labourers had not been provided with adequate training facilities by the organisations. No systematic mechanisms/practices were found for performance evaluations on labour operations in those selected projects. Figure 2 illustrates the participation of labourers in the labour training exercises for each month in the selected projects.

Figure 2. Labour training delivery schedule and participation of labourers in the labour training exercises

Overall, a total of 296 labourers followed the labour training in the selected projects during the first month, and this dramatically reduced to 218 until the third month. A notable number of labourers left worksites during the period due to various reasons, as mentioned below.

• The majority of the labourers were working with casual appointments at the selected worksites.

• Due to material shortages and the sudden increase in material prices in the country, some projects experienced temporary shutdowns for some days/weeks. Some projects experienced very slow progress in the planned activities. Hence, a notable number of labourers left their workplaces temporarily or permanently.

• Bad weather conditions also forced some firms to stop some project activities for a period.

• Some labourers took long seasonal holidays from their worksites.

• Covid 19 pandemic issues

However, the overall number of labourers suddenly increased to 257 during the fourth month due to the absence/reduction of the above-mentioned impacts. Considering the difficulties in the smooth completion of the planned training tasks, it was decided not to take new labourers into the labour training circle in each project during the fifth and sixth months. The overall number of labourers further reduced slightly during the last two months, and the training exercises ended up with 232 labourers (buildings – 91; roads/highway – 84; Water supply and others – 57) overall at the end of the sixth month.

Based on the training reinforcement practices (discussed in the methodology section), the direction of the training delivery was continuously assessed and revealed the following results in all the selected projects.

• The labour training activities progressed throughout the planned duration as per the training objectives and planned procedures.

• The vast majority of the construction supervisors performed at a satisfactory level in the labour training tasks.

• The contents of the training were satisfactorily covered for all the LBEXs.

• The training components were delivered according to the planned methods and practices.

• The organisational management and the CMTs provided proper support for the delivery of the labour training components.

• The majority of labourers provided their training involvement at a satisfactory level.

• The necessary measures were taken against the identified challenges in some projects to conduct the training tasks in the right direction.

Labour Performance Scores and Grading

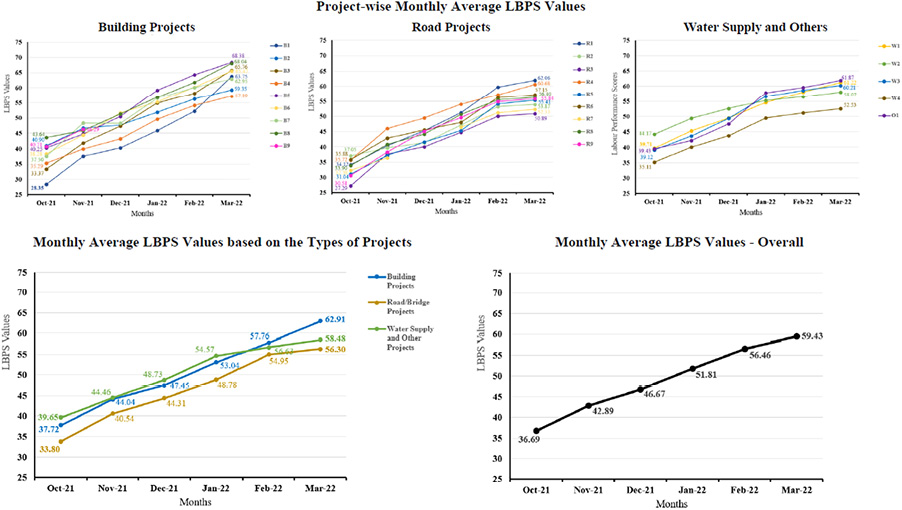

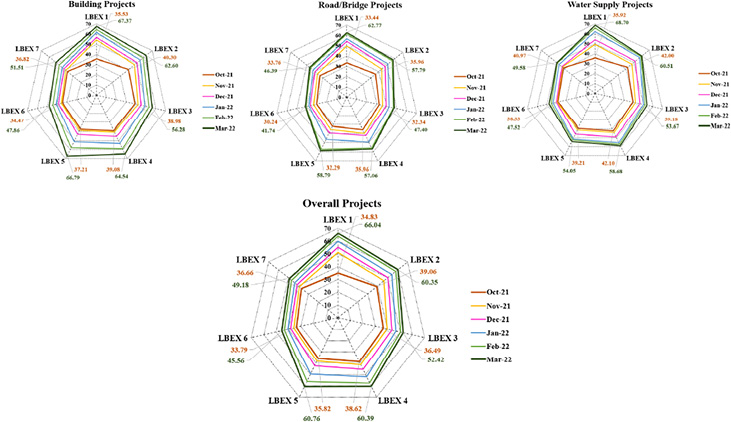

The monthly LBPS values were obtained in the selected projects, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Figure 3 displays how much labour performance scores varied for each LBEX between the months, where Figure 4 illustrates the variations in monthly average LBPS values based on the project categories. Overall, the results confirm that the labour performance had improved up to certain levels for all the LBEXs in all project categories. Compared to the starting point, the overall labour performance increased by almost 60% within six months of the training period, as per the overall quantitative results discussed below. Considerable levels of performance increase were reported in the soft skills (90%) and material handling skills (70%) of labourers, whereas moderate levels of performance rise were noted in the labour competency elements associated with the application of simple engineering/technology-related practices (44%), construction methods and technology (56%), green practices (36%) and fundamental management aspects (34%).

Figure 3. Variations in monthly labour performance scores among LBEXs

Figure 4. Variations in monthly average LBPS values

The study reports a dramatic improvement in labourers’ soft skills in all project types between the first two months since the labour training projects mainly focused on LBEX 1 (Improving the soft skills of labourers required in the construction works). The soft skills of labourers further gradually improved over the following four months of the training period. Overall, the average performance score of LBEX 1 increased from 34.83 to 66.04 during the labour training delivery. In particular, the results show that the labourers’ soft skills were a bit lower in road/bridge projects compared to other types. The experts’ discussions pointed out that the job location, working conditions and construction methods may slightly influence the workers’ soft skills. The overall results ensure the significance of the developed labour training elements for improving work-related transferable and self-management skills of labourers at construction sites.

The labourers’ abilities in applying science and technology related practices (LBEX 2) improved steadily during the labour training period in all project categories. Notably, the performance score values of these abilities were slightly lower among labourers working on road/bridge projects compared to other types. The experts’ discussions revealed that the lesser opportunities for labourers in using ICT applications for work operations of road construction than in other categories may influence this result. Overall, the average labour performance score of LBEX 2 increased from 39.06 to 60.35 during the six months of period. This shows that the developed training elements played a vital role to make labourers work with some relevant theoretical and operational knowledge in measuring and estimating tasks, carrying out tasks with construction drawings, as well as in using ICT tools in work operations.

The labourers’ abilities in understanding simple engineering and technology related practices (LBEX 3) steadily improved during the labour training period in all project categories. Similar to the results of LBEX 2, the performance score values of these abilities were slightly lower among labourers working on road/bridge projects compared to other types. The experts’ discussions pointed out the lesser opportunities for the labourers working in road construction to improve their competencies in understanding simple structural and architectural concepts than the labourers working in other project categories. Overall, the average labour performance score of LBEX 3 increased from 36.49 to 52.42 during the six months of period. This shows that the developed training elements provide a range of well-developed skills in simple engineering and technology related practices among labourers, especially for the understanding of simple structural and architectural concepts, assisting in the tasks related to flow measurements, soil testing and surveying procedures, as well as using electrical sources with safety regulations.

The labourers’ abilities in applying technologies/methods in construction works (LBEX 4) gradually improved during the labour training period in all project categories. Overall, the average labour performance score of LBEX 4 increased from 38.62 to 60.39 during the six months of period. This highlights that the trained labourers are capable of performing processes in directed activities with some autonomy, especially in following health and safety guidelines, handling machinery operations, as well as carrying out other tasks with the proper cognitive and manual skills in the technologies used. According to the LBPS values obtained at the end of the training, compared to the results of the building construction project category, the performance score values of these abilities were slightly lower among labourers working in other project categories. This reveals that the types of machinery operations, construction methods and technologies have an impact on the levels of the work process and learning demand of labourers in construction.

The results describe that the labourers’ material handling abilities (LBEX 5) gradually improved during the first half of the labour training period in all project categories, where the performance score values of LBEX 5 dramatically increased during the second half for the overall category. Especially, a sharp increase in labour performance scores of LBEX 5 was observed in building projects during this period. Notably, the labour training started to focus on the material handling part in the middle of the period in all the selected projects, and this can be the reason for it. Overall, the average labour performance score of LBEX 5 increased from 35.82 to 60.76 within six months of the training period. According to the LBPS values obtained at the end of the training, there were notable differences in the performance score values of LBEX 5 between the project categories. The reason for these differences is that types of materials, material properties and material testing procedures may influence the material handling abilities of labour in construction.

The results show that the labourers’ abilities in applying green practices in construction operations (LBEX 6) gently improved during the labour training period in all project categories. Overall, the average labour performance score of LBEX 6 increased from 33.79 to 45.86 within six months of the training period. This ensures that the developed labour training programme resulted in the capability of labourers to generate little ideas in green practices of construction operations. According to the LBPS values obtained at the end of the training, the performance score values of LBEX 6 were almost the same for both the building and water supply project categories, where there was a notable gap in the performance score values of LBEX 6 between the road projects and other categories. The experts’ discussions highlighted that the tools and framework are currently available to apply suitable green practices in building and water supply work in the Sri Lankan construction sector, but not good enough when it comes to road construction work.

The study reports that the shape of the variations of LBEX 7 is almost similar to LBEX 6. Overall, the average labour performance score of LBEX 7 gently increased from 36.66 to 49.18 within the training period. This highlights that the trained labourers are capable of performing the processes of directed activities with some autonomy, especially in quality assurance and control practices, financial processes and the aspects related to labour laws and career developments. According to the LBPS values obtained at the end of the training, no significant differences were obtained in the performance score values of LBEX 7 between different project categories. This ensures that the characteristics of training elements of LBEX 7 are almost common in all types of projects.

The results confirm the significant improvement incurred in the performance of labour for all LBEX categories in all types of projects, as shown in Figure 3. At the beginning of the training, the majority of the labourers had a narrow range of knowledge and skills to carry out their tasks in all LBEX categories. According to the LBPS values obtained at the end of the training, the majority of the trained labourers have become as capable of carrying out the tasks related to LBEX 3, LBEX 6 and LBEX 7 with operational knowledge and skills. In view of the other four LBEX categories, the majority have grown to perform the work process with some relevant theoretical and operational knowledge and skills.

According to Figure 4, at the beginning of the labour training exercises, monthly average LBPS values were 37.72, 33.80 and 39.65 in building, road/bridge and water supply/other project categories, respectively. At the end of the training, it has risen to 62.91, 56.30 and 58.48 among those types of projects, respectively. Considering the overall category, the monthly average LBPS values steadily increased from 36.69 to 59.43 within the six months of period. The results indicate similar patterns in the variations of LBPS values between the different types of projects with small marginal differences. This affirms the generalisability of the developed work-based training components among a wide range of construction projects. The overall results spotlight the significant behavioural changes incurred in labour operations by improving labour performance. When the labour training began, the majority of the labourers could carry out their work processes within a limited range and repetitive within closely defined contexts. They had a narrow range of knowledge and skills without having the ability to generate new ideas. They were able to carry out their processes under close supervision without having any kinds of responsibilities for the work outputs. At the end of the labour training, the majority of the trained labourers were capable of carrying out their work processes that are moderate in range within familiar contexts. They demonstrated a wide range of basic operational knowledge and skills as well as some theoretical knowledge with the ability to generate some new ideas. They were capable of carrying out the work processes under general supervision with some autonomy and little responsibility for quantity and quality. They have also grown to guide inexperienced workers at worksites.

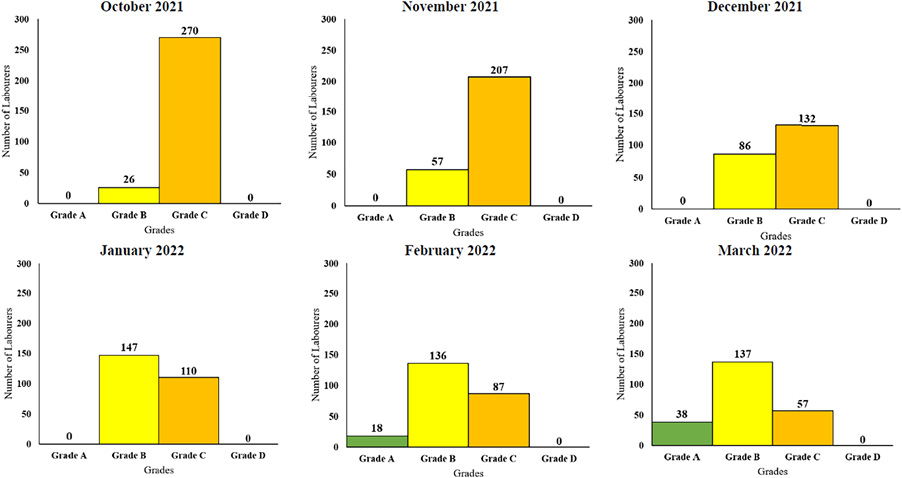

The monthly variations in the labour grades are reported, as shown in Figure 5. Overall, a total of 26 labourers were in grade B and 270 labourers in grade C, whereas no labourers were in grade A and grade D at the end of the first month. Though there were fluctuations in the total number of labourers who followed the labour training each month, the number of labourers in grade B increased to 147 until the end of the fourth month. It started to reduce during the last two months because the number of labourers upgrading their grades from B to A was higher than the number of labourers upgrading from grade C to grade B. When it comes to the number of labourers in grade C, a sharp decline was reported until the end of the third month, and it gently decreased during the last three months. At the end of the sixth month, a total of 38 labourers were in grade A, 137 labourers were in grade B, and 57 labourers were in grade C. Notably, no labourers were in grade D in all the categories in all months. The approximate ratio value between the grade A, grade B and grade C labourers was 1:2.5:1 in building projects, 1:5:2.5 in road/bridge projects and 1:4:1 in water supply and other projects at the end of the sixth month.

Figure 5. Variations in labour grades between the months

Conclusion

The study has presented the methodical practices to achieve higher performance levels of labour operations at construction sites through systematic work-based training components. It describes the patterns of the overall changes in labour performance considering different categories of competency elements and types of construction works/projects. It provides efficacious mechanisms to display the cross-section of labourers working on a construction project to enable identifying their individual strengths and weaknesses within a wide range of competency elements and outcomes. It lays out a functional roadmap for classifying labourers into different grades based on their performance levels, which furnishes standardised ways for the application of resource levelling and utilisation practices in site management and planning.

The study accentuates that the shape of labour performance can be viewed by the combination of the range of work processes, learning demands and responsibilities. This concept provides the standard base for reinforcing supervisors’ observation skills on labour work outputs towards methodically carrying out the performance evaluations. As a result, the construction supervisory workers will be able to deliver the work-based labour training exercises at their worksites, as well as perform labour skill assessments and labour performance measurements in a systematic manner. This may lead to an increase in the number of certified NVQ assessors in the country. The study outcomes add new characteristics to the role of supervision practices for achieving higher performance and productivity of labour outputs. Accordingly, the study opens a new window to strengthening the values of construction supervisors in the construction sector.

The study emphasises that the labourers’ theoretical knowledge, operational skills and abilities in generating ideas are the key elements to deciding the characteristics of supervision practices needed. The findings affirm that the labour training components applied in this study have made a significant influence in transforming the working patterns of labourers to the new normal situations. The majority of the trained labourers are able to carry out their job tasks with well-improved transferrable and self-management skills. They have become familiar with the necessary application of fundamental practices related to science, technology and engineering in their work operations. The proposed work-based training practices have played a functional role in making labourers capable of performing processes in directed activities with some autonomy and a little responsibility, especially in taking measurements and estimations, following health and safety guidelines, handling materials and machinery operations, as well as carrying out other tasks with the proper cognitive and manual skills in technologies used. The study outcomes further reinforce the capability of labourers to generate some ideas in green practices of construction operations as well as to adapt them to follow the procedures of quality assurance and control practices. Importantly, the study has laid the platform for improving the job standards of labourers as well as encouraging them to adapt themselves to lifelong learning practices for successfully facing the challenges and opportunities related to their careers. Hence, authors and publishers may pay attention to this, and a significant rise is expected in the books published for construction labourers and school leavers (who begin careers in the construction field after their school education).

The overall research findings provide a link between institutional and industrial policies and practices, supporting the enhancement of the sector’s total quality of labour capacity, including professional, technical and vocational competence. The research findings are anticipated to have a substantial impact on the industrial processes in other developing countries, despite the fact that the study’s applications and scope are restricted to the Sri Lankan context. This research also suggests that future studies focus on developing new apprenticeship tools, analysing apprenticeship outcomes and assessing the characteristics of various professions or industrial sectors in diverse contexts. The research also suggests that future studies examine the use of digital technology in the labour training components to strengthen the apprenticeship delivery methods and move them toward next normal characteristics. This study also provides a fresh perspective on developing new tools that employ digital technology, broadening the suggested methods for attracting industrial firms from around the world and strengthening the generalisation of the activities.

References

Dickinson, J.K., Woodard, P., Canas, R., Ahamed, S. and Lockston, D., 2011. Game-based trench safety education: development and lessons learned. Journal of Information Technology in Construction, 16, pp.118–32.

Dinh, T.H. and Nguyen, V.T. 2019. Analysis of affected factors on construction productivity in Vietnam. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 10(2), pp.854–64.

Fernando, P.G.D., Fernando, N.G. and Gunarathna, M.A.C.L., 2016. Skills developments of labourers to achieve the successful project delivery in the Sri Lankan construction industry. Civil and Environmental Research, 8(5), pp.86–99.

Gao, Y., Gonzalez, V.A. and Yiu, T.W., 2019. The effectiveness of traditional tools and computer-aided technologies for health and safety training in the construction sector: a systematic review. Computers and Education, [e-journal] 138, pp.101–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.05.003

Ghate, P.R. and Minde, P.R., 2016. Labour productivity in construction. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307138481_labour_productivity_in_construction/download. [Accessed 14 October 2020].

Manoharan, K., Dissanayake, P., Pathirana, C., Deegahawature, D. and Silva, R., 2020. Assessment of critical factors influencing the performance of labour in Sri Lankan construction industry. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] pp.1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1854042

Manoharan, K., Dissanayake, P., Pathirana, C., Deegahawature, D. and Silva, R., 2021a. A competency-based training guide model for labourers in construction. International Journal of Construction Management, [e-journal] pp.1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2021.1969622

Manoharan, K., Dissanayake, P., Pathirana, C., Deegahawature, D. and Silva, R., 2021b. A curriculum guide model to the next normal in developing construction supervisory training programmes. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, [e-journal] pp.1–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-02-2021-0038

Manoharan, K., Dissanayake, P., Pathirana, C., Deegahawature, D. and Silva, R., 2022. A labour performance score and grading system to the next normal practices in construction. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, [e-journal] pp.1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-10-2021-0125

Mistri, A., Patel, C.G. and Pitroda, J.R., 2019. Analysis of causes, effects and impacts of skills shortage for sustainable construction through analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Technical Innovation in Modern Engineering & Science, 5(5), pp.168–76.

Mojahed, S. and Aghazadeh, F., 2008. Major factors influencing productivity of water and wastewater treatment plant construction: Evidence from the deep south USA. International journal of project management, 26(2), pp.195-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.06.003

Murari, S.S. and Joshi, A.M., 2019. Factors affecting labour productivity in precast construction industry. Proceedings of Fourth National Conference on Road and Infrastructure, RASTA - Center for Road Technology, Bangalore, India, 4-5 April 2019. pp.163–69.

Ojha, A., Seagers, J., Shayesteh, S., Habibnezhad, M. and Jebelli, H., 2020. Construction safety training methods and their evaluation approaches: a systematic literature review. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Construction Engineering and Project Management, Hong Kong, 7-8 December 2020. pp.188–97.

Onyekachi, V.N., 2018. Impact of low labour characteristics on construction sites productivity in EBONYI state. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, 5(10), pp.7072–87.

Pham, H.C., Dao, N.N., Pedro, A., Le, Q.T., Hussain, R., Cho, S. and Park, C.S., 2018. Virtual field trip for mobile construction safety education using 360-degree panoramic virtual reality. International Journal of Engineering Education, 34(4), pp.1174–91.

Sangole, A. and Ranit, A., 2015. Identifying factors affecting construction labour productivity in Amravati. International Journal of Science and Research, 4(5), pp.1585–88.

Shoar, S. and Banaitis, A., 2019. Application of fuzzy fault tree analysis to identify factors influencing construction labor productivity: a high-rise building case study. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, [e-journal] 25(1), pp.41–52. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2019.7785

Silva, G.A.S.K., Warnakulasuriya, B.N.F. and Arachchige, B.J.H., 2018. A review of the skill shortage challenge in construction industry in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research, 2(1), pp.75–89.

Siregar, S., 2017. A study of work-based learning for construction building workers. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, [e-journal] 970, pp.1–6. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/970/1/012024

TVEC (Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission of Sri Lanka), 2009. National Vocational Qualification Framework of Sri Lanka Operations Manual. Colombo, Sri Lanka: TVEC.

TVEC (Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission of Sri Lanka), 2017. Construction Industry Sector Training Plan 2018 – 2020. Colombo, Sri Lanka: TVEC.