Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 25, No. 1

March 2025

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Suitability of Basalt Textile-Reinforced Granite–Periwinkle Shell Concrete for Sustainable Construction in Nigeria

Paschal Chimeremeze Chiadighikaobi1,*, Blossom Chinazor Ubani-Wokoma2

1 Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria, chiadighikaobi.paschalc@abuad.edu.ng

2 Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria, blossomuw@gmail.com

Corresponding author: Paschal Chimeremeze Chiadighikaobi, Department of Civil Engineering, Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria, chiadighikaobi.paschalc@abuad.edu.ng

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i1.8757

Article History: Received 05/08/2023; Revised 25/09/2024; Accepted 05/10/2024; Published 31/03/2025

Citation: Chiadighikaobi, P. C., Ubani-Wokoma, B. C. 2025. Suitability of Basalt Textile-Reinforced Granite–Periwinkle Shell Concrete for Sustainable Construction in Nigeria. Construction Economics and Building, 25:1, 171–202. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v25i1.8757

Abstract

Multiple construction methods have been researched and implemented to reduce the harmful effects of construction on society such as using alternative strengthening materials and aggregates in concrete. This study investigates the suitability of granite (G)–periwinkle shell (PS) as coarse aggregate in concrete for construction. The objectives of this study are to determine the mechanical properties of G–PS concrete confined and not confined in basalt textile (BT), the possibility of achieving lightweight concrete, the durability of the G–PS concrete, and the impact of BT and PS on the construction economy. Slump, density, compressive strength, split tensile, modulus of elasticity, and water absorption tests were conducted on 108 concrete cubes and 180 concrete cylinders and analyzed to determine the behavior of the concrete. From the experiments, the workability of the concrete mix, density, and mechanical properties of the concrete reduced with a decrease in the percentages of granite and an increase in the percentages of PSs. The concrete with 100%G and 0%PS had the highest slump value of 7 cm while the concrete with 0%G and 100%PS recorded the lowest slump value of 2.5 cm. Confining BT on the concrete cylinders improved their mechanical properties. Although concrete with 100%G and 0%PS proved to have the best strength, this study concludes that PS concrete is suitable for light constructions and load-bearing structural members as the strength of concrete having some percentages of PS proved to be good and even better when confined in BT. It was also observed in a discussion that this concrete type is economical and easy to manage in construction. It is recommended that this type of concrete be implemented in the construction of structural members because the properties of this concrete are suitable for the Nigerian environment, and incorporating PSs in construction is a sustainable means and a way to facilitate the actualization of the sustainable development goal of “Sustainable Cities and Communities and Responsible Production and Consumption”.

Keywords

Lightweight Concrete; Periwinkle Shell Concrete; Basalt Textile Confined Concrete; Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11); Responsible Production and Consumption (SDG 12)

Introduction

The building sector is expected to utilize more resources and energy in the future due to megatrends such as the growing global population, urbanization, and quantity of occupied living space per inhabitant (World Economic Forum, 2016). If the rate of building construction continues at such a high speed, global raw material extraction might increase by more than double by the year 2050 (Sameer and Bringezu, 2019).

According to Manjunatha, et al. (2021), it is impossible to overstate the significance of concrete in almost every aspect of civil engineering practice and other various building projects. Concrete is extensively and massively employed practically anywhere infrastructure is needed by humans. Concrete is used more often than all other building materials combined, including wood, steel, glass, plastics, aluminum, and iron. Although concrete is a practical and widely used construction material, the need to develop concrete with low-carbon materials and materials that involve less carbon dioxide emission during production is necessary to achieve sustainable construction.

The construction sector is a vital component of the global economy as it makes up 13% of the world’s gross domestic product and 7.6% of all employed people worldwide [Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development (ICED), n.d.; Scheurer, et al., 2023]. Concurrently, the construction industry accounts for over 40% of the world’s raw material consumption, roughly 33% of the world’s energy consumption, and roughly 40% of the world’s solid waste production (Choi, 2019; Backes and Traverso, 2021). As a result, the building industry will need to be included in any endeavor to decrease greenhouse gas emissions globally (Scheurer, et al., 2023).

These statistics and numbers illustrate the significance of a paradigm shift in the building sector. Inevitably, there will be more development due to the growing global population; therefore, environmental issues must be resolved quickly and thoroughly. Authorities in several nations are preparing to implement regulations, or have already done so, to restrict the use of resources and energy in the building sector (Pasanen, et al., 2021).

Sustainable construction is the implementation of a healthy environment rooted in ecological principles. Sustainable construction focuses on six principles: conserve, reuse, recycle, renew, protect nature, and create nontoxic and high-quality materials (Akadiri, Chinyio and Olomolaiye, 2022). Sustainable development uses locally available, energy-efficient, and sustainable building materials. This allows occupants to live in a healthy and comfortable environment throughout the life cycle of the building. The life cycle comprises material production, planning, design, construction, operation, and maintenance processes (Patil and Patil, 2017).

Typical negative impacts of construction activities include waste production, mud, dust, soil, and water contamination and damage to public drainage systems, destruction of plants, visual impact, noise, traffic, increased parking space shortage, and damage to public space (Kaja and Goyal, 2023). The Federal Government of Nigeria has pressed on the issue of sustainable construction and encouraged stakeholders to adopt sustainable development methods in the country (Oke, et al., 2023). The clamor by stakeholders for sustainable development in Nigeria is only relatively recent. Before 1989, policies governing the environment were fragmented into different government agencies’ documents (Ogunkan, 2022). This policy was revised once and environmental regulations are only being formulated recently (Nwachukwu, 2024). The Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) reiterated that stakeholders must make constant efforts for sustainable development to be adopted in the nation (Isang, 2023). These needs gave rise to sustainability becoming an increasingly important topic for construction research in Nigeria. In many ways, sustainability in Nigeria has reached an unprecedented peak. Unheard of decades ago, much research has been conducted to create awareness and facilitate the implementation of sustainable construction in Nigeria. Various building techniques, such as the use of substitute strengthening materials and aggregates in concrete, have been studied and put into practice to lessen the negative impacts of construction on society and solve the issues brought about by the absence of sustainable construction (Althoey, et al., 2023; Nilimaa, 2023; Rivera-Lutap, et al., 2024). One way to lessen the impact of the construction sector is to employ novel materials that need less energy, and materials that emit fewer greenhouse gases.

Many researchers have focused on the usefulness of periwinkle shells (PSs) as an alternative material for concrete aggregates. The suitability of PS as a replacement for gravel in concrete production has been investigated by Agbede and Manasseh (2009). In their research, coarse aggregate was replaced at 1:0, 1:1, 1:3, 3:1, and 0:1 PS to G by weight. Concrete cubes with 100% PS were lighter and had lower compressive strength than those containing G. The 28-day density and compressive strength of PS were 1,944 kg/m3 and 13.05 N/mm2, respectively.

Sustainable construction and materials

Sustainable construction is regarded as the future of structural design. It follows the fundamental principle that says the depletion of energy and resources due to the construction and operation of a structure must be minimized (Mavi, et al., 2021). This principle concerning concrete can be implemented by using materials in the most efficient way possible with consideration of their strength and durability (Akadiri, Chinyio and Olomolaiye, 2022). This can be done using lightweight concrete (LWC), which is regarded as sustainable concrete and by using alternative strengthening materials. A popular method of producing LWC is by replacing the normal aggregates with waste materials (Ting, et al., 2019). Incorporating waste materials into concrete provides a solution for the management and diversion of waste products while minimizing the use of normal aggregates, which are obtained in a harmful manner, or minimizing the depletion of natural resources (Tavakoli, Hashempour and Heidari, 2018). Past research has determined that materials such as PSs (Omisande and Onugba, 2020), palm kernel shells (Oyejobi, et al., 2020; Ifeanyi, Chima and Chukwudubem, 2023), and bamboo chippings (Park, et al., 2019) can be used to develop concrete with properties that make it suitable for use in construction.

Periwinkle shell concrete

Periwinkle shells (PSs) have gained the interest of many researchers as an alternative coarse aggregate in concrete. For more than two decades, there have been multiple research papers done to determine the suitability of PS as a coarse aggregate in concrete (Agbede and Manasseh, 2009; Omisande and Onugba, 2020). It was determined that PSs can be used to produce structural LWC. The study by Olugbenga (2016) gave an analysis of the possibility of producing LWC with PSs. From this research, it was concluded that a 20%–30% replacement of coarse aggregates with PSs would result in LWC. Also, the study by Osarenmwinda and Awaro (2009) researched the potential of PS concrete concerning compressive strength (fc). From the result of their experiment, it was concluded that the strength values determined met the ASTM C330/C330M17A recommended minimum strength for structural LWC. The study by Umasabor (2019) analyzed the mechanical properties of PS concrete and its advantages. Palm kernel shells (PKS) also received notable attention from researchers on its possibility as a material used for the replacement of coarse aggregates in concrete. Multiple studies have been carried out to determine the mechanical properties of PKS concrete (Emiero and Oyedepo, 2012; Oyedepo, Olanitori and Olukanni, 2015).

LWC is not a recent development in the field of construction. For over 2,000 years, LWC has been used in the construction of various structures. The most popular example of this is the Pantheon in Rome, Italy, which was built in ca. 128 AD (Thienel, Haller and Beuntner, 2020). As time passed and research developed, many varying definitions for LWC concerning density, strength, and type of LWC emerged. Jihad and Ali (2014) simply defined LWC as concrete with a dry density of 300 to 2,000 kg/m³ and a cube fc of 1 to 60 MPa. LWC has a higher strength-to-weight ratio than conventional concrete, better thermal and sound insulation, and less dead load in the structure resulting in fewer structural elements and less steel reinforcement (Mohammed and Hamad, 2014).

LWC has three methods of production: using lightweight aggregates (LWA), inducing bubble voids within concrete, and using only coarse aggregates. The resulting concretes are known as lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC), aerated lightweight concrete (ALWC), and no-fine concrete, respectively (Jihad and Ali, 2014). Examples of LWA used in the production of LWC are shale, clay, shells, and slate. With further research, it was discovered that agro waste has the potential to be used as LWA (Emeghai and Orie, 2021). Due to the availability and accessibility of LWA, periwinkle shells can be sourced without causing harm to the environment.

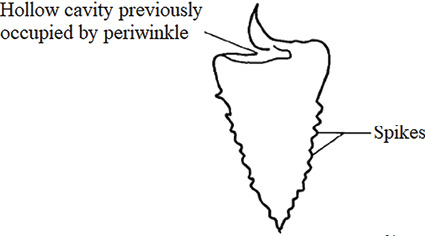

Periwinkle is a small marine snail belonging to the family Littorinidae (class Gastropoda, phylum Mollusca). In Nigeria, they inhabit the riverine and coastal areas of Nigeria, i.e., the Niger Delta area and Lagos Lagoon. PS (Figures 1 and 2) is a waste material obtained after the consumption of the organism known as a periwinkle. The shell is usually greenish blue or dark gray and has a spiral rough appearance (Dahiru, Yusuf and Paul, 2018). The size of a PS ranges from 10 to 30 mm (Elegbede, et al., 2023). PS is usually difficult to dispose and when dumped, the environment becomes polluted. The use of PSs in concrete also solves environmental problems that might arise from dumping PSs (Ugwu and Egwuagu, 2022). A solution to this problem was obtained when it became a viable material for the replacement of coarse aggregates in concrete. For about three decades, a particular state in Nigeria known as Rivers State has made use of periwinkle shell concrete for construction (Agbede and Manasseh, 2009).

Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 2. The appearance of the periwinkle shell.

Source: Osadebe and Ibearugbulem (2009) and Omisande and Onugba (2020).

PS is used as a partial replacement for coarse aggregate in concrete (Tongbram, Singh and Devi 2023). Generally, 70%–80% of the volume of normal concrete is taken up by coarse aggregates, and that value is notably affected by the type of coarse aggregate (Falade, Ikponmwosa and Ojediran, 2010; Sulaiman and Olatunde, 2019). PS weighs significantly less than normal granites. Its bulk density is 60% less than the bulk density of normal granite; thus, its use results in the reduction of the weight and density of the concrete. Therefore, the concrete produced with these PS can be classified as LWC. However, it is to be noted that the production of LWC with PS depends on the quantity of PS used.

The periwinkle shells have been categorized by Osadebe and Ibearugbulem (2009) as lightweight coarse aggregates in compliance with ASTM concrete specifications. Periwinkle shells have also been investigated by Aliyu, Kwami and Sani (2022) as potential coarse aggregates, and it has been found that concrete constructed with them is within the category of lightweight concrete.

The workability of concrete is affected by the addition of PS. From previous research, the workability of the concrete decreases with an increase in the replacement of the normal aggregates with the PSs. The poor workability of the concrete is linked to the structural and textural qualities of the PS. Researchers (Agbede and Manasseh, 2009) noted that rough-textured, angular, and elongated aggregates (Figure 2) require more water in the cement to produce workable concrete than smooth and rounded aggregates. They also noted that it is expected for aggregates’ rough textures and angular form to have good bonding properties with the cement and improve the properties of the concrete. Another factor that affects concrete workability is the hollow parts of the PS. They capture the cement paste and deprive the other constituents of the sufficient materials needed for bonding (Eboibi, Akpokodje and Uguru, 2022).

From previous research, it is concluded that the fc of concrete reduces with an increase in PS content. The study by Sulaiman and Olatunde (2019) explained that as the quantity of PSs increases, the quantity of cement becomes inadequate to form an effective bond with the coarse aggregate. This is attributed to the higher effective surface area of the PSs. Although the strength of concrete is reduced with the addition of PSs, the values obtained in their research range from 17 N/mm2 to 25 N/mm2 and are correlated with the ASTM C330/C330M17A. Omisande and Onugba (2020) determined that with the addition of PSs to concrete, for all curing ages, the split tensile strength reduces and is lower in comparison to normal concrete.

In the study by Aboshio, Shuaibu and Abdulwahab (2018), the researchers partially and fully replaced the concrete coarse aggregate (granite) with PSs by 0%, 30%, 40%, 50%, and 100%. The results showed that the density of the concrete with PS replacement of granite is less than normal (granite) concrete. The concrete fc and splitting tensile strength (fsts) decreased with an increase in the percentages of PS.

The prospect of PS as coarse aggregate in concrete production was investigated by Osarenmwinda and Awaro (2009). The results showed that concretes produced with 1:1:2, 1:2:3, and 1:2:4 concrete mixes provide concrete compressive strengths of 35.67, 19.50, and 19.83 N/mm2 at 28 days, respectively. These strength values met the ASTM C330/C330M17A suggested minimum strength of 17 N/mm2 for structural LWC.

Research on making LWC from PSs and recycled plastic waste was studied by Ede et al. (2021). According to the review, the use of PS is advantageous for satisfactory strengths for normal aggregate concrete and LWC, as well as for good heat resistance and economics, while the use of a lower percentage of waste plastic in concrete results in acceptable strengths for LWC.

The mechanical characteristics of concrete made from palm kernel shells (PKSs) and PSs were compared by Eziefu, Opara, and Anya (2017). The water-to-cement ratio was 0.5, and the concrete mix ratio was 1:2:4. Three sets of concrete mixtures were tested, one with 100% PKSs, one with 100% PSs, and one with 100% granite as the control. At curing days 7, 14, 21, and 28, the concrete cubes were tested for bulk density and fc, respectively. Both the PS concrete and the PKS concrete satisfied the bulk density and fc requirements for LWAC. The results showed that for all curing ages, the PS concrete had a higher fc and a lower bulk density than the PKS concrete. The bulk density and fc of the 28-day PKS concrete were 1,840 kg/m3 and 14.02 N/mm2, respectively; those for the PS concrete were 1,936 kg/m3 and 16.90 N/mm2, and those for granite concrete were 2,496 kg/m3 and 25.95 N/mm2, respectively (Eziefu, Opara and Anya, 2017).

In a recent study, Ogundipe, et al. (2021) suggested that lightweight structural concrete could be made from both PSs and PKSs. In the interim, Dauda, et al. (2018) believed that PS residues could be pozzolanic cement and were useful as a stabilizing agent for improving soil, while Odeyemi, et al. (2020) suggested using sawdust and periwinkle shells to make high-quality particle boards with sufficient strength.

In this study, the workability, density, and fc of periwinkle concrete improved with an increasing percentage of gravel. The reduction in the density of concrete produced with PS can be seen in Table 1, and it justifies the explanation for its usage in coastal states as construction material (Dahiru, Yusuf, and Paul, 2018). Many states in the coastal space of African nations (Niger Delta, Nigeria), for example, have adopted its usage in concrete for over 20 years. Due to its abundance in these areas, its usage has influenced the value of concrete while not compromising the properties of concrete.

| Properties | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Osei and Jackson (2012) | Osadebe and Ibearugbulem (2009) | Yang, et al. (2010) | |

| Size | - | - | 10–20 |

| Specific gravity | 1.73 | - | 1.44–2.65 |

| Density | 619.90 | 694.44 | 517–1,243 |

| Water absorption | 25 | 12.99 | 12.99 |

| Moisture content | - | 8.32 | 8.32 |

| Impact value | 65% | - | - |

| Durability | - | 83 | - |

| Fineness modulus | - | - | 12.99 |

| Uniformity coefficient | - | 1.23 | - |

Source: Omisande and Onugba (2020).

In the findings by Ruslan, et al. (2021), the researchers suggested a high prospect of using PS as coarse aggregate in concrete production. Moreover, several researchers have discovered that the integration of PS was accountable for the decline of the compressive strength of the concrete principally at full granite replacement, and this was presumably a result of weak bonding between PS and the matrix of cement (Osadebe and Ibearugbulem, 2009). The compressive strength of most, 25 MPa, is realizable through the complete substitution of coarse ingredients by PS in concrete.

Concrete’s resistance to elastic deformation is gauged by its elastic modulus. The volume of the component aggregates in the concrete and their elastic modulus has an impact on the E-value of the material. When shells partially replaced cement or aggregates in concrete or mortar, the majority of researchers found that the E-value of the materials decreased (Zhu, et al., 2024). The study by Ahsan, et al. (2022) discovered that adding seashell aggregates to concrete did not significantly lower its elastic modulus. This was primarily because the disintegration of the shells decreased the pore pressure created in the matrix, thereby preserving the elastic modulus.

Periwinkle shell lightweight concrete (PSLWC) is beneficial as a structural material for multiple reasons. It makes use of a locally sourced material that reduces construction costs, promotes infrastructural development, and brings about sustainable structural engineering. It is used in the construction of non-load-bearing walls, nonstructural floors, strip footings, footbridges, lintel-wearing courses, and other light structures.

This study focused on developing lightweight periwinkle concrete that can withstand heavier loads. For this purpose, a low moisture content mix ratio containing basalt textile (BT) as reinforcement was developed and used. The literature search for this study revealed insufficient information regarding the tensile properties of concrete embedded in basalt textiles. Highlighting this knowledge gap, this study exploited it to investigate the effect of basalt textiles on the properties of concrete.

PSLWC like every other concrete is brittle. This brittleness is a major problem in concrete that causes cracks and finally the collapse of structural concrete members. Many researchers have investigated the use of reinforcement materials. These reinforcement materials in different forms and patterns are used in concrete in different ways to achieve different reinforcement methods. One possible novel material combination, which has been researched since the late 1990s, is textile-reinforced concrete. This research study implements the use of basalt textile confined concrete.

Basalt textile confined concrete

Along with the use of waste products, alternative strengthening materials are also considered for the production and reinforcement of concrete. BT, also known as basalt fiber (BF) cloth or basalt woven textile, is a novel material that is currently undergoing research as a suitable material for the reinforcement of concrete. It is a man-made material that is formed from a combination of fine fibers of basalt. Basalt fibers are made from raw basalt rock. Other textiles for the reinforcement of concrete are available such as carbon textiles and alkali-resistant (AR)-glass textiles. Its recyclability, heat resistance, and durability make it an excellent candidate for the development of sustainable infrastructure (Park, Park and Hong, 2020). As BT is still a new innovative material, there is still not enough research on its overall behavior when used as confinement for different types of concrete.

Concrete being a brittle material needs to be strengthened to achieve a durable and sustainable construction material. To improve the strength of concrete, the use of reinforcement is employed, although the strength of concrete can also be enhanced by including some additives in the concrete mix (Ramadan, et al., 2023). The most common ways of improving concrete strength are the use of reinforcing materials like fibers that are used in concrete mix for interior and exterior reinforcement (Mukhopadhyay and Shruti, 2015; Mujalli, et al., 2022), the use of reinforcement bars in the concrete or as jacketing (Chalioris, et al., 2013; Mahmoud, Sallam and Ibrahim, 2022), and the use of mesh and textiles as jacketing or confinement of the concrete (Koutas and Bournas, 2020). All these methods have their function in reducing the brittleness of the concrete. These reinforcement materials are produced from different materials like basalt, glass, plastic, steel, carbon, and asbestos, among others. Research into advanced construction technology with the benefits of sustainability and efficiency has led to the recognition of textile-reinforced concrete (TRC) as a possible alternative to normal concrete. TRC is a form of concrete where the steel bars are removed and the concrete is confined within textile reinforcement (Venigalla, et al., 2022). TRC is regarded as sustainable concrete because of certain qualities. It offers the possibility to use a significantly smaller amount of material in the production of concrete composites. Its use results in structures that have a longer service life than structures constructed with conventional concrete (Alexander and Shashikala, 2020).

Composite materials such as fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) jackets have been successfully used to confine cylindrical prisms and columns under monotonic and cyclic loading. Although limited studies have been conducted to date, all of them reached similar conclusions; confinement was more effective in increasing the compressive strength and ultimate axial strain in concrete (Koutas and Bournas, 2020; Skyrianou, Koutas and Papakonstantinou, 2022). The increase in FRP layers further enhanced both the compressive strength and ultimate axial strain (Raffoul, et al., 2017; Youssf, Hassanli and Mills, 2017). Among all jacketing techniques, the use of FRPs has gained increasing popularity in the civil engineering community due to the favorable properties possessed by these materials, namely, extremely high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, ease and speed of application, and minimal change in the geometry (D’Anna, et al., 2021).

Since this research paper employed basalt textiles to confine the concrete, most discussions would focus on using basalt textiles in concrete. BT (Figure 3) is woven from BF, which is an innovative product derived from a natural resource known as basalt rock. BT is a man-made material that is formed from the interweaving of fine fibers of basalt. The first patent detailing its method of production was developed by a French Scientist named Paul Dhe’ in 1923 and a closed scientific research program on it began in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR) (Kumbhar, 2014). In 1990, the USSR was dismantled so the techniques and research became available to everyone. The two main techniques used to manufacture the basalt textile are the Spinneret technology and Junker’s technology. The Spinneret technique involves uniformly heating the basalt rocks at temperatures between 1,200 and 1,500°C and passing it through platinum-rhodium-heated bushing to form the fine fibers. Junker’s technique, which is primarily used to produce short basalt fibers, is a melt-blowing technique (Chowdhury, Pemberton and Summerscales, 2022). The BT has gained the attention of researchers because of its many beneficial mechanical properties (Liu, et al., 2021). Most research on BT has centered on BT as an additional structural reinforcement for concrete members by determining the mechanical properties of concrete confined in it.

Figure 3. Basalt textile. Source: Authors’ own work.

BT is resistant to fire and thermal insulation because of its mineral composition and many micropores (Pareek and Saha, 2019). The tensile strength of BF varies between 3,000 and 4,840 MPa, which is higher than glass fibers. In comparison to E-glass textiles, basalt textile has higher stiffness and strength (Kumbhar, 2014) and no reactions with air, gases, or water. Its hardness varies from 5 to 9 on Mohr’s scale (Tavadi, et al., 2021). BT has better split tensile strength than the E-glass textile, greater failure strain than the carbon textile, and good resistance to chemical attack, impact load, and fire with less poisonous fumes. From these advantages, the applicability of BT as a structural strengthening material is highly expected (Zhang, et al., 2020; Natarajan, et al., 2024). The study by Kumbhar (2014) compared the mechanical properties of BF to other fibers (Table 2). In a crushed state, the basalt rock has been used for surfacing and filling in roads, tiling in construction, and lining material for pipes carrying high-temperature fluids.

Source: Kumbhar (2014).

Gopinath, et al. (2015) studied the behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with BT. The study gave a comparison of the ultimate load-bearing capacity, ductility, and energy absorption of the BT-strengthened reinforced beams and normal reinforced concrete beams. This study also mentioned the need for more experiments to check the applicability of BT as a strengthening material. Zhang, et al. (2023) studied the axial compressive qualities of concrete columns confined in BT. From previous research, it is observed that concrete strengthened with basalt textile exhibits improved load-bearing capacity. Tests carried out by previous researchers present that there is a 35%–47% increase in the ultimate load-bearing capacity of concrete with the addition of BT. The number of textiles affects these values with the increase in the ultimate bearing capacity being directly proportional to the increase in the number of layers (Zhang, et al., 2023). It also determined that there is an increase in the fsts of concrete strengthened with BT. This research notes that the study of basalt textile reinforced concrete (BTRC) columns is relatively lacking. The study also noted the effect of multiple layers of BT on the mechanical properties of concrete and showed the behavior of concrete strengthened with BT. Multiple factors were considered for determining the mechanical properties of the BTRC beam and basalt textile mortar (BTM) like the number of textile layers and mesh size (Shamseldein, ELgabbas and Elshafie, 2022). These studies captured the possibility of BT as a strengthening material for concrete and areas that need more investigation.

The study by Chiadighikaobi, et al. (2022) analyzed the properties of lightweight concrete reinforced with chopped basalt fiber and confined in basalt fiber polymer. The experimental study compared conventional lightweight concrete to reinforced lightweight concrete. The results demonstrated that expanded clay concrete reinforced with chopped basalt fiber and contained in basalt fiber-reinforced polymer had the best porosity index, fc, and modulus of elasticity (MoE).

The quarrying of stones and rocks to obtain crushed stones and granites has left the environment at risk. This process causes heavy vibration in the soil, which causes serious cracks in the soil and earth structures. In the quest to solve the problems and achieve sustainable construction, this paper implements the use of periwinkle shells as a partial and full replacement for granite. Though periwinkle shell makes concrete structural construction more sustainable, the brittle nature of concrete persists; therefore, this paper implements the use of basalt textiles as confinement to concrete. The use of steel reinforcement materials as a product hurts the environment. The manufacturing process of the steel is harmful to the environment and its inhabitants. The emission of carbon monoxide during steel production is a thing of concern, hence the use of basalt textile, the production of which is not harmful, thereby making it a more sustainable method. The need to achieve lightweight concrete for construction is very important as it reduces the self-weight of the structural member where it is used. The need for upgrading existing structures has been tremendous in the past couple of decades, both in non-seismic areas, due to the deterioration or the introduction of more stringent design requirements, and in seismic areas, where structures designed according to old seismic codes must meet performance levels required by current seismic design standards. One of the most common upgrading techniques for reinforced concrete structures involves the use of jackets, which are aimed at increasing the confinement action in either the potential plastic hinge regions or over the entire member. During the review of previous works related to this experimental research, it was discovered that there is not enough information available on the effects of basalt textiles on the split tensile strength of concrete. Also, no research was found on the confinement or wrapping of periwinkle shell concrete with basalt textiles. Therefore, this research study provides new information assessing the effects of basalt textiles on the split tensile strength of concrete specimens and the effect of basalt textile wrapping on periwinkle shell concrete. This research study aims to investigate the suitability of granite–periwinkle shells as coarse aggregate in concrete for construction. The objectives of this study are as follows:

i. To check the workability of granite–periwinkle shell concrete.

ii. To achieve lightweight concrete.

iii. To investigate the durability of the granite–periwinkle shell concrete.

iv. To determine the mechanical properties of granite–periwinkle shell concrete confined/not confined in basalt textile.

v. To identify the modulus of elasticity of the concrete.

vi. To briefly discuss the economic impact of basalt textile and periwinkle shells on managing construction in Nigeria.

Methods and materials

Experimental materials for this research

To achieve the objectives of this research, some laboratory experiments were conducted. These experiments required the use of materials and aggregates. The materials used in producing the concrete types needed for this research are discussed below.

Cement. The cement used as the binder for the concrete work was Dangote 3X Grade 42.5R Portland cement, and it is conformed to BS EN 197-1:2011 at 700 kg/m3. The 3X stands for Xtra strength, Xtra life, and Xtra yield. The chemical composition of Dangote cement used in this study, compared with the BS limit, is given in Table 3.

| Chemical composition | CaO | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | MgO | K2O | SO3 | Na2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentages | Current study | |||||||

| 61.20 | 18.12 | 2.73 | 4.91 | 1.93 | 0.14 | 1.39 | 0.41 | |

| BS EN 197-1:2011 | ||||||||

| 58.67–63.90 | 17.46–21.59 | 1.21–3.76 | 3.29–6.14 | 0.61–3.30 | ||||

Source: Authors’ own work.

Silica sand as fine aggregates. Silica sand contains a high proportion of silica (normally, but not exclusively, more than 95% SiO2). Silica sand is a granular material and contains quartz, minute amounts of coal, and clay, and it has minerals in it sometimes. It was purchased from a construction site in Lagos State, Nigeria. The sand was purchased dry. The sand of fraction 0.6 to 1 mm was used in the concrete mix at 416 kg/m3. The chemical composition of silica sand is provided in Table 4. The properties of silica include both physical and chemical properties like hardness, color, melting, and boiling point.

i. Silica is a solid crystallized mineral under normal conditions of temperature and pressure and is relatively hard.

ii. Pure silica is colorless, but it may be colored if contaminants are present in a sample of quartz.

iii. Silica has very high melting and boiling points—at 3,110°F and 4,046°F, respectively.

iv. To make glass, it takes a big hot furnace to melt silica.

| Chemicals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | CaO | FeO | Al2O3 | MgO |

| Percentages, % | ||||

| 96.62 | 0.57 | 1.02 | 1.54 | 0.57 |

Source: Murthy and Rao (2016).

Crushed granite as coarse aggregates at 416 kg/m3. The coarse aggregates of crushed granite were obtained from a dealer in Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. Granite of size 5 to 10 mm was used as the coarse aggregate in the concrete. The 416 kg/m3 volume is split according to the variation percentages between granite and periwinkle shells.

Periwinkle shell (PS) as coarse aggregate. The quantity of periwinkle shell taken is equal by volume to that of granite. Periwinkle shells of length 20 mm and diameter 5 mm were used as partial and full replacement for granite in the concrete at 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% replacement. The shells were obtained locally from the Bonny River in Rivers State, Nigeria. The periwinkle shells were obtained after removing the periwinkle meat from the inside of the periwinkle shells manually with the help of a hook, then the shells were soaked in water for 24 h and washed four times in four different sets of drinkable water. After washing, the periwinkle shells were spread on a dry surface at room temperature of 22 ± 5°C and then packed for use. The 416 kg/m3 volume is split according to the variation percentages between granite and periwinkle shells.

Super plasticizer. The superplasticizer used was Sika visco-create 2000 at 14 kg/m3. Sika ViscoFlow®-2000 (GB) is a liquid admixture for concrete based on unique polycarboxylate polymer technologies. Sika ViscoFlow®-2000 (GB) is designed as a high-range water reducer or superplasticizer. It is particularly suited for use in concretes that require low water/cement ratios and/or high-water reductions with excellent workability retention properties of up to 3 h. Sika ViscoFlow®-2000 (GB) meets the requirements of EN 934-2:2009+A1:2012.

Corn starch: The corn starch was procured from a local food vendor in Rivers State, Nigeria. It was dried at a room temperature of 22 ± 5°C to remove moisture content. This is because the batching by mass method was adopted for the experiment. The quantity of corn starch incorporated in the concrete mix is 10.5 kg/m3. The properties of native corn starch used in this study are given in Table 5.

DP denotes the degree of polymerization.

Source: Authors’ own work.

Water. Clean tap water for mixing the concrete aggregates at 277 kg/m3 was used.

For concrete reinforcement, basalt textile also known as basalt fiber cloth or basalt woven textile was used for the concrete confinement.

Basalt textile (BT). BT is a sustainable material obtained by the melting and roving of the raw material known as basalt rock. This material was purchased in Russia. BT is woven from continuous-filament basalt. BT are yarns manufactured to varying thickness, weight, weave pattern, and weaving technique according to end-use requirements with the following properties. The physical and mechanical properties of basalt textiles are indicated in Table 6.

i. Good adhesion characteristics for coatings

ii. Non-combustible and fire-resistant

iii. Excellent tensile strength

iv. Maintains integrity at temperatures up to 982°C

v. Resistant to electromagnetic radiation

vi. BT for high performance.

Source: Naftaros (n.d.).

Experimental procedures

To investigate some of the properties of Lightweight Periwinkle Shell Basalt Textile Confined Concrete (LWPSBTCC), a series of mechanical and physical tests were carried out on the concrete specimens. The tests carried out were slump test, density test, compressive strength test, split tensile test, and water absorption test. They were carried out to determine the workability (W), density (ρ), compressive strength (fc), split tensile strength (fst), and water absorption rate (WAR) of the concrete specimen.

To investigate the properties of this concrete type, 6 (six) concrete mix series were prepared. The coarse aggregate (10 mm fraction size granite) was replaced gradually by volume with periwinkle shells and cast. Due to the replacement, the percentage of granite (G) to periwinkle shells (PS) for each variation that made up the six concrete mix series is shown in Table 7.

Source: Authors’ own work.

This variation was made to determine the percentage replacement value that produced the lightest and strongest mix. A total number of 108 concrete cubes and 180 concrete cylinders were cast from the six concrete mix series. From each of the mix series, 18 concrete cube specimens of dimensions 100 × 100 × 100 mm were cast. Ninety concrete cylinders from the 180 cylinders of 0100 × 100 × 200 mm height were confined in basalt textile (BT) while the other 90 concrete cylinders that were not confined in BT were regarded as control specimens. This was done to accurately determine the effect of BT on the PSLWC. For each of the two sets of concrete cylinders (confined concrete cylinder and non-confined concrete cylinder), 15 concrete cylinders from each of the concrete mix series were prepared and cast. During the batching process, slump tests were carried out on all six concrete mix series to determine the effect of the periwinkle shells on the W of the concrete. The ρ tests were carried out on the concrete cubes 48 h after casting.

The concrete mixes prepared were cast into metallic molds at room temperature (22 ± 5°C). After the concrete mix had been prepared to derive concrete paste for each mix series, some paste samples from each concrete mix series were poured in a slump cone to determine the concrete workability and then the concrete mix was poured inside a metallic mold (cubes and cylinders not confined in BT) based on their individual purposes. After pouring the paste into the cube molds, the individual molds were manually vibrated and then stored in a dry environment in the laboratory at a temperature of 22 ± 5°C. After 24 h from the casting hour, the hardened cubes were removed from the molds and cured in a curing tank until the individual testing day. The aim was to ensure a sufficient bond between the concrete and the basalt textile by ensuring the basalt textile was overlapped for a length equal to 1/3 of the circumference of the cylinder (D’Anna, et al., 2021). Equation (1) was employed to achieve this aim.

(1)

where r is the radius of the cylinder and h is the height of the cylinder.

To achieve the bond between the concrete and the BT, the BT was folded to fit the height of the cylinder and the length of the BT to be inserted inside the cylindrical mold was made to match the circumference of the cylinder plus the overlap length according to equation (2).

(2)

After the BT had been wrapped inside the cylinder mold with the BT length from equation (2), the concrete mixture was poured inside the mold and manual vibration was conducted on it to remove excessive pores. After this, the mold containing the concrete paste was stored in the laboratory at a temperature of 22 ± 5°C for 48 h before removing the hardened cylindrical concrete from the mold. The hardened cylindrical concrete (Figure 4) was stored in a curing bath until the individual testing day. A single layer of BT was used in the confinement.

Figure 4. Periwinkle shell lightweight concrete cylinder confined in basalt textile. Source: Authors’ own work.

For the mechanical properties, the compressive strength (fc) and split tensile strength (fst) were tested. The fc tests were carried out on the concrete cubes and cylinders on days 7, 14, and 28 from the casting day. Three concrete cubes and three concrete cylinders were tested on the respective days for fc. The fst was carried out on days 7 and 28 from the casting day. Three concrete cubes and three concrete cylinders were tested on the respective days for fst. Then, the water absorption of the concrete specimen for each aggregate percentage variation was determined using three cubes. The MoE was then determined for the cubes, the cylinders confined in basalt textile, and the control specimen on day 28 using equation (3) according to ACI 318-19.

(3)

where Ec is the modulus of elasticity in GPa, Wc is its density in kg/m³, and is the square of the compressive strength in MPa.

Results and analysis

The results from the laboratory experiments and the numerical analysis done using the data from the experiments are discussed in this section.

Granite–periwinkle shell concrete workability

Slump tests were conducted on the six different concrete mix series. The variation in the percentages of granite and periwinkle shells is indicated in Table 7. It was discovered in the slump value results (Table 8) that GPS 1 has the highest slump value while GPS 6 has the lowest slump value. From the results, there was a 66.67% reduction in the slump value of the concrete mix series when compared between GPS 1 and GPS 6. The increase in the percentage of periwinkle shells and the decrease in the percentage of granite caused the workability of the concrete to reduce, which is linked to the structural and textural qualities of the periwinkle shell, confirming some research (Agbede and Manasseh, 2009; Eboibi, Akpokodje and Uguru, 2022), which noted that based on the structural and textural qualities of the periwinkle shells, the PS requires more water in the cement to produce workable concrete than smooth and rounded aggregates, which also give PS good bonding properties with the cement and improve the properties of the concrete.

| Percentage variation | GPS 1 | GPS 2 | GPS 3 | GPS 4 | GPS 5 | GPS 6 |

| Slump value (cm) | 7.5 | 6.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 3 | 2.5 |

Source: Authors’ own work.

Granite–periwinkle shell concrete density

Results of the densities of the different concrete mix series are given in Table 9. The densities of the concrete cubes produced with periwinkle shells were affected by the increase in the percentages of PS and the decrease in the percentages of granite. As presented in the results, there is a gradual reduction in the density of the concrete cube specimens as the content of periwinkle shells increased along with the decrease in the percentage of granite. It was observed that the variations GPS 1, GPS 2, and GPS 3 did not achieve the status of LWC but rather fell into the category of normal-weight concrete. This is because its densities were more than 2,000 kg/m³ while the variations GPS 4, GPS 5, and GPS 6 achieved densities of less than 2,000 kg/m³ and therefore can be classified as lightweight concrete according to standards (BS EN 206:2013). The density of concrete mix with GPS 6 was 1,740 kg/m³, which is 22.74% lower than the density of concrete mix with GPS 1. This corresponds with the range identified in the study by Jihad and Ali (2014) where the researchers simply defined LWC as concrete with a dry density of 300 to 2,000 kg/m³ and a cube compressive strength of 1 to 60 MPa. Lightweight periwinkle shell concrete can be used as a replacement for normal concrete. The concrete produced during this experiment falls under the description of lightweight concrete and normal-weight concrete depending on the density. Also, the concrete demonstrated excellent load-bearing capacity.

| Percentage variation | GPS 1 | GPS 2 | GPS 3 | GPS 4 | GPS 5 | GPS 6 |

| Density, kg/m³ | 2,252 | 2,158 | 2,057 | 1,983 | 1,833 | 1,740 |

Source: Authors’ own work.

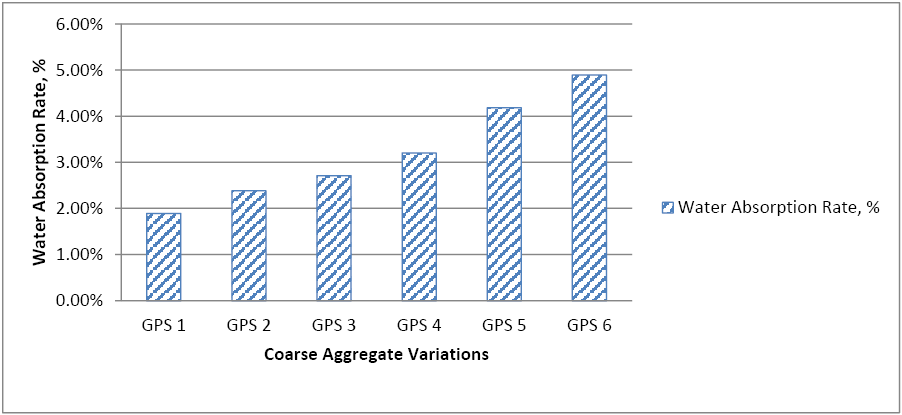

Water absorption

Table 10 and Figure 5 show the rate of water absorption (%) for the concrete cube specimens at different aggregate variations. From the results, it is observed that the rate of water absorption varies depending on the concrete mix. The concrete containing more periwinkle shell, that is, concrete with GPS 5 and GPS 6, has a higher rate of absorption at 4.89% and 4.18%, respectively. The concrete that had lower rates of water absorption were the ones that contained little or no periwinkle shells such as the variations GPS 1 and GPS 2 at 1.89% and 2.38%, respectively. This can be attributed to the texture and structure of the periwinkle shell as noted in the study by Eboibi, Akpokodje and Uguru (2022).

Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 5. Rate of water absorption of concrete cube specimen. Source: Authors’ own work.

Mechanical properties of the granite–periwinkle shell concrete

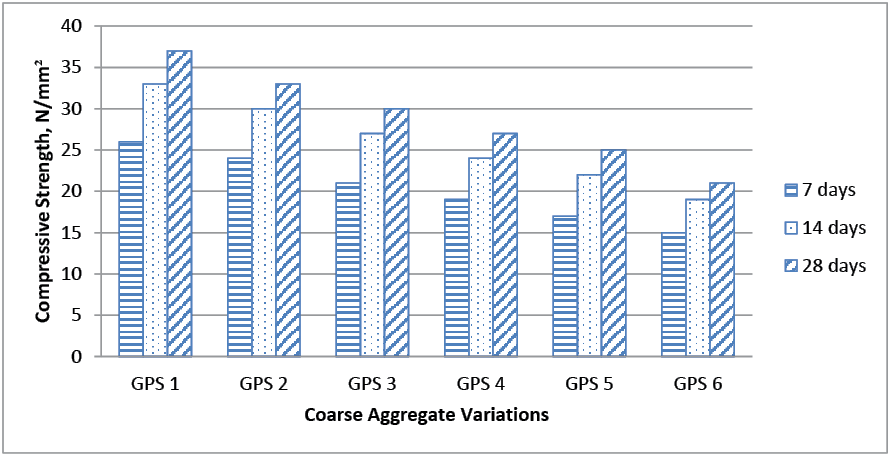

Table 11 shows the compressive strength (fc) and split tensile strength (fst) of the concrete cubes and concrete cylinders confined (wrapped) and not wrapped in basalt textile. The fc tests were conducted on days 7, 14, and 28 after casting while the fst tests were conducted on days 7 and 28 after casting.

Source: Authors’ own work.

Compressive strength of the concrete cubes. Figure 6 displays the relationship between the compressive strength (fc) of the concrete cubes and the percentage variation of aggregates on the 7th, 14th, and 28th days after casting. It is observed that an increase in the quantity of PS replacement of G resulted in a decrease in the fc of the cubes. This is consistent for the 7th, 14th, and 28th days after casting for all coarse aggregate percentage variations in the concrete. It is observed that the concrete mix that obtained the highest strength on the 28th day is GPS 1 at the strength of 37 N/mm2. Among the variations that contain periwinkle shells, the GPS 2 obtained the highest strength of 33 N/mm2 on the 28th day. These results conform with the research study (Aboshio, Shuaibu and Abdulwahab 2018; Dahiru, Yusuf and Paul, 2018).

Figure 6. Compressive strength (N/mm2) against percentage variation (%) for cube specimens. Source: Authors’ own work.

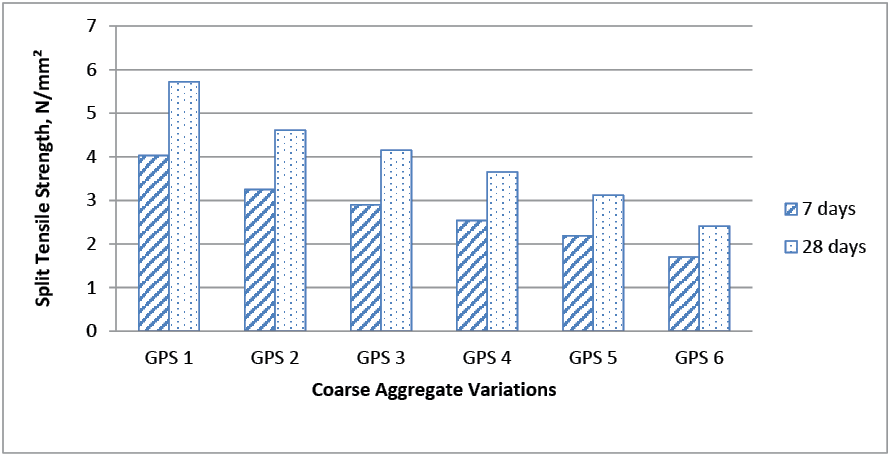

Split tensile strength of the concrete cubes. Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between the split tensile strength (fsts) of the concrete cubes and the different mix variations on the 7th and 28th day after casting. An increase in the quantity of periwinkle shell replacement of granite resulted in the gradual reduction of the fst of the cubes. This is consistent for all testing days after casting for the mix variations. From the results, the concrete mix variation GPS 1, which contains no periwinkle shells, obtained the highest fsts of 6.12 N/mm2. Among the variations that contain periwinkle shells, GPS 2 obtained the highest fsts of 5.58 N/mm2 on the 28th day. The research study by Omisande and Onugba (2020) confirms the results of this study.

Figure 7. Split tensile strength (N/mm2) against percentage variation (%) for cube specimens. Source: Authors’ own work.

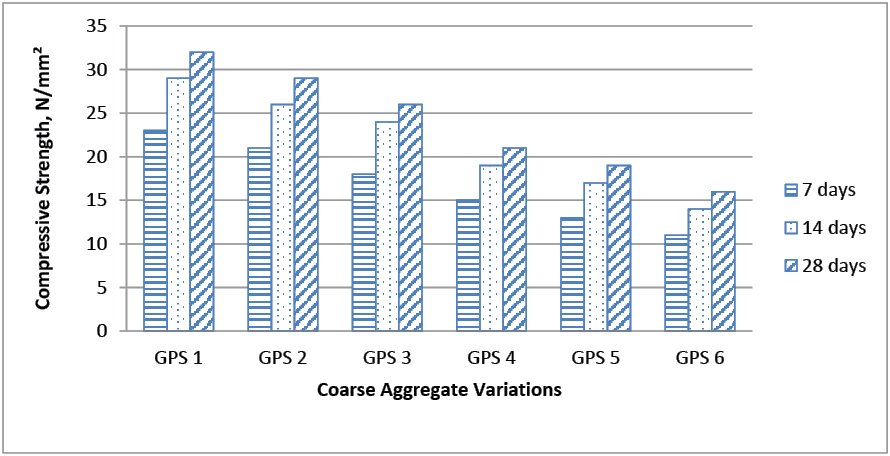

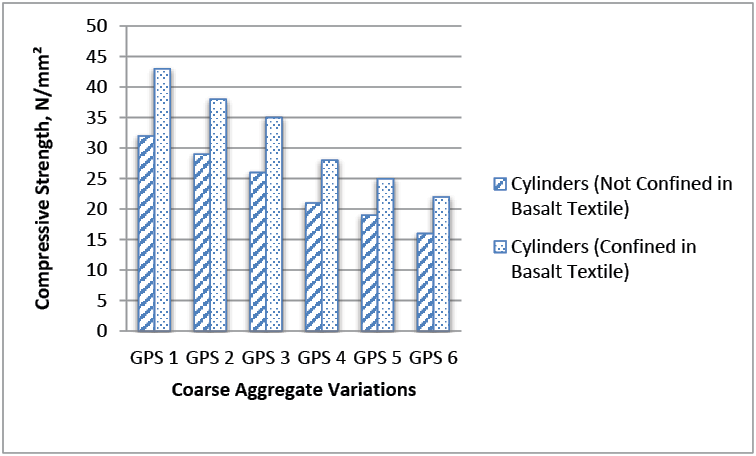

Compressive strength of the concrete cylinders unconfined in basalt textiles. In Figure 8, the fc values of the concrete cylinder control specimen are illustrated. It is observed that the fc of the specimen reduces with the increase of periwinkle shells as a replacement for granite. The variation that achieved the highest fc of 32 N/mm² is GPS 1, which contains no periwinkle shells. The remaining variation achieved fc values of 29, 26, 21, 19, and 16 N/mm2, respectively, with the variation GPS 2 obtaining the highest fc among the variations containing percentages of periwinkle shells. These results conform with those of other research studies (Aboshio, Shuaibu and Abdulwahab 2018; Dahiru, Yusuf and Paul, 2018).

Figure 8. Compressive strength (N/mm2) against percentage variation (%) for cylinders without confinement (control specimens). Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 9 shows the pattern at which the concrete cylinder not confined in basalt textile failed under compressive test. It is observed that the concrete did not show much noticeable fatigue, but a gradual crack cut growth.

Figure 9. Failure pattern of the basalt textile not confined concrete cylinder under compressive test. Source: Authors’ own work.

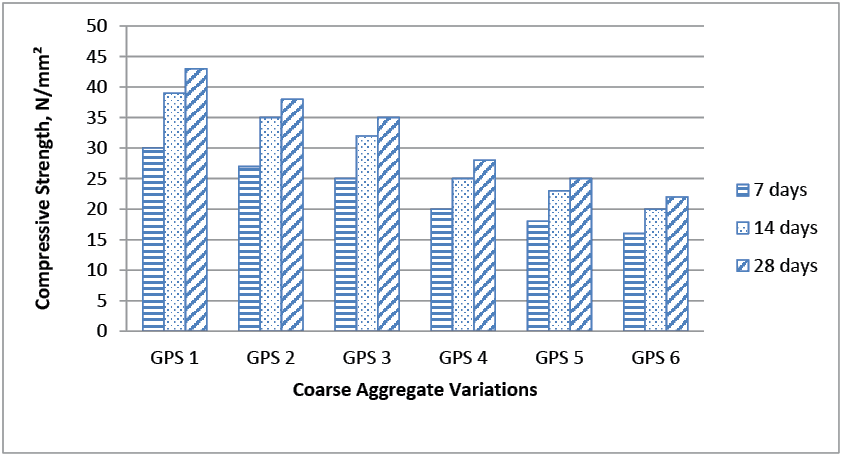

Compressive strength of concrete cylinders confined in basalt textile. The fc values of the concrete cylinders confined in BT are illustrated in Figure 10. This was done to show the relationship between the aggregate percentage variations and the fc. It was observed that the fc of the concrete specimens reduced gradually as the percentage of PSs increased. It was also observed that the concrete increased in fc on the 7th, 14th, and 28th day after casting. This increase was seen in variations of the concrete mix. The variation that obtained the highest fc was the GPS 1, which contained no periwinkle shells. Among the variations containing periwinkle shells, the specimen with GPS 2 obtained the highest fc of 43 N/mm2. The variation that obtained the lowest fc was the variation GPS 6 with a compressive strength of 22 N/mm2. These findings support the results of the study by Zhang, et al. (2023), which stated that confining basalt textile on concrete improved the compressive strength of the concrete.

Figure 10. Compressive strength (N/mm2) against percentage variation (%) for cylinders confined in basalt textile. Source: Authors’ own work.

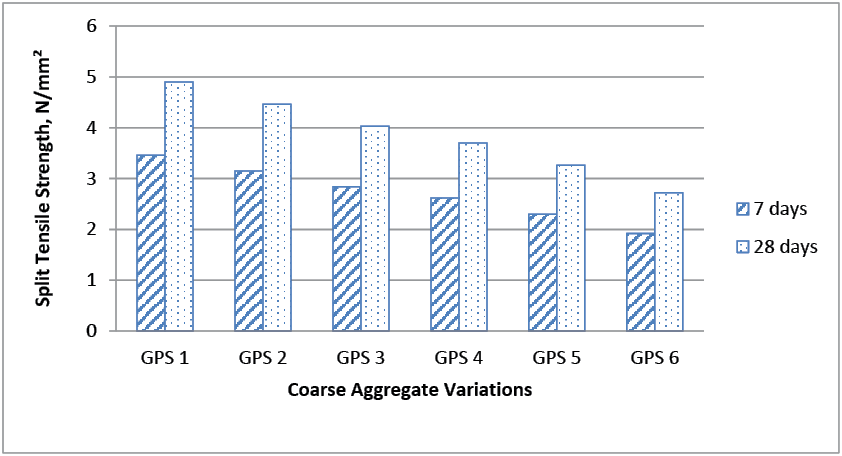

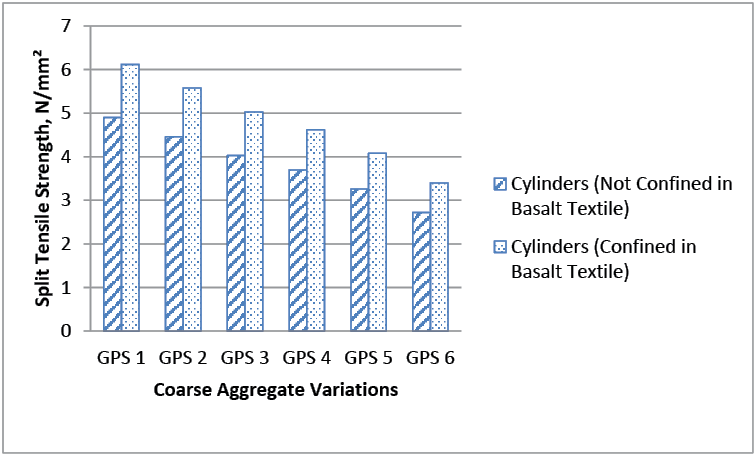

The split tensile strength of the concrete cylinders unconfined in basalt textiles. Figure 11 shows the relationship between the fsts and the aggregate percentage variation of the concrete cylinders not confined to basalt textiles. It was observed that there was a gradual decrease in the fsts of the concrete cylinders as the percentage of PSs increased. This trend is consistent for both the 7th and 28th day after casting. For the variations GPS 1, GPS 2, GPS 3, GPS 4, GPS 5, and GPS 6, the fsts obtained was 4.9, 4.46, 4.03, 3.7, 3.26, and 2.72 N/mm2 respectively. The study by Omisande and Onugba (2020) confirms the results of this study.

Figure 11. Split tensile strength (N/mm2) against percentage variation (%) for cylinders without confinement (control specimen). Source: Authors’ own work.

Split tensile strength of the concrete cylinders confined with basalt textile. Figure 12 shows the failure pattern of the concrete cylinder confined basalt textile where the concrete did not split completely, and the cut developed gradually. During the failure of the specimen under the split tensile test, it was observed that the main crack became wider on one side than the other, resulting in the specimen failure.

Figure 12. Failure pattern of the basalt textile-confined concrete under tensile test. Source: Authors’ own work.

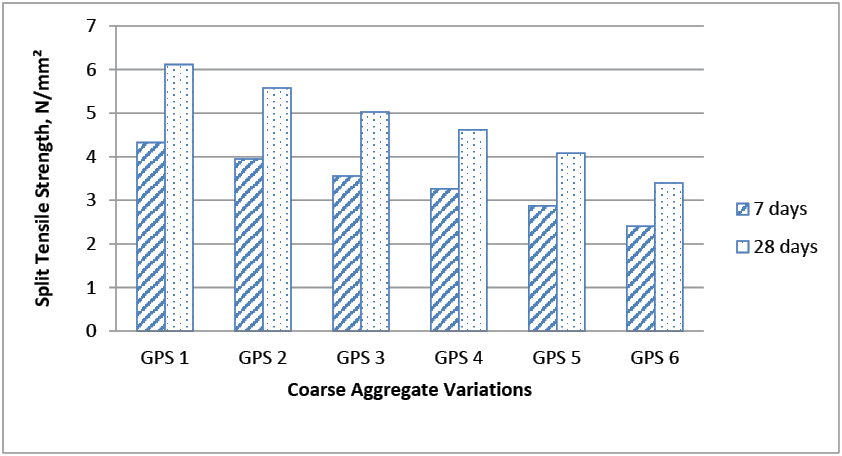

The fst of the concrete confined in BT on the 7th and 28th day after casting are illustrated in Figure 13 for all variations of the aggregate percentages. The fst of the concrete cylinders reduced with an increase in the replacement of granite with periwinkle shells. The GPS 1 variation obtained the highest fst of 6.12 N/mm2 while the GPS 6 variation obtained the lowest fst of 3.4 N/mm2. The variation containing periwinkle shells that obtained the highest fst on the 28th day after casting is GPS 2 with a value of 5.58 N/mm2. The research results presented in the study conducted by Zhang, et al. (2023) support the results of this current study.

Figure 13. Split tensile strength (N/mm2) against percentage variation (%) for cylinders confined in basalt textile. Source: Authors’ own work.

To understand the effect of BT on the strength of the different concrete mix series in hardened concrete cylinders, comparisons of the fc and fsts are given in Table 12 and Figure 14 for fc and in Table 13 and Figure 15 for fsts.

Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 14. Comparison of compressive strength of cylinders (control specimen) and cylinders confined in basalt textile on day 28. Source: Authors’ own work.

Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 15. Comparison of split tensile strength of concrete cylinder (control specimen) and cylinders confined in BT. Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 14 shows the fc comparing the concrete cylinder confined and unconfined in BT at 28 days. The comparison is done for the cylinders for all the variations of the concrete mix. It was observed that the concrete cylinders confined in BT obtained a considerably higher fc than the concrete cylinders unconfined in BT (control specimen). The percentage increases in the fc of the cylinders confined in BT are given in Table 12. From the table, the aggregate percentage variations GPS 1, GPS 2, GPS 3, GPS 4, GPS 5, and GPS 6 experienced a 34, 31, 34, 42, 31.5, and 37.5 percentage increase of the fc for the concrete cylinders confined in BT as compared to the control specimen (concrete cylinder unconfined in BT), respectively.

Figure 15 shows a comparison of the fsts of the concrete control specimen cylinders and concrete cylinders confined in BT. The comparison is done for all the variations of the concrete mix on the 28th day after casting. From the figure, it is observed that the cylinders confined in BT obtained a higher fsts than the control specimen. The percentage increases in fsts of the cylinders confined in BT are shown in Table 13. From the table, the aggregate percentage variations GPS 1, GPS 2, GPS 3, GPS 4, GPS 5, and GPS 6 experienced a 24.9, 25.11, 24.81, 24.86, 25.15, and 25 percentage increase in the fsts of the cylinders confined in BT as compared to the control specimen, respectively.

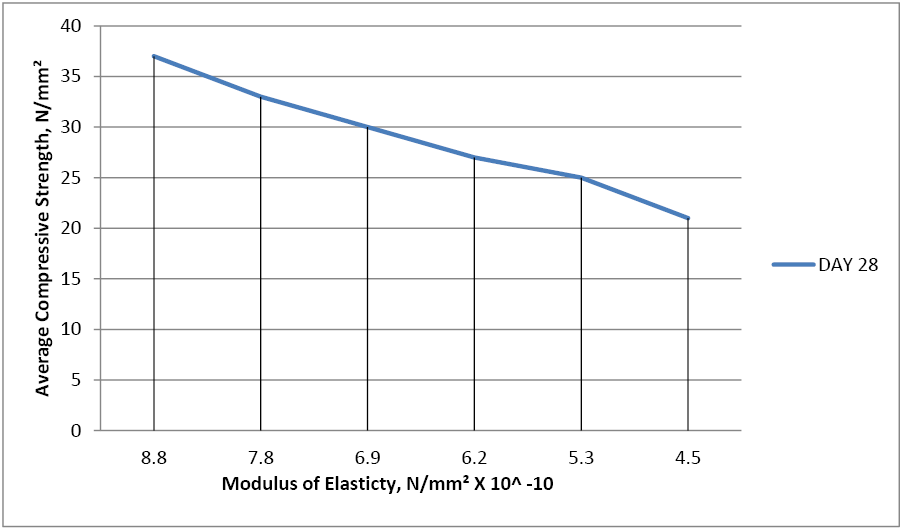

Modulus of elasticity

To determine the modulus of elasticity, equation (3) was solved for concrete mix bearing their individual coarse aggregate variation percentages. Hence, Table 14 and Figure 16 show the MoE of concrete cube specimens, while Table 15 shows the MoE of the concrete cylinders all at different coarse aggregate variation percentages.

Source: Authors’ own work.

Figure 16. Relationship graph between average compressive strength (N/mm²) and modulus of elasticity (N/mm²) of cubes. Source: Authors’ own work.

Source: Authors’ own work.

The modulus of elasticity against fc of concrete cube specimens on the 28th day after casting is illustrated in Figure 16. From the graph plotted, it is observed that a reduction in the fc of the concrete resulted in a reduction of the modulus of elasticity, indicating that the growth in the percentages of periwinkle shells with a decrease in the percentages of granite caused the reduction in the modulus of elasticity. The results of the modulus of elasticity obtained in this study conform to the analysis of previous research (Ahsan, et al., 2022; Zhu, et al., 2024).

The densities and MoE of concrete cylinders are presented in Table 15. The data show that the concrete cylinder that obtained a lower fc also obtained lower density and MoE. The observable trend from the results is that with a decrease in the fc of the concrete cylinders, there was a decrease in the density and MoE of the respective concrete cylinders. The MoE percentage increases of each unconfined concrete cylinder to BT-confined concrete cylinder are given in Table 15. Concrete cylinders with variation percentages of GPS 6 had the highest increase of MoE between the control specimen and the BT-confined concrete at 17.9%. According to the experimental study by Chiadighikaobi, et al. (2022), confining concrete in basalt fiber-reinforced polymer improved the modulus of elasticity of the concrete, which conforms with the results of this current study.

Economic impact of the use of basalt textile and periwinkle shell on managing the construction of concrete structures in Nigeria

Basalt textile compared to conventional steel reinforcement

The potential and properties of basalt textiles have been established in literature reviews and in this study. Basalt textile originates from a volcanic rock known as basalt rock. The production process of basalt textile is free from any additives and it is ecologically friendly. The cost of basalt materials is cheaper than that of steel materials (Adejuyigbe, Chiadighikaobi and Okpara, 2019).

Our rationale for proposing basalt is that due to the numerous industrial functions that have contributed to environmental pollution worldwide, including the fusion that results from the production of structural steel, sustainable and environmentally friendly materials that are better able to lower the rate of environmental pollution should be considered when replacing older ones.

In the event of a disaster like an earthquake, the rate at which structures will sustain damage can be reduced by using basalt textiles as reinforcement in concrete. This capability represents a cost–benefit innovation that can promote sustainable environmental practices in structures by enabling better structural repair.

Periwinkle shell compared to granite and crushed stone

Natural aggregates are expected to run out soon due to the building industry’s rapid expansion, which will drive up the price of concrete materials. Because of the inadequacy of these traditional building materials—granite, crushed stone, cement, etc.—and the fact that local demand for these materials far outpaces local supply, the cost of construction projects in Nigeria—such as buildings, roads, pavements, etc.—has been steadily rising.

Waste is generally of lesser economic value unless recycled. Hence, periwinkle shell, a by-product readily available locally and with little economic value, has a greater economic impact in concrete production than conventional concrete coarse aggregates. Using periwinkle to make concrete lowers production costs while conserving natural resources and safeguarding the environment. The experimental analysis conducted in this study has proven that using periwinkle shells in concrete reduces the density of the concrete, hence creating a lightweight concrete that has a greater positive economic impact than the normal-weight concrete.

Furthermore, the cost analysis showed that using 100% periwinkle shell as a coarse aggregate would result in a cost saving of 24%, and using 30% instead of granite as a coarse aggregate would result in a cost saving of 6.8% (Soneye, et al., 2016).

Conclusions

From the experimental study and analysis, it was discovered that:

1. The results from the slump tests revealed that the concrete mix series with 100%G and 0%PS had more slump value while 0%G and 100%PS had the lowest slump value. This shows that the increase in the quantity of periwinkle and the decrease in the quantity of granite caused a reduction in the workability of the concrete. This conforms with research reports (Agbede and Manasseh, 2009; Eboibi, Akpokodje and Uguru 2022) that noted that based on the structural and textural qualities of the periwinkle shells, the PS requires more water in the cement to produce workable concrete than smooth and rounded aggregates, which also give PS good bonding properties with the cement and improve the properties of the concrete.

2. As the percentages of periwinkle shells increase with a decrease in the percentages of granite in the concrete series, the density of the concrete is reduced. This corresponds with the range identified in Jihad and Ali (2014), where the researchers simply defined LWC as concrete with a dry density of 300 to 2,000 kg/m³ and a cube compressive strength of 1 to 60 MPa.

3. The durability of the concrete was checked by analyzing the rate of water absorption. It was discovered that an increase in the percentage of periwinkle shells and a decrease in the percentage of granite increased the rate of water absorption. Hence, GPS 1 had the lowest rate of water absorption, while GPS 6 had the highest rate of water absorption at 1.89% and 4.89%, respectively. This can be attributed to the texture and structure of the periwinkle shell, as noted in the study by Eboibi, Akpokodje and Uguru (2022).

4. During this research study, the mechanical properties of lightweight periwinkle shell concrete confined in basalt textiles were investigated and determined. Through a series of mechanical tests, the mechanical properties were obtained and analyzed to determine the suitability of the concrete for construction. It was discovered that as the percentages of the periwinkle shells increased with the decrease in the percentages of granite, the compressive strength of the concrete decreased and these results conform with Aboshio, Shuaibu and Abdulwahab (2018), while the split tensile strength of the concrete decreased under the same condition as the compression tests. The research by Omisande and Onugba (2020) confirms the results of this current study. When the concrete cylinders were wrapped with basalt textile, the hardened concrete’s compressive strength and split tensile strength increased. This supports the findings of the study by Zhang, et al. (2023).

5. This study showed a decrease in the modulus of elasticity of the concrete as the percentages of the periwinkle shells increased while the percentages of granite decreased. The modulus of elasticity obtained in this study supports the analysis of previous research (Zhu, et al., 2024; Ahsan, et al., 2022). However, when concrete was wrapped with basalt fiber textile, an increase in the modulus of elasticity was achieved on the individual hardened mix series. This supports the findings of Chiadighikaobi, et al. (2022).

According to the results obtained in this study, it can be concluded that the periwinkle shell concrete produced with periwinkle shells can be labeled as lightweight concrete depending on the amount of granite replaced. Furthermore, it was determined that the PSLC did not attain a higher compressive and split tensile strength than normal aggregate concrete. Regardless, its strength still makes it applicable for construction purposes. The effects of basalt textile on the PSLC were also found to be beneficial, as it increased the load-bearing capacity of the concrete. PSLC is suitable for structural construction, and the study determined that periwinkle shells can be used to produce structural LWC, where an analysis of the possibility of producing LWC with periwinkle shells was given.

The adoption of use of periwinkle shells will result in the reduction of the use of natural resources and provide a method of disposal for the periwinkle shells that heavily litter the environment. Moreover, by adopting the use of PSLC confined in basalt textiles, another avenue for its use is obtained. This is because concrete confined in basalt textile can be used for the repair of structures. It would be beneficial to both the economy and the environment to embrace this concrete to promote the development and construction of sustainable infrastructure in Nigeria due to the economic and structural potentials of BT and PS on the concrete.

Acknowledgments

This research and publication did not receive any funding.

References

Aboshio, A., Shuaibu, H.G. and Abdulwahab, M.T., 2018. Properties of rice husk ash concrete with periwinkle shell as coarse aggregates. Nigerian Journal of Technological Development, 15(2), p.33. https://doi.org/10.4314/njtd.v15i2.1

ACI Committee 318, 2019. ACI 318-19: Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary, USA.

Adejuyigbe, I.B., Chiadighikaobi, P.C. and Okpara, D.A., 2019. Sustainability comparison for steel and basalt fiber reinforcement, landfills, leachate reservoirs and multi-functional structure. Civil Engineering Journal, [online] 5(1), pp.172–180. https://doi.org/10.28991/cej-2019-03091235

Agbede, O.I. and Manasseh, J., 2009. Suitability of periwinkle shell as partial replacement for river gravel in concrete. Leonardo Electronic Journal of Practices and Technologies, 15(2), pp.59-66

Ahsan, M.H., Siddique, M.S., Farooq, S.H., Usman, M., Ul Aleem, M.A., Hussain, M. and Hanif, A., 2022. Mechanical behavior of high-strength concrete incorporating seashell powder at elevated temperatures. Journal of Building Engineering, [online] 50, p.104226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104226

Akadiri, P.O., Chinyio, E.A. and Olomolaiye, P.O., 2022. Design of a sustainable building: a conceptual framework for implementing sustainability in the building sector. Buildings, [online] 2(2), pp.126–152. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings2020126

Alexander, A.E. and Shashikala, A.P., 2020. Sustainability of construction with textile reinforced concrete-a state of the art. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 936(1), p.012006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/936/1/012006

Aliyu, S.I., Kwami, I.A. and Sani, A., 2022. Developed prediction models for compressive strength of periwinkle shell concrete using ultrasonic pulse velocity test. African Journal of Advanced Sciences and Technology Research, 4(1), pp.39-49. https://publications.afropolitanjournals.com/index.php/ajastr/article/view/157/94

Althoey, F., Ansari, W.S., Sufian, M. and Deifalla, A. F., 2023. Advancements in low-carbon concrete as a construction material for the sustainable built environment. Developments in the Built Environment, 16, 100284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100284

ASTM International [ASTM], 2017. Standard specification for lightweight aggregates for structural concrete (ASTM C330/C330M17A). West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International

Backes, J.G. and Traverso, M., 2021. Application of Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment in the Construction Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. Processes, 9(7), p.1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9071248

BS EN 197-1, 2011. Cement. Composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements.

BS EN 206, 2013. Concrete - specification, performance, production and conformity (+A2:2021).

Chalioris, C.E., Papadopoulos, C.D., Pourzitidis, C.N., Fotis, D. and Sideris, K.K., 2013. Application of a reinforced self-compacting concrete jacket in damaged reinforced concrete beams under monotonic and repeated loading. Journal of Engineering, 2013, 912983. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/912983

Chiadighikaobi, P.C., Muritala, A.A., Abu Mahadi, M.I., Abd Noor, A.A., Ibitogbe, E.M., & Niazmand, A.M., 2022. Mechanical characteristics of hardened basalt fiber expanded clay concrete cylinders. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 17, e01368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01368

Choi, J., 2019. Strategy for reducing carbon dioxide emissions from maintenance and rehabilitation of highway pavement. Journal of Cleaner Production, 209, pp.88–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.226

Chowdhury, I.R., Pemberton, R. and Summerscales, J., 2022. Developments and industrial applications of basalt fibre reinforced composite materials. Journal of Composites Science, 6(12), p.367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs6120367

D’Anna, J., Amato, G., Jian Fei Chen, Minafò, G. and Lidia La Mendola., 2021. Experimental investigation on BFRCM confinement of masonry cylinders and comparison with BFRP system. Construction and Building Materials, 297, 123671–123671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123671

Dahiru, D., Yusuf, U.S. and Paul, N.J., 2018. Characteristics of concrete produced with periwinkle and palm kernel shells as aggregates. FUTY Journal of the Environment, 12(1), pp.42-61.

Dauda, A.M., Akinmusuru, J.O., Dauda, O.A., Durotoye, T.O., Ogundipe, K.E. and Oyesomi, K.O., 2018. Geotechnical properties of lateritic soil stabilized with periwinkle shells powder. International Journal Civil Engineering Technology, 10, pp.2014–2025. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201811.0100.v1

Eboibi, O., Akpokodje, O.I. and Uguru, H., 2022. Evaluation of organic enhancer on the mechanical properties of periwinkle shells concrete. Journal of Engineering Innovations and Applications, 1(1), pp.13-22. https://doi.org/10.31248/JEIA2022.020

Ede, A.N., Gideon, P.O., Akpabot, A.I., Oyebisi, S.O., Olofinnade, O.M. and Nduka, D.O., 2021. Review of the properties of lightweight aggregate concrete produced from recycled plastic waste and periwinkle shells. Key Engineering Materials, 876, pp.83–87. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.876.83

Elegbede, I.O., Lawal-Are, A., Oloyede, R., Sanni, R.O., Jolaosho, T.L., Goussanou, A. and Ngo-Massou, V.M., 2023. Proximate, minerals, carotenoid and trypsin inhibitor composition in the exoskeletons of seafood gastropods and their potentials for sustainable circular utilisation. Scientific Reports, [online] 13(1), p.13064. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38345-w

Emeghai, J.C. and Orie, O.U., 2021. Mechanical properties of concrete with agricultural waste as a partial substitute for granite as coarse aggregate. Pakistan Journal of Engineering and Technology, 4(2), pp.5-12. https://doi.org/10.51846/vol4iss2pp5-12

Emiero, C. and Oyedepo, O.J., 2012. An investigation on the strength and workability of concrete using palm kernel shell and palm kernel fibre as a coarse aggregate. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 3(4), pp.1-5.

EN 934-2:2009+A1:2012(MAIN). Admixtures for concrete, mortar and grout - Part 2: Concrete admixtures - Definitions, requirements, conformity, marking and labelling.

Eziefu, U.G., Opara, H.E. and Anya, C.U., 2017. Mechanical properties of palm kernel shell concrete in comparison with periwinkle shell concrete. Malaysian Journal of Civil Engineering, 29(1), pp.1-14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318590102_Mechanical_properties_of_palm_kernel_shell_concrete_in_comparison_with_periwinkle_shell_concrete https://doi.org/10.11113/mjce.v29.15585

Falade, F., Ikponmwosa, E.E., and Ojediran, N.I., 2010. Behaviour of lightweight concrete containing periwinkle shells at elevated temperature. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 5(4), pp.379–390.

Gopinath, S., Murthy, A.R., Iyer, N.R. and Prabha, M., 2015. Behaviour of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with basalt textile reinforced concrete. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 44(6), pp.924-933. https://doi.org/10.1177/1528083714521068

ICED, n.d. Construction Sector Employment in Low-Income Countries: Size of the Sector. [online] Available at: http://icedfacility.org/resource/construction-sector-employment-low-income-countries-size-sector/

Ifeanyi, O.E., Chima, A.D. and Chukwudubem, N.J., 2023. Structural behavior of concrete produced using palm kernel shell (PKS) as a partial substitute for coarse aggregate. American Journal of Innovation in Science and Engineering, 2(1), pp. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.54536/ajise.v2i1.1228

Isang, I.W., 2023. A historical review of sustainable construction in Nigeria: a decade of development and progression. Frontiers in Engineering and Built Environment, 3(2), pp.1-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/FEBE-02-2023-0010

Jihad, H.M. and Ali, J.H., 2014. A classification of lightweight concrete: materials, properties and application review. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Applications, 7(1), pp.52-57.

Kaja, N. and Goyal, S., 2023. Impact of construction activities on environment. International Journal of Engineering Technologies and Management Research, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.29121/ijetmr.v10.i1.2023.1277

Koutas, L.N. and Bournas, D.A., 2020. Confinement of masonry columns with textile-reinforced mortar jackets. Construction and Building Materials, 258, p.120343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120343

Kumbhar, V.P., 2014. An overview: basalt rock fibers-new construction material. Acta Engineering International, 2(1), pp.11-18.

Liu, S., Wang, X., Rawat, P., Chen, Z., Shi, C. and Zhu, D., 2021. Experimental study and analytical modeling on tensile performance of basalt textile reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 267, p.120972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120972

Mahmoud, K.M., Sallam, E.A. and Ibrahim, H.M.H., 2022. Behavior of partially strengthened R.C. columns from two or three sides of the perimeter. Case Studies in Construction Materials, e01180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01180

Manjunatha, M., Preethi, S., Malingaraya, Mounika, H.G., Niveditha, K.N. and Ravi., 2021. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of concrete prepared with sustainable cement-based materials. Materials Today: Proceedings., 47, pp.3637–3644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.248

Mavi, R.K., Gengatharen, D., Mavi, N.K., Hughes, R., Campbell, A. and Yates, R., 2021. Sustainability in Construction Projects: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, [online] 13(4), p.1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041932

Mohammed, J.H. and Hamad, A.J., 2014. Materials, properties and application review of lightweight concrete. Technical Review of the Faculty of Engineering University of Zulia, 37(2), pp.10-15.

Mujalli, M.A., Dirar, S., Mushtaha, E., Hussien, A. and Maksoud, A., 2022. Evaluation of the tensile characteristics and bond behaviour of steel fibre-reinforced concrete: an overview. Fibers, 10(12), p.104. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib10120104

Mukhopadhyay, S. and Shruti K., 2015. A review on the use of fibers in reinforced cementitious concrete. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 45(2), p.239–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1528083714529806

Murthy, I.N. and Rao, J.B., 2016. Investigations on physical and chemical properties of high silica sand, Fe-Cr slag and blast furnace slag for foundry applications. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 35, pp.583–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2016.07.045

Naftaros, n.d. Basalt fibers, fabrics, mesh. Available at: http://naftaros.ru/articles/21/index.html (Accessed: 24th May, 2023)

Natarajan, E., Sekar, S.M., Markandan, K., Ang, C.K. and Franz, G., 2024. Tailoring basalt fibers and E-Glass fibers as reinforcements for increased impact resistance. Journal of Composites Science, 8(4), pp.137–137. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs8040137

Nilimaa, J., 2023. Smart materials and technologies for sustainable concrete construction. Developments in the Built Environment, 15, p.100177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100177

Nwachukwu, O., 2024. (NESREA) and the challenges of environmental regulation in Nigeria. British Journal of Mass Communication and Media Research, 4(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.52589/BJMCMR-FLJQLR8S

Odeyemi, S.O., Abdulwahab, R., Adeniyi, A.G. and Atoyebi, O.D., 2020. Physical and mechanical properties of cement-bonded particle board produced from African balsam tree (Populous Balsamifera) and periwinkle shell residues. Results in Engineering, 3, p.100126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2020.100126

Ogundipe, K.E., Ogunbayo, B.F., Olofinnade, O.M., Amusan, L.M. and Aigbavboa, C.O., 2021. Affordable housing issue: experimental investigation on properties of eco-friendly lightweight concrete produced from incorporating periwinkle and palm kernel shells. Results in Engineering, 9, p.100193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2020.100193

Ogunkan, D.V., 2022. Achieving sustainable environmental governance in Nigeria: a review for policy consideration. Urban Governance, 2(1), pp.212–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ugj.2022.04.004