Construction Economics and Building

Vol. 22, No. 4

December 2022

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Examination of the Communication Strategy Based on Company Straplines: A Case Study of German Construction Companies

Peter Schnell

Institute of Construction Management, University of Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 7, Germany, peter.schnell@ibl.uni-stuttgart.de

Corresponding author: Peter Schnell, Institute of Construction Management, University of Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 7, Germany, peter.schnell@ibl.uni-stuttgart.de

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v22i4.8078

Article History: Received 29/01/2022; Revised 16/08/2022; Accepted 12/09/2022; Published 15/12/2022

Abstract

A target group-oriented communication strategy is decisively responsible for a company’s success. Consequently, addressing the potential target group in all communication sectors could enable a valuable competitive advantage. To verify if companies within the German construction industry follow this theory, a study was conducted. In this study, the communication strategy of the 50 largest German construction companies was examined, based on their company straplines. The following article presents the results. As a research method, both a content analysis was conducted and the basic principles of the “Zurich Model of Social Motivation” of psychologist Norbert Bischof and the archetype theory based on Carl Gustav Jung were applied. The current challenges in the construction industry require a high focus on customer-centricity and collaboration. The study revealed that most of the analysed company straplines are addressed rather to the competitors than to the customers and partners. As a result, the straplines should be rethought and adapted to the customers’ needs and current market requirements.

Keywords

Communication Strategies; Marketing of Construction Companies; Archetypes in the German Construction Industry; Strapline Analysis of Construction Companies

Introduction

As a result of the Corona pandemic in Germany, competition in the construction industry has further intensified. Construction companies are currently facing increasing business rivalry (Welter and Luban, 2022). Therefore, customer acquisition is more difficult and must be carried out uniformly in all parts of the company. As a result, acquisition experts are increasingly in demand. However, at the same time, the shortage of qualified workers and the number of job advertisements, especially for apprentices, is increasing (Bahr and Laszig, 2021; Soka-Bau, 2020). Brucker Juricic, Galic and Marenjak (2021) note that Germany has the most job vacancies each year across Europe. A literature search has shown that there are various reasons for this shortage. A study by Bahr and Laszig (2021) shows that the shortage of qualified workers and the average age is rising mainly because of the lack of young labourers. Nowadays, especially these employees have the expectation and need to identify more with their job or the final product of their work (Gabrielova and Buchko, 2021; Leslie, et al, 2021). The increasing importance of work identity over the last decade is also highlighted in the literature review by Miscenko and Day (2015). The increasing need for qualified workers, especially in the field of acquisition, and the current shortage of these workers shows the necessity to review the communication strategy of German construction companies.

As buildings are a piece of planned work that is completed over a period of time and intended to achieve a particular aim, they are products by definition (Cambridge University Press, 2022). In contrast to other industries, such as the automotive industry, the final products in the construction industry do not embody the brand’s corporate identity. For example, a product built by the car manufacturer Land Rover is predominantly attributed with a “discovery feeling”. This perception of brand identity is accomplished by both specific design characteristics and targeted corporate communication (Jaguar Land Rover Limited, 2022). In the construction business, buildings only slightly reflect the character of the customer, the building owner, or the operator. This applies to both the business-to-business (B2B) and the business-to-customer (B2C) building business. Therefore, buildings do not function directly as advertising objects and do not represent touchpoints with potential customers (Esch, et al., 2016). Only by an action, such as research by interested parties, the product ‘building’ is perceived as a reference.

Thus, the brand character of construction companies is rather shaped by the communication strategy of the companies than by the created buildings. Accordingly, the communication strategies of construction companies must be geared even more towards the target group. However, the predominant problem of the construction industry is that often no specific target groups are defined. In this case, customer characteristics cannot be considered in the communication strategy. It is ambiguous whether the current communication strategies of the key construction companies simply reflect their self-perception or whether the communication strategies successfully reach the target groups. A target group-oriented communication strategy is decisive for the company’s success and can thus represent a valuable competitive advantage (Zerfaß, et al., 2018).

Shlepneva and Maletina (2021) note that marketing is an important element in the activities of a construction company. In construction companies, marketing is predominantly seen as the marketing of a product or project, whereas the communication strategy is not considered (e.g., Drugova, et al., 2021; Shlepneva and Maletina, 2021). However, marketing is currently either misunderstood or neglected in many construction companies as Mokhtariani, Sebt and Davoudpour (2017) describe. Moreover, the nature of the industry often makes it difficult to easily adapt marketing theories and techniques (e.g., Yisa, Ndekugri and Ambrose, 1995; Polat, 2010). The number of studies that attempt to apply traditional marketing theories is very small. (e. g. Dikmen, Talat Birgonul and Ozcenk, 2005; Arditi, Polat and Makinde, 2008; Polat, 2010; Polat and Donmez, 2010). Despite the awareness of the importance of marketing, few studies specifically address the characteristics of marketing in the construction industry (Mokhtariani, Sebt and Davoudpour, 2017). The study by Mokhtariani, Sebt and Davoudpour (2017) is worth mentioning here, who on the one hand investigated the marketing character of the construction industry and on the other hand developed a reference framework for construction marketing. Furthermore, there are no known studies that methodically apply Carl Gustav Jung´s archetype theory or the “Zurich Model of Social Motivation” of psychologist Norbert Bischof to the construction industry.

Literature Review

Communication strategy and corporate communication

The corporate identity of a company serves to convey an image or the company’s brand character to the public (Winkelmann, 2012). Corporate identity can be divided into the areas of corporate behaviour, corporate design, and corporate communication. Corporate behaviour comprises the rules of conduct for employees. Corporate design serves to create a uniform image of the company. Corporate communication is the implementation of the corporate identity, especially the corporate design, by various communication instruments (Berndt, 2005). According to Zerfaß, et al., a significant part of the strategic success of a company can be attributed to corporate communication because it is the only direct link between the brand and the customer (Zerfaß, et al., 2018). The communication strategy is therefore fundamental for the achievement of corporate goals and is considered an important and decisive success factor, which is essential for sustainable customer awareness.

Berndt (2005) has observed that in addition to the conviction of the product itself, the name, the logo, the strapline, and the packaging design must be coordinated and aptly designed for successful positioning. A strapline represents the culture, identity and personality of a brand and therefore is a key component of corporate communication. The strapline should convey descriptive and emotional content to increase awareness. A holistic and consistent use is advantageous (Berndt, 2005). In contrast to company names and logos, straplines are questioned and revised in shorter intervals. For these reasons, the study focuses on the comparison and analysis of straplines. Likewise, no further consideration is given to the packaging design due to the general conditions of the construction industry.

Archetype theory and human motive systems

Through communication tools such as the company strapline, the customers’ awareness and needs are triggered, and certain behaviours are evoked (Scheier and Held, 2018). The Zurich model of psychologist Norbert Bischof identifies three motivational systems - the security system, the arousal system, and the autonomy system (Bischof, 2020; Schneider, 2001). A high level of one system implies a lower level of the others. The perception of products and brands is determined by the individual characteristics of the motivational systems of the respective customers. Accordingly, it is imperative to adapt the communication strategy with specific communication instruments to the customers. For this purpose, comprehensive knowledge of the target group is indispensable. In developing the Zurich model, the disciplines of behavioural research, brain research, and psychology were integrated among others. Today, the model serves as the basis for further research, such as the Limbic Map by Hans-Georg Häusel, which is extensively disseminated in the marketing practice (Scheier and Held, 2018). Likewise, the archetype theory according to Carl Gustav Jung correlates with the motivational systems developed by Norbert Bischof (Jung, 1968).

Archetypes are defined as characters that are always described with the same emotions and behaviour, regardless of the observer. The 12 Jungian archetypes were developed to describe these different behavioural patterns. Although the archetype theory according to Carl Gustav Jung has been criticised in the past, since 2000 many marketing science theories regarding brand personalities and positioning approaches are predominantly based on it (Balmer, 1972; Holzhey-Kunz, 2002; Roesler and Vogel, 2016). The first internationally recognised model related to the Jungian archetypes appeared in 2001. Mark and Pearson applied the theory to the topic of brand management which served as a basis for many subsequent models (Mark and Pearson, 2001). In 2018, Pätzmann and Hartwig developed the currently most promising model which focuses on the adaptation of gender-neutral and contemporary terms for individual archetypes and reinforced its practical application (Pätzmann and Adamczyk, 2020). The archetypes which were used for the present study are based on the model according to Pätzmann and Hartwig and supplemented with Norbert Bischof’s motive systems (Pätzmann and Hartwig, 2018).

Amplifiers are groupings of archetypes in which the same motivational system is most pronounced. Since straplines are intended to stimulate the motivational systems positively, only the positive amplifiers are used in the following. Positive amplifiers are Binding, Curiosity, and Assertion.

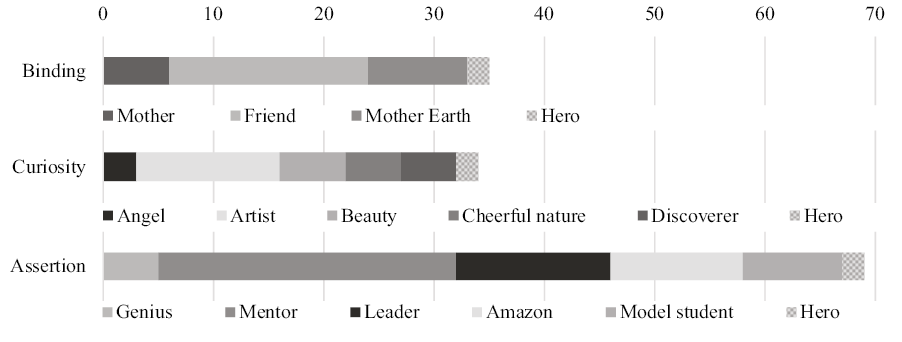

The relation of motivational systems, amplifiers, and archetypes is shown in Figure 1 by the example of the motivational system Autonomy.

Figure 1. Relation of motivational system, amplifiers, and archetypes by the example of the motivational system Autonomy (Own representation)

Table 1 presents the archetypes and positive amplifiers according to Pätzmann and Hartwig and the motivational systems according to Bischof (Jung, 1968; Pätzmann and Adamczyk, 2020).

Methodology

The selection of the 50 largest German construction companies was based on a company list from July 2021, compiled by the Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie e.V., (2021) (Main association of the German construction industry). The data collection of this study focused on online research of both company websites and company pages on the social networks LinkedIn and Xing, of the 50 largest German construction companies. In addition to the straplines, information about the active sub-branches, the range of services, and the predominant type of business relationships were identified via the mentioned websites. The research can be divided into the following three steps:

1. Analysis of the mentioned websites

2. Assignment of the archetypes based on the company straplines (research method: content analysis)

3. Derivation of the predominant archetypes, the human motivational systems, and the amplifier

Analysis

Table 2 presents the identified straplines for each company. Four companies for which no clear company strapline was identified are not included in the further exploration.

In practice, companies combine several archetypes when creating brand personalities and brand values to create a character that is as specific and suitable as possible (Pätzmann and Hartwig, 2018). For example, the strapline of the Thomas Group ‘With passion into a secure future’ (ger. ‘Mit Leidenschaft in eine sichere Zukunft’) (Thomas Beteiligungen GmbH, 2022) trivially contains per definition the two amplifiers Curiosity and Binding with the characteristics of the archetypes Beauty and Mother (see Table 1). In this study, three different archetypes from Table 1 were assigned to each company strapline within a three-step procedure.

1. In the first step, the lexemes of the defined adjectives per archetype were compared with the individual company strapline. If correlations were detected, the corresponding archetypes were assigned to the strapline. For example, the company Berger Group with the strapline ‘Developing an innovative and creative future (ger. ‘Zukunft innovativ und kreativ erschließen’) was assigned the archetype Artist, since the term ‘creative’ corresponds to a characteristic of the archetype Artist.

2. Further research was carried out to find synonyms for the individual terms of the strapline. For example, Wolff & Müller’s strapline ‘Building with excitement’ (ger. ‘Bauen mit Begeisterung.’), was assigned to the archetype Model student since the term ‘excitement’ is synonymous with the characteristic ‘enthusiastic’.

3. If less than three different archetypes could be assigned with the first two steps, the strapline was considered as a whole, and an adjective was assigned that was most similar to the strapline or a part of it. For example, the strapline ‘Planning. Building. Management.’ (ger. ‘Planen. Bauen. Betreiben.’) of ZECH Group was assigned to the archetype Amazon. The three terms of the strapline symbolise that the complete life cycle of a building is covered by the company as a service, which is aptly reflected by the Amazon characteristics ‘independent’, ‘sovereign’ and ‘powerful’.

Table 3 shows the allocated archetypes for each construction company.

Results

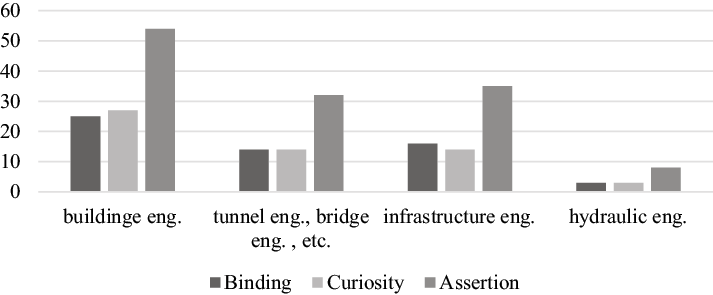

As described in Table 2, no clear company strapline can be assigned to four companies. With the resulting 46 analysed company straplines, the total number of assigned archetypes is 138 (3 archetypes multiplicated with 46 company straplines). Figure 2 shows the archetypes according to the number of times they were classified per amplifier. According to Pätzmann and Hartwig (2018), the archetype Hero has a special role because, unlike the other archetypes, it can be assigned equally to all three amplifiers. To ensure a percentage comparison between the amplifiers, the total number of the archetype Hero was divided between the three amplifiers.

Figure 2. Number of mentions for the amplifiers and each archetype

As Figure 2 shows, the archetypes of the amplifier Assertion are predominant with about 50% (67 mentions) which derives finding A. The archetypes of the amplifier Binding were assigned 33 times and those of the amplifier Curiosity 32 times.

The archetype Mentor of the amplifier Assertion was assigned 27 times and thus with more than half of the company straplines (finding B). The archetypes Friend (18 mentions; Amplifier Bonding) and Artist (13 mentions; Amplifier Curiosity) represent the predominant archetypes of the other two amplifiers. It is notable that the other archetypes (Leader: 14 mentions and Amazon: 12 mentions), which have more than ten mentions, are assigned to the amplifier Assertion.

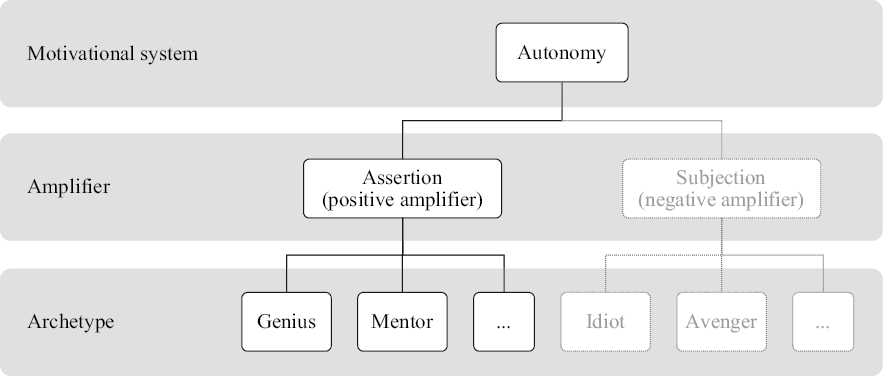

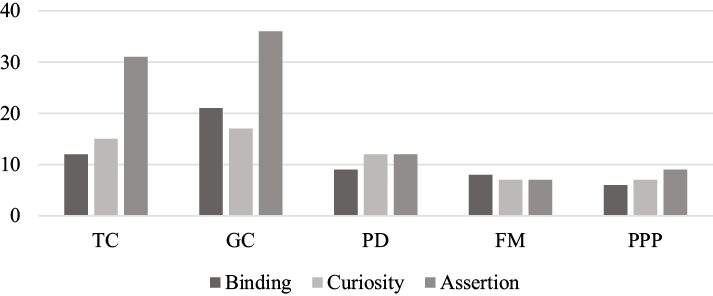

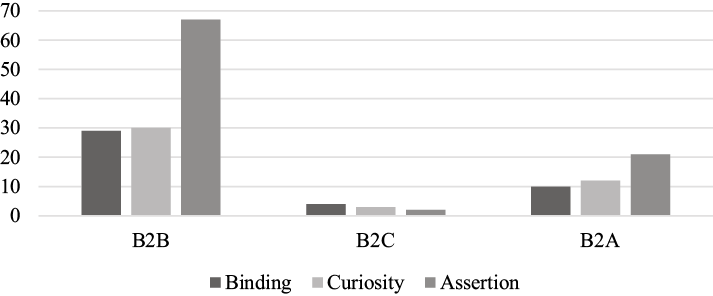

Next to the straplines, the sub-sectors, the service ranges, and the types of customers were identified. The companies can be subdivided into the sub-sectors of building engineering, tunnel/bridge/etc. engineering, infrastructural engineering, and hydraulic engineering. Most of the companies operate in the field of building engineering. It is also evident that most companies are not only active in one sub-sector. Likewise, a breakdown can be made according to the scope of services provided by total contractors (TC), general contractors (GC), project developers (PD), facility managers (FM), and public-private partnerships (PPP), as well as according to the business-to-business (B2B), business-to-customer (B2C) and business-to-administration (B2A) relationships. The predominant services performed by the companies are both total and general contractor services. The dominant type of business relationships is B2B. Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the respective breakdown according to the three amplifiers.

Figure 3. Differences in the sub-sectors

Figure 4. Differences in the scope of services provided

Figure 5. Differences in the business relationships

In each sub-sector, the amplifier Assertion is consistently the most strongly represented. In all sub-sectors, the amplifiers Binding, and Curiosity are almost consistently exceeded by 100%. This confirms the previously mentioned finding A and shows that there are no significant differences within the individual sub-sectors.

According to Figure 4, for construction companies that offer total contractor services, the amplifier Assertion predominates. For companies that are general contractors, this amplifier is just as predominant. It must be annotated that for companies with services in project development, facility management, and PPP the amplifier Binding and Curiosity play a more significant role.

The classification according to business relationships shows clear differences. The dominance of the amplifier Assertion is particularly significant in companies with B2B relationships. The dominance is reduced for companies with B2A relationships. In the case of B2C relationships, the amplifier Binding is predominant, followed by the amplifier Curiosity.

The following further findings can be derived from the different classifications of the archetypes:

A) In total, Assertion is the predominant amplifier.

B) In total, Mentor is the predominant archetype.

C) Assertion is not predominating within services that are dependent on customer binding.

D) Assertion is not predominating within B2C relationships

Discussion

The four findings (A-D) show that the amplifier Assertion has great significance within the construction industry. In addition, the image of construction companies is very much shaped by the characteristics of the archetype Mentor. The individual findings can be substantiated as follows.

A) In total, Assertion is the predominant amplifier.

Archetypes are used to arouse specific emotions in customers due to their characteristics. The study shows that construction companies most often use the amplifier Assertion. Thereby, a feeling of competence and strength is created, which can be described by the expression of influence and authority (Pätzmann and Genrich, 2020). This is also shown by the fact that construction companies attach great importance to reference projects during tendering. Furthermore, the finding reflects the high significance of monetary decision-making reasons, e.g., in the tender negotiation since this competition is predominantly made through strength and authority. The construction industry, and in particular the building engineering sector, is a polypolistic market in which the price is determined by the supply and demand of many buyers and sellers. The number of demanders in the sub-sectors of tunnel/bridge/etc. engineering is slightly lower, which is defined as a demand oligopoly. However, the increased dominant behaviour to stand out from competitors is consistent in the clarity of the amplifier Assertion (Pätzmann and Hartwig, 2018; Schumann, 2011).

B) In total, Mentor is the predominant archetype.

The archetype Mentor combines the desire to share the wealth of experience and to strive for new knowledge. The Mentor is assigned forward-looking and morally conscious. In the construction industry, the archetype embodies traditional and long-established companies on the one hand. On the other hand, it also illustrates the future orientation that is expressed by new technologies such as Building Information Modelling. The two strengths of the Mentor, experience paired with the visionary view of the future, therefore appropriately reflect the construction companies.

C) Assertion is not predominating within services that are dependent on customer binding.

In contrast to the range of services of general and total contractors, the amplifier Assertion does not predominate in the service spectra of project developers and facility managers, as well as companies active in the PPP projects (see Figure 4). This is because in these sub-sectors the attention of both existing customers and partnerships is of great importance. The services of GC and TC consist mainly of coordinating and realising the construction of planned projects. The services of PD include tasks in early project stages, such as feasibility studies. Since the projects are not fully designed yet, PD services can rather be assigned to the amplifier Curiosity. The services of FM include the administration and management of completed buildings over a period that usually lasts several years. Also, PPP projects last over a long period, which needs stronger customer binding. For both FM and PPP, the pursuit of reliability and long-term commitment can be assigned to the amplifier Binding.

D) Assertion is not predominating within B2C relationships.

In contrast to both B2B and B2A relationships, the amplifier Assertion is not dominant in B2C relationships (see Figure 5). In the construction industry, B2C relationships mainly appear in the sector of residential buildings. A special characteristic of B2C relationships is the high involvement of the customers. In the fulfilment of future plans, such as a homestead, customers deal with the product “building” in-depth whereby the decision-making process can last a long period (Bechler, 2019). Therefore, the reliability, as well as the design and build guarantee provided by the building company, is of great importance, which the archetypes of the amplifier Binding represent. Self-realisation is additionally satisfied with the amplifier Curiosity (Pätzmann and Genrich, 2020). The two amplifiers thus stimulate the customers’ exploratory drive on the one hand and at the same time provide a feeling of comfort and trust on the other hand (Pätzmann and Hartwig, 2018). As a result, the amplifiers Curiosity and Binding dominate in B2C relationships.

Relation between findings and current challenges of the construction industry

The corporate strapline is an important component of corporate communication to convey the brand character to the public (Zerfaß, et al., 2018). An accurate perception of a company strengthens its position in the market (Esch, et al., 2016). However, the straplines of the 46 analysed German construction companies primarily convey feelings of Assertion, such as competence and authority. Moreover, for most of the analysed companies, there is almost no focus on increasingly critical partnership aspects. For those companies that provide services with closer customer contact or those who are active in the B2C business sector, the conveying of partnership awareness is more trivial. Therefore, it is comparatively implemented more strongly.

The current challenges of the construction industry are next to digitalisation and automation, topics around sustainability goals and solutions for the shortage of skilled workers (Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie e.V., 2020; Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie e.V., 2021b). For several years, possible solutions for these challenges were detected in sub-topics such as Lean Construction, Building Information Modelling, or Integrated Project Delivery Models. It has been shown that especially cooperation and collaboration are essential components in all sub-topics. The satisfaction of customer needs constantly counts as an essential target figure, which also intensifies the importance of partnership-based solutions. For example, value creation processes are optimised with the involvement of all participants in the sense of the lean philosophy, Building Information Modelling focuses on a central and common data model, and integrated project delivery models rely on collaborative and transparent project execution.

Straplines are based on a composition of several archetypes to achieve accurate target group-specific communication. This communication can reach a holistic awareness in case the customer’s needs are triggered. However, by analysing the straplines of the German construction industry, it is notable that for the most used amplifier Assertion particularly the partnership approach only plays a minor role. Assertion arouses competence, authority, and strength, which may influence the perception of competitors. However, it could reduce an external effect on potential partners, employees, or customers (Pätzmann and Genrich, 2020). The industry challenges reinforce the need for solid experience paired with the drive for new technologies much more than the single aspect of competence. It is significant that unfortunately 21 of the 46 straplines were not assigned to the archetypes of the amplifier Binding. Thus, a partnership and collaborative awareness of these companies are improbable.

Conclusions

Corporate communication will play an even bigger role in the increasingly digital world and should accurately reflect the value of the company. The analysed straplines should be rethought to adapt to the current challenges of both society and the construction industry. Special attention should be paid to target group analysis to understand the customers’ needs and consequently to obtain the correct external perception of the company. The self-perception must be subordinated to the perception of customers and partners. The company Strabag SE can be mentioned as a positive example. With the change of the strapline in 2014 to ‘Teams work’ Strabag SE (2022), the contemporary and present orientation of the company was taken up in corporate communication. The beneficial and ambiguous effect of the strapline, which can be found in almost every press release and at every construction site, should be emphasised. Thus, it has an above-average level of recognition.

In addition to the recommendation to companies to regularly update the straplines, the study shows that there is also a need for action on the research side. The linking of psychological aspects or the adaptation of psychological models in the construction industry is currently almost non-existent. Likewise, the linking of topics from the field of marketing and the circumstances of the construction industry has hardly been researched. Therefore, interdisciplinary research is necessary to transfer the advantages of psychological approaches or marketing methods to the construction industry. In particular, Carl Gustav Jung´s archetype theory can be applied in various areas and can contribute to the success of a company. Based on this study, it is necessary to uncover intercultural aspects and differences between individual countries. An equally interesting study could explore what adjustments need to be made by companies that operate internationally. Another scarcely researched area is the investigation of the customer side and the discovery of recurring patterns among customers. Here it is particularly interesting to see whether there are dependencies between individual needs and the present characteristics of the customer. As mentioned in the introduction, the conducted study is an essential basis for further research, for example in the area of employee acquisition. In the next step, it would be necessary to analyse the straplines in terms of their attractiveness for potential new employees. The goal should be to develop a holistic concept with which customers and potential employees can be enthused in the long term through corporate communication.

Acknowledgements

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

Arditi, D., Polat, G. and Makinde, S.A., 2008. Marketing practices of U.S. contractors. Journal of Management in Engineering, [e-journal] 24(4), pp.255–64. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(2008)24:4(255)

Bahr, M. and Laszig, L., 2021. Productivity development in the construction industry and human capital: A literature review. Civil Engineering and Urban Planning, [e-journal] 8(1), pp.1-15. https://doi:10.5121/civej.2021.8101

Balmer, H.H., 1972. Die Archetypentheorie von C. G. Jung: Eine Kritik, 1st ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-65370-4_1

Bechler, G., 2019. Nachfrageorientierte Produktlinienoptimierung: Der Einfluss von Präferenzen für Kompromissalternativen, 1st ed. Wiesbaden Heidelberg: Springer Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-25542-8_1

Berndt, R., 2005. Marketingstrategie und Marketingpolitik, 4th ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Strabag SE, 2022. Teams. Nr. 01 2014 Das Magazin der Strabag SE. [online] Available at: https://www.strabag.com/databases/internet/_public/files.nsf/SearchView/55B1E600795E6146C1257EEC00548265/$File/STRA_01_14_teams_final_dt_STRANET_r12.pdf?OpenElement [Accessed 28 January 2022].

Bischof, N., 2020. Das Rätsel Ödipus: Die biologischen Wurzeln des Urkonfliktes von Intimität und Autonomie. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.30820/9783837976595

Brucker Juricic, B., Galic, M. and Marenjak, S., 2021. Review of the Construction Labour Demand and Shortages in the EU. Buildings, [e-journal] 11(1), pp.1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11010017

Cambridge University Press, 2022. Cambridge Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/product [Accessed 28 January 2022].

Dikmen, I., Talat Birgonul, M. and Ozcenk, I., 2005. Marketing orientation in construction firms: Evidence from Turkish contractors. Building and Environment, [e-journal] 40(2), pp.257–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.07.009

Drugova, E.S., Zhelnovakova, M.F., Pomuleva1, Y.A. and Kazorina1, A.V., 2021. Specifics of advertising communication in the construction sector: features, ways to attract attention and directions of functioning. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 751(1):012142. Irkutsk, Russian Federation, 4 December 2020. Bristol: IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/751/1/012142

Esch, F.-R., Klein, J.F., Knörle, C. and Schmitt, M., 2016. Strategie und Steuerung des Customer Touchpoint Management. In: Esch, F.-R., Langner, T. and Bruhn, M., eds. Handbuch Controlling der Kommunikation: Grundlagen – Innovative Ansätze – Praktische Umsetzungen, Springer Reference Wirtschaft. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, pp.329–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-3857-2_15

Gabrielova, K. and Buchko, A.A., 2021. Here comes Generation Z: Millennials as managers. Business Horizons, [e-journal] 64(4), pp. 489-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2021.02.013

Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie e.V., 2020. Bauen statt streiten – Partnerschaftsmodelle am Bau. [online] Available at: https://www.bauindustrie.de/themen/news-detail/bauen-statt-streiten-partnerschaftsmodelle-am-bau [Accessed 28 January 2022].

Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie e.V., 2021a. Die 50 größten Bauunternehmen. [online] Available at: https://www.bauindustrie.de/zahlen-fakten/die-50-groessten-bauunternehmen [Accessed 28 January 2022].

Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie e.V., 2021b. BI trifft am Nachmittag: Mittelstand im Austausch mit der Politik. [online] Available at: https://www.bauindustrie.de/themen/news-detail/bi-trifft-am-nachmittag-mittelstand-im-austausch-mit-der-politik [Accessed 28 January 2022].

Holzhey-Kunz, A., 2002. Das Subjekt in der Archetypenlehre C.G. Jungs. Analytical Psychology [e-journal] 33, pp.159–74. https://doi.org/10.1159/000064895

Jaguar Land Rover Limited, 2022. Our Vehicles. [online] Available at: https://www.landrover.co.uk/index.html [Accessed 28 January 2022].

Jung, C.G., 1968. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated from German by R.F.C. Hull. London: Routledge.

Leslie, B., Anderson, C., Bickham, C., Horman, J., Overly, A., Gentry, C., Callahan, C. and King, J., 2021. Generation Z Perceptions of a Positive Workplace Environment. Employee Responsibility and Rights Journal, [e-journal] 33, pp.171–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-021-09366-2

Mark, M. and Pearson, C.S., 2001. The Hero and the Outlaw: Building Extraordinary Brands Through the Power of Archetypes. New York: McGraw Hill Book Co.

Miscenko, D. and Day, D.V., 2015. Identity and identification at work. Organizational Psychology Review, [e-journal] 6(3) pp.215–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386615584009

Mokhtariani, M., Sebt, M.H. and Davoudpour, H., 2017. Construction Marketing: Developing a Reference Framework. Advances in Civil Engineering, [e-journal] 2017, pp.1-14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7548905

Pätzmann, J.U. and Adamczyk, Y., 2020. Customer Insights mit Archetypen: Wie Sie mit archetypischen Metaphern Zielgruppen besser definieren und verstehen können, 1st ed. Wiesbaden Heidelberg: Springer Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-30748-6_1

Pätzmann, J.U. and Genrich, R., 2020. Employer Branding mit Archetypen: Der archetypische Persönlichkeitstest zum Finden von markenkonformen Mitarbeitern, 1st ed. Wiesbaden Heidelberg: Springer Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-31290-9_1

Pätzmann, J.U. and Hartwig, J., 2018. Markenführung mit Archetypen: Von Helden und Zerstörern: ein neues archetypisches Modell für das Markenmanagement, 1st ed. Wiesbaden Heidelberg: Springer Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-23088-3_1

Polat, G., 2010. Using ANP priorities with goal programming in optimally allocating marketing resources. Construction Innovation, [e-journal] 10(3), pp.346–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/14714171011060114

Polat, G. and Donmez, U., 2010. ANP-based marketing activity selection model for construction companies. Construction Innovation, [e-journal] 10(1), pp.89–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/14714171011017590

Roesler, C. and Vogel, R.T., 2016. Das Archetypenkonzept C. G. Jungs: Theorie, Forschung und Anwendung, 1st ed. W. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer GmbH.

Scheier, C. And Held, D., 2018. Wie Werbung wirkt: Erkenntnisse aus dem Neuromarketing. Freiburg München Stuttgart: Haufe-Lexware. https://doi.org/10.34157/9783648109052

Schneider, M.E., 2001. Motivational Development, Systems Theory of. In: Smelser, N.J. and Baltes, P.B. eds. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Pergamon, Oxford, pp.10120–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01661-2

Schumann, J., 2011. Grundzüge der mikroökonomischen Theorie, 9th ed. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21225-3

Shlepneva, T.O. and Maletina, T.A., 2021. Marketing in construction, as a systematic approach to managing the activities of a construction organization. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 751(1):12176. Irkutsk, Russian Federation, 4 December 2020. Bristol: IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/751/1/012176

SOKA-BAU, 2020. Ausbildungs- und Fachkräftereport der Bauwirtschaft. [online] Available at: https://www.soka-bau.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Dateien/Unternehmen/ausbildungs-und-fachkraeftereport_2020.pdf [Accessed 28 January 2022].

Thomas Beteiligungen GmbH, 2022. thomas gruppe. [online] Available at: https://www.thomas-gruppe.de/ [Accessed 28 Jan 2022].

Welter, R. and Luban, K., 2022. Baubranche – Corona-Krise: Der Anfang vom Ende? In: Luban, K. and Hänggi, R., eds. Erfolgreiche Unternehmensführung durch Resilienzmanagement. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, pp.139–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-64023-4_10

Winkelmann, P., 2012. Marketing und Vertrieb: Fundamente für die Marktorientierte Unternehmensführung, 2nd ed. München: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

Yisa, S.B., Ndekugri, I.E. and Ambrose, B., 1995. Marketing function in U.K. construction contracting and professional firms. Journal of Management in Engineering, [e-journal] 11(4), pp.27–33. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(1995)11:4(27)

Zerfaß, A., Bentele, G., Schwalbach, J. and Sherzada-Rohs, M., 2018. Unternehmenskommunikation aus der Perspektive von Top-Managern und Kommunikatoren. In: Hoffmann, O. and Seidenglanz, R., eds. Allmächtige PR, ohnmächtige PR: Die doppelte Vertrauenskrise der PR. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, pp.197–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-18455-1_9